Thomas Struth, whose work is on show in a beautiful and rousing exhibition at the Marian Goodman Gallery, has been one of the instigators of a crucial transformation in photography. Although it has been around for several centuries as an artistic medium, only in the past couple of decades has photography turned into a medium that fills your senses, blots out the background and enfolds you. Having previously been a medium for short stories, it has now become a medium for epics.

The reasons for this excellent development are mostly technical. It wasn’t until colour printing became possible on large-enough sheets of paper that photographs could stop being small and fascinating and acquired a presence that was big, sensuous, colourful and emotive. This change in scale has been critical. It has meant that photography can now have the kind of impact on your senses that had previously been the preserve of painting. And that is what we see here: a photographer who thinks like a painter.

The show features four of painting’s traditional genres — landscapes, portraits, interiors and still lifes — reimagined as photographic disciplines in a display set mostly in that hell’s kitchen of a location formerly known as the Holy Land. Or as we call it today, Israel. Or as the Romans named it, Syria Palaestina. Or as the Umayyad caliphs had it, Jund Filastin. Or as the Roadmap termed it, the State of Palestine. Whatever you call it, it has been the scene of eight millenniums of strife and squabble, and any event set here has its work cut out avoiding a sense of conflict.

Struth, though, manages it. He has always been a finder of balances rather than a recorder of strife. And on walking into this impressive arrangement, set sparsely and elegantly in the roomy white canyons of the Marian Goodman Gallery, the first impressions are unexpectedly light and airy.

Though various painterly genres are being reimagined here, it’s the landscapes that set the tone. If you’ve been to the Holy Land, you will know already that the skies in these parts have a striking glow to them. It’s as if God, in an effort to make Bethlehem stand out, pinned the heavens of Palestine against a light box. In truth, it’s just an accident of geography and colour as a particularly blue sky is contrasted with a particularly chalky ground. But the effect is powerful, and it gives the Holy Land a mythic look.

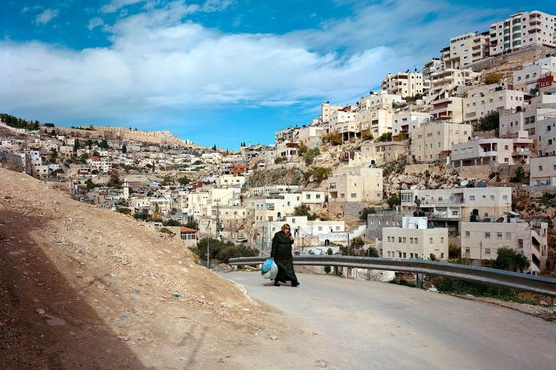

Just such a sky rises up above the exhibition’s signature image, a photograph of Silwan, in East Jerusalem, taken in 2009. It shows two slopes descending into a valley along which runs a dusty road. The slope on the left is barren and dry. The one on the right is busy and crowded, with a cascade of tiny houses clinging to its rocks, as if a fly-tipper has emptied a sack of cubes onto a hillside. Striding up the road between the two symbolic slopes is the striking black silhouette of a Palestinian woman.

Written down, it may not sound like much. But in the photograph itself, looming up before you in vivid widescreen, the effect is huge. Who is this mysterious black figure? Where does the road lead? Why is she walking along it? It’s as if a movie’s worth of possibilities have been squeezed into a single film still.

Struth, who was born in West Germany in 1954, is part of an important group of German photographers who studied at the Dusseldorf Academy in the 1970s — the others included Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff and Candida Höfer. In all of their outputs, the change in photography’s scale has led to a switching of roles. When photographs were A4-sized, we loomed over them. Now the damn things loom over us.

In this particular sequence, Struth seems most often to be noticing how the landscape has been shaped by a struggle much more ancient than the current one between Jews and Palestinians — the struggle between man and nature. It’s most evident in his view of the Shuafat Refugee Camp, also from 2009. The top half of the picture is filled once again with a crowd of those tiny cubistic houses that look like rocks. While the bottom half is once again empty, barren and rocky. Separating the two with a precision that belongs in a graph, not a landscape, is a sinister concrete wall that stretches from one edge of the picture to the other.

Struth’s own name for this land of many names is “The Place”. That’s the title shared by all his pictures of the Holy Land. He first voyaged there in 2009, when he was invited to take part in a mixed show in Tel Aviv. Since then he has been back half a dozen times, working in both Israeli and Palestinian territories, recurrently noticing this same intractable conflict between man’s handiwork and nature’s. An eagle’s nest in the Golan Heights is actually the remains of a lofty gun position. A mountainscape in Nazareth ends its descent on a heap of settlers’ junk.

Although it’s the landscapes that set the biblical tone for this powerful set of images, the interiors, too, have an epic weight to them that had me looking up passages in the Book of Judges. From a distance, the broken columns photographed in Hushniya in 2011 could pass for the remains of the temple knocked down by Samson in his famous battle against the Philistines. Only when you get closer do you recognise a ruined car park in the Golan Heights.

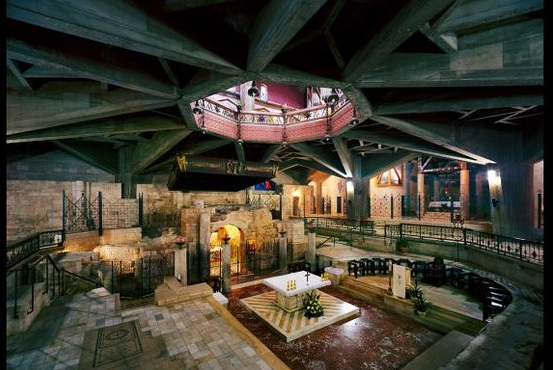

As I said, many of Struth’s ambitions seem conspicuously painterly, and that’s especially true of the superb interior of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, taken in 2011. Looming and sublime, empty of everything except a powerful sense of emptiness, it’s an image Turner himself might have taken if print sizes were as big then as they are now.

Although there is only one portrait in the show, it’s an especially good one. Taking his cue once again from painters — 17th-century Dutch painters of group portraits spring immediately to mind — Struth has posed the Faez family from Rehovot on the stairs outside their home in such a way that all nine members of the family make an individual mark. The dad stares out at us with confrontational fierceness. The mum seeks to look cheerful with a welcoming smile. The daughter on the left has plastered herself with make-up in an effort to look more western. The complex dynamics of the complex lifetime of a complex family have been successfully frozen in a single image.

All this is excellent. Only when it gets to the still lifes does the event take a wrong turn. Photographed in scientific establishments in California as well as Israel, the still lifes feature messy clusters of machinery and wiring that look much too chaotic to be successfully scientific. It’s a paradox worth noting. But not in a show filled as strongly with the flavours of the Holy Land as this one.

Thomas Struth, at the Marian Goodman Gallery, London W1, until June 6