There’s a trend picking up speed in the exhibition world of focusing not on artists but on middlemen. Last year, Tate Britain decided to give us a show devoted to Kenneth Clark, the TV personality and former director of the National Gallery. Documenta, that huge curatorial love-in that holds up the truest of all pictures of the state of contemporary art, set out in its last edition specifically to honour the organisers and theoreticians of art, rather than its makers.

This is the backcloth against which we need to view Inventing Impressionism, a tribute to the pioneering French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, which has set up shop in the cramped basements of the National Gallery. As you go into the foyer, a noisy slab of exhibition hyperbole on the wall shouts out that Durand-Ruel was The Man Who Sold a Thousand Monets. The display that follows counts up everything else he did.

Durand-Ruel, born in 1831, came from a family of art dealers. What made him different when he took over the family business in 1865 was that he was, initially, a risk-taker. The first objects of his support were the fresh-air painters of the Barbizon School — Millet, Rousseau — and an assortment of square pegs who didn’t quite fit the French salon system — Delacroix, Courbet, Corot. The show whisks them all before us, as briefly as it can manage, one picture each if they’re lucky, before settling down to luxuriate over the part of Durand-Ruel’s story that it has really brought us here to celebrate: his relationship with the impressionists.

Just how intimate that relationship was is made clear by an opening room that seeks to feel like Durand-Ruel’s sitting room. A spectacular painted door, filled with Monet flowers, is the actual door from Durand-Ruel’s apartment. Above the mantelpiece, that’s a Rodin sculpture. As for all the Renoirs that surround you — the portraits of various members of Durand-Ruel’s family — those are his own Renoirs. Like all the best art dealers, he took his work home.

It was the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, and the subsequent occupation of Paris by the Germans, that brought him into contact with the impressionists. He actually met Monet and Pissarro in London, where they had fled to safety with their families. The paintings that illustrate this part of the story — Pissarro’s snowy view of Fox Hill in Norwood, Monet’s foggy Thames at Westminster — have an aesthetic softness to them, a sense of holding back, as if being a revolutionary in Sydenham didn’t feel quite as right as being a revolutionary in Montmartre.

Through Monet and Pissarro, he met Manet, who had stayed in Paris to taunt the Germans, just as Picasso was to do in the Second World War (that’s geniuses for you). And in the show’s most startling moment, we hear how Durand-Ruel, encountering Manet for the first time, bought 23 paintings by him in a month. An exciting selection of these, ranging from a fabulous slab of salmon on a lunch table, to a poignant portrait of Manet’s son dressed as a 17th-century swordsman, whose sword is too big for him, caused my tongue to slap against the NG floor with moist desire. All this in a month?

From here on, the show is essentially an excuse to bring us the finest selection of impressionist paintings to arrive in London for years. In his new role as supporter in chief of the movement, Durand-Ruel began buying their work in bulk, paying off their debts, whipping up discussion about them, letting them mount their exhibitions in his gallery and, in essence, allowing them to happen. As a contribution to art history, it was incalculably important.

His particular favourite, Renoir, is particularly well represented. Yes, Renoir can be yucky, and yes, having a taste for him is generally a sign of aesthetic weakness, but when he gets it right, as he does here in three gloriously uplifting dance scenes, his art buffets you with pleasure. Oh, to be on that dancefloor with that girl in that dress in that light, listening to that music. With Renoir, it usually pays to ignore the subject entirely and look only at the brushstrokes. That’s where the revolution happens, in the glowing, shifting, darting brilliance of his touches.

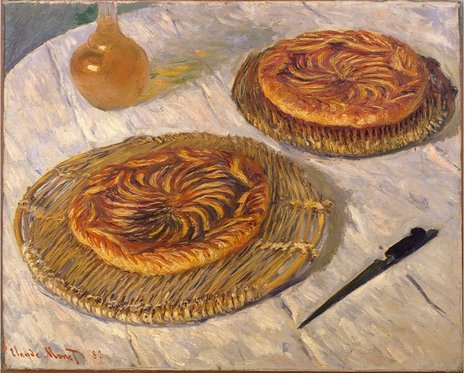

The other exhibition favourite, Monet, is harder to follow. Durand-Ruel collected him in all his phases, and the resulting sense of him is bitty. Early Monet makes something cold and solid of the bleak Normandy coast at Sainte-Adresse, while late Monet causes a row of summer poplars to shimmer intangibly like a mirage. In between, he out-Van-Goghs Van Gogh with a dizzy look-down at some cosmic galettes, the popular French cakes that look here as if they are describing the swirling of the solar system.

In his exhibitions devoted to Monet, mini-retrospectives in essence, Durand-Ruel, we are told, invented the one-man show. He also invented the private view, the supply of reproductions to the press, the manipulation of newspaper coverage, the whole shebang. Before him, the art world operated one way; after him, it operated another way.

The National Gallery doesn’t do psychology, so the reasons for this exceptional support for the wildest artists in Paris remains unexplored. But I’m not bound by the same exhibition rules so allow me a moment’s speculation. Having taken over his father’s business at an unusually young age, his early thirties, Durand-Ruel was old enough to know how the market operated, but young enough to be cocky and to wish to make his own mark. The fact that his own rebellion against paternal values coincided with that of the impressionists is one of those beautiful art coincidences that happen so rarely. His own taste, as evidenced by all those Renoirs, was more conservative. But he knew enough about art to know that it needs to be given its head and, crucially, was brave enough to put his money where his mouth was.

That’s why he’s so different from today’s middlemen, otherwise known as curators, who operate entirely with other people’s money, and who, therefore, will never rock a boat or point themselves in an opposite direction.

Inventing Impressionism, National Gallery, London WC2, until May 31