The jury has always been out on Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920), and probably always will be. His “problem” is that sugary manner of his that turns every woman he paints into a belated Florentine Madonna with an impossibly long neck, an oval face and almond eyes. We can forgive his notorious drinking, his notorious hashish-smoking, his notorious womanising. But the notorious tweeness of his female portraits is an obstacle too many.

Of course, plenty of artists of his era — most artists of his era — were borrowing from “primitive” sources in an attempt to return to a truer art. But where others were stealing grit and truth from African sculpture, Modigliani was stealing sweetness and lies from Botticelli. Hey, Modi, you feel like grumbling, the 15th century is over. That said, I have experienced enough moments of unexpected passion in front of his work to suspect him of a powerful unevenness. Yes, most of the time his art is irritatingly mannered. But occasionally it packs a wallop.

It is in the hope of encountering such a moment that I advise Culture readers never to miss a Modigliani show, even one as seemingly modest as the light sprinkling of his drawings that has arrived at the Estorick Collection. With some artists, the gaps say as much as the solids, and Modigliani is certainly one of those.

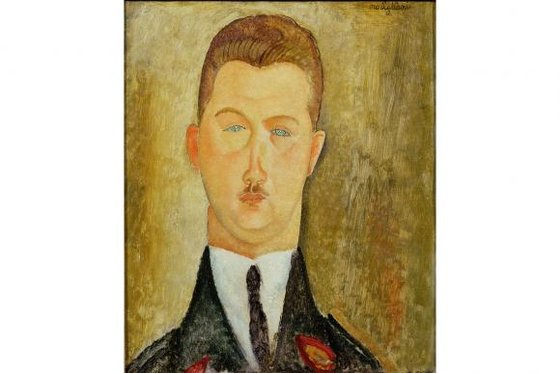

On stepping in, the first impression is: where’s the art? A sparrow walking across a fresh fall of snow would leave deeper tracks than these. He was always a concise draughtsman, but this particular selection seems especially concise. The whiteness, though, is deceptive. What is actually happening in this pale ring of images, mostly of the female nude, is that Modigliani is recurrently searching in them for the perfect outline: the single stroke, in exactly the right place, that best sums up a complex contour. Lots of artists have also searched for perfect contours with thin lines — Picasso in his Vollard years springs immediately to mind, or Hockney in his 1960s portraits. What’s different with Modigliani is that his line has a sense of movement to it, too, like the swish of a swordsman’s blade. This isn’t just precision. It’s precision at speed. It might not always work, but it’s a courageous way to draw and demands true skill.

The current selection is based on a hoard of works from the early days of Modi’s career assembled by the London art dealer Richard Nathanson. In recent years, Nathanson has been seeking in various pronouncements and displays to enlarge the role played in Modigliani’s development by the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

It has long been known that Modigliani and Akhmatova had some kind of relationship. What the relationship consisted of, and what it led to, has remained more mysterious. But the fact that she put a Modigliani drawing of herself on the cover of her momentous final collection, The Flight of Time, published in full at the climax of the Khrushchev years, in 1963, suggests that her dalliance with the handsome Italian had more meaning for her than has previously been accepted. The present selection of drawings argues that the same can be said of him.

They met in 1910, when she came to Paris on her honeymoon. She returned in 1911, having left her new Russian husband behind in St Petersburg. Make of that what you will. Some say it was merely a meeting of minds: two poetic sensibilities colliding. But knowing Modigliani as we do, we should surely suspect a whole lot more than that. The way he draws the curves of her bottom, or the fuss he makes over the nape of her neck, are not insights you gain from a meeting of minds.

As well as being a giant of a poet (“You will hear thunder and remember me, And think: she wanted storms…”), Akhmatova was also a fabulous-looking woman. 5ft 11in. Willowy. Oval-faced. Black-haired. Sharply cheekboned. Having fixed her in our thoughts, the Estorick show encourages us to play Spot the Akhmatova as we pass from delicate, oval-faced, archetypal Modigliani nude to delicate, oval-faced, archetypal Modigliani nude. Is she there in all of them?

