Tate Modern does lots of things well, but national commemoration is not generally one of them. They are just too cool over there, too conceptual, too emotionally careful, to tune in properly to a big national mood. In many ways, the spectacular ring of red that surrounded the Tower of London in this year’s most involving art event could have been a Tate gesture. It was abstract. It was monochrome. It was conceptual. But it was also thoroughly emotional, and that is the bit Tate Modern cannot do. It can’t do poppies.

So Conflict, Time, Photography, which has finally tiptoed into the art calendar as part of this year’s national remembrance of war (sort of), is not an event that looks war in the eye. Indeed, the show seeks deliberately to avoid looking war in the eye. Instead, it comes in after the event to examine various postscripts of war: the shadows, the aftershocks, the ruins. It’s an exhibition strategy that seeks, therefore, to view things from a typically Tate-ish conceptual distance. Rather surprisingly, it works.

To pick an obvious example — it’s the first thing you see when you enter — the French photographer Luc Delahaye gives us a stretching landscape, with an unusually bare horizon, above which floats a small grey cloud. That’s all. There’s nothing else in the picture. Only when you read the title — US Bombing on Taliban Positions 2001 — does the empty landscape begin filling out into a dark narrative. That’s not a cloud. It’s the smoke from the bombing. That’s not an empty field. The Taliban are hiding in there somewhere. The great plus of conceptual art — and it’s as true of the field of poppies around the Tower as it is of Delahaye’s lonely cloud — is that all the action, all the meaning, takes place inside the viewer’s head. It’s not the artwork that brings the emotions to the table. It’s you.

On the other side of the room from Delahaye’s empty Afghan landscape, a Japanese photographer called Toshio Fukada shows us the mushroom cloud above Hiroshima, 20 minutes after the explosion of the first nuclear bomb. Fukada was 17 when he took the pictures. He was just a student who ran for his camera. But, like Delahaye’s Afghan landscapes, the resulting close-ups of the mushroom cloud are weirdly beautiful.

These, then, are different outlooks. The show is full of them. Their value is that they expand mightily our understanding of what conflicts actually entail. By not approaching war directly, or predictably, the exhibition shows us things we haven’t seen anywhere else this year.

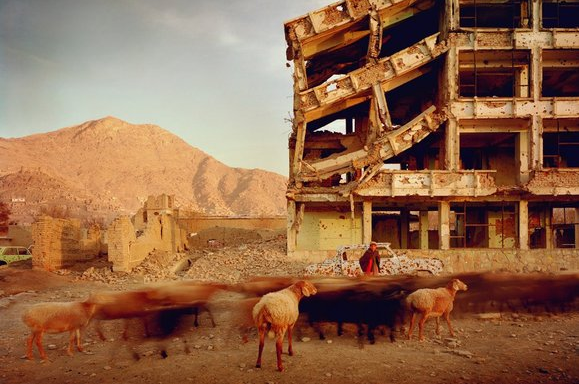

Beauty, the guest nobody ever invites to a war, keeps turning up. In 2001, Simon Norfolk visited Afghanistan during a lull in the fighting and produced a series of stunning “magic hour” photographs of the ruins left behind by successive Afghan conflicts. Some were ancient. Others were freshly made. Some were mosques. Others were Russian observation posts. All of them have a sense of disposability about them when compared with the dusty and worn-out landscape in which they stand. The land, you feel, has seen it all.

None of these photographers actually describes a war. What they all do, instead, is smuggle its problematics into you. Cleverly, the show has arranged their contributions in different time slots to create a narrative that unfolds across the entire show. At one end, Delahaye and Fukada arrive on the scene minutes after the explosion; at the other end, Chloe Dewe Mathews does not track down the sites at which British soldiers accused of cowardice in the First World War were shot until 99 years after the killings. In 2013.

And her locations are such ordinary-looking places. An irrigation ditch in a field. A snowy wood, messy with fallen branches. Knowing what happened in these run-of-the-mill places turbo-charges their ordinariness into an accusatory roar.

Something else the show does really well is vary its moods. War is a million things, not one thing. Norfolk may see picturesque beauty in the golden ruins of Afghanistan, but when Pierre Antony-Thouret began documenting what had happened to his home town, Reims, when the Germans began bombing it in 1914, he found a ruination so complete that it seemed to form a pebbly beach with a rock in the centre. The rock was all that remained of the cathedral.

Antony-Thouret’s pictures are unusual in being able to present destruction as a viewable, graspable entity. With the dropping of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, all such graspability was made impossible. There isn’t a lens in existence wide enough to capture what happened in Japan in 1945. That story can only be told in details.

Thus, the dark circle on the right in Kikuji Kawada’s pictures of Hiroshima shows the crushed remains of a Japanese flag, while the dark circle on the left shows the crushed remains of a Lucky Strike packet. What kind of a god in what kind of a mood arranges for a crushed national flag and a crushed packet of American fags to rhyme so perfectly with each other? A Lucky Strike indeed. Bravo, Tate Modern. Just when we thought we had heard all there was to hear about war this year, you’ve unearthed an engrossing cache of new storylines.

Conflict, Time, Photography, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Mar 15