Among the true greats of art, the top-tenners, there is usually some bleakness sulking in the shadows. Picasso, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Manet were all tragedians who occasionally smiled. The bleakest of the giants, however, the one who saw the least to celebrate in the human condition and the most to despise, was Goya.

The more I see of his work, the surer I am that he hated the rest of us with unbalanced certainty. It’s a good job he was a pictorial genius, and that the brush and the burin were his weapons, otherwise he might have run around late-18th-century Spain shooting people and knifing them. His art has about it an air of unhinged revenge, of excessively fierce cultural payback, as if he had appointed himself society’s judge and jury. At the beginning of his career, there were pleasant rococo clearings in the forest of darkness that is his oeuvre — the early tapestry designs are sweet — but by the end, there were none.

It’s a point made by every Goya display you will attend, but one that is made particularly spikily by the selection of his drawings that has arrived at the Courtauld Gallery, that rare and precious exhibition venue where civilisation clings on by its fingertips. At the Courtauld, you still get shows full of scholarship and care. Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album, as this one is entitled, is a fine example.

Goya kept sketchbooks. Of course, all artists keep sketchbooks, but his were unusual. On every page was a drawing that was carefully captioned and numbered. These, then, were not sketchbooks in which an artist recorded passing sights or worked out brisk compositions. To me, they have about them the air of a comic book, a graphic novel.

Their purpose was surely to prepare the images for a collection of prints he hoped to bring out in the future, like the famous Los Caprichos or the terrifying Disasters of War. Nerdishly, and with mildly unbalanced exactitude, Goya was arranging his psychotic outpourings into a neat and publishable sequence. Unfortunately, when he died, these punchy sketchbooks — there were eight of them — fell into the hands of his ne’er-do-well heirs, who sold them off in parts to pay the bills. Most of the scenes were scattered about the museums of the world, their order and meaning lost for ever. Or so it seemed.

In the old days, the sketchbooks were known by the letters A to H. Today, they have acquired sexier nicknames, and the one under examination at the Courtauld, formerly known as Album D, is now called the Witches and Old Women Album.

Its new legibility is the handiwork of Juliet Wilson-Bareau, doyenne of Goya studies, who has not only identified all the surviving drawings from Album D, but has also had a go at putting them in the right order. It’s the first time anyone has arranged one of Goya’s “graphic novels” in a viewable sequence.

The show actually commences with a context-setting room in which we are introduced to the wider story of the sketchbooks. The Goya presented to us here is immediately fierce and nasty. Under the title The Whole House Is in Uproar Because the Poor Little Bitch Hasn’t Done Her Duty All Day, we see a sobbing prostitute and her wizened procuress crying over the lack of business, while the other “bitch” in the drawing, a dog furiously humping a client’s leg, looks out at us quizzically. Geddit?

Strange how the Gauguins and Picassos of this world are regularly upbraided for their misogyny, while Goya, a much more obvious woman-hater, remains widely unaccused. Once noticed, his bitch-calling and misogyny are spectacularly unrestrained.

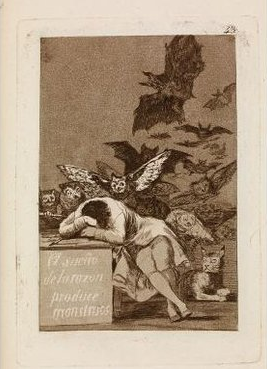

Several superb prints from his graphic masterpiece Los Caprichos, to my eyes the greatest book of prints ever made, complete the scene-setting with a scary fly-past of naked witches and their madly girning victims. Then we’re into sketchbook D, with its bumpy and elusive narrative.

It was apparently drawn in 1819-23, the years when Goya acquired a house outside Madrid and filled it with his notorious Black Paintings. At 50, he had gone deaf. And the horrors of the Napoleonic Wars were still fresh enough in his mind in 1819. The year after the sketchbook was finished, in 1824, he left Spain for France, unable any longer to stomach the state of his homeland. So these were some of his darkest days.

The Witches and Old Women Album is called that because it starts with a set of scenes of assorted human grotesques — old women, prostitutes, monks — falling out of the sky, grinning and grabbing fiendishly. Nothing specific brands them as witches and necromancers, but there’s certainly something wicked about them, and the mood they create is warped and, yes, passably occult.

They actually reminded me of the crazy figures you see descending to hell in the Rubens show currently at the Royal Academy, in the picture known as The Fall of the Damned. These are the wicked — biting, grinning, tugging, pulling and screaming their way into Satan’s hands in a mad waterfall of sin.

Confusingly, the next batch of images in the comic book seems to be set on earth, where a parade of single figures, mostly old women, hobble past us, and scowl as they walk the catwalk of decrepitude. If there’s an ounce of sympathy towards the aged being shown here by Goya, I missed it.

What does it all mean? I have no idea. And neither do the organisers. Somewhere in Goya’s dark imagination, the artistic beating-up of all these old people must once have had a purpose, but that purpose is long gone, and no amount of clever Courtauld scholarship will bring it back. All we’re left with is an explosion of disgust that has been carefully numbered. c

Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album, Courtauld Gallery, WC2, until May 25