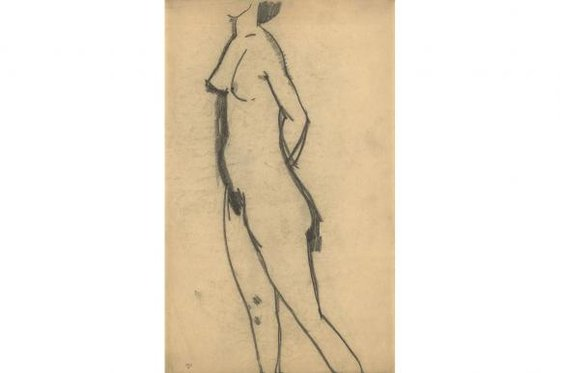

She was certainly the model for the lovely 1911 drawing known as Kneeling Blue Caryatid. That’s her hairstyle, and that’s her bendiness. Working with blue crayon — unusual in everyone except Modigliani — he has a few simultaneous stabs at getting her elongated outline right, then finally finds it. She is also the model for the drawing known as Standing Nude in Profile with Lighted Candle, in which the flickering candle and flickering nude engage in an exquisite minimalist battle to see who is thinner and more upright.

We know from her published memories that he took her repeatedly to the Egyptian galleries at the Louvre, where he would point out the similarities between Old Kingdom Egyptian queens and her. She became his Nefertiti, his Amarna Princess, and the point this modest display seeks repeatedly to make is that it was Akhmatova’s fusion with the hieratical female shapes of ancient Egypt, rather than the influence of Botticelli or Cycladic sculpture, that inspired the elongated and oval-faced look he favoured in his women. Once she had imprinted herself on his imagination, he could never erase her.

These are interesting ideas. As well as prompting a welcome revisit to the superb poetry of Akhmatova — “I taught myself to live simply and wisely, / to look at the sky and pray to God, / and to wander long before evening / to tire my superfluous worries” — they add weight and seriousness to Modigliani’s image of womanhood.

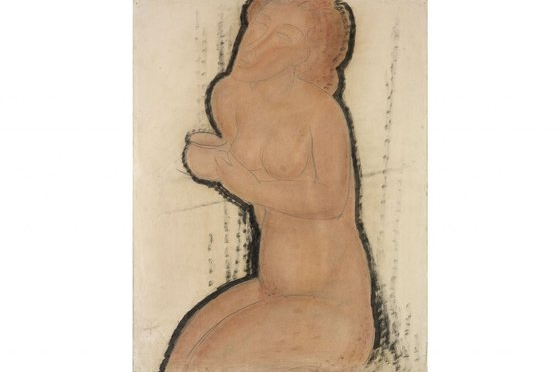

Having established her early influence on his art, the petite two-room show goes on to present us with a whistle-stop tour of Modigliani’s later work. Nude with Cup (c1916) is a big and beautiful drawing in which the image of the kneeling woman is traced with delicate pencil marks on a bed of pink watercolour, then surrounded with a thick blur of black ink, as if she were an island and this was her coastline. It’s a spectacularly original way of drawing. Yet the resulting image is so graceful. Caryatid, also from c1916, pulls off the same effect with a green outline. In this case, the catalogue points out, it was Michelangelo’s Dying Slave, also on show at the Louvre, that was the inspiration for the island nude’s complicated twist one way then the other.

Up on the walls, a helpful quote — “What I was searching for is neither the real nor the unreal, but the subconscious, the mystery of what is instinctive in the human race” — seeks to shed more light still on the origins of Modigliani’s archetypal women. It also begs important questions. Was he attracted to Akhmatova because she already existed in his imagination as an archetype? Or did the archetype come into being because of her impact on him?

Either way, a small show is prompting big ideas.

Modigliani: A Unique Artistic Voice, Estorick Collection, London N1, until June 28