Having seen Jeremy Deller’s stimulating two-hander, in which William Morris is compared to Andy Warhol, I made the huge mistake of actually reading Love Is Enough, the pseudo-medieval morality play, written by Morris in 1873, that has given Deller’s show its title. Love Is Enough, the exhibition, is provocative and fun. Love Is Enough, the morality play, is twaddle.

It tells the tale of a vaguely medieval king who spends the play worrying about whether he should give up his kingdom for love. Written at a time when Morris’s wife, Jane, was offering too much of herself to that pre-Raphaelite cad Rossetti, it’s an escape into the world of Lancelots and Guineveres so complete that, if I were deciding on the categories, I would file under Unhinged, rather than In Love. Here’s some dialogue:

KING PHARAMOND. We twain were to wend through the wide world together/Seeking my love — O my heart! is she living?

MASTER OLIVER. God wot that she liveth as she hath lived ever.

As I said, nutty, escapist and from a different planet than Warhol. Deller, on ye other hand, sees nothing disqualificatory in Morris’s mad flight from the realities of late-Victorian England. As a former winner of the Turner prize, Deller has placed Morris next to Warhol for two big reasons. First, because the pair have been important influences on his own career. Second, because he sees so much in their respective outputs that can be compared. Warhol from 1960s Manhattan and Morris from Victorian England were, he says, like-minded artists at heart.

The argument, mounted with parallel selections of art and documentary materials, arranged in thematic clusters, begins with a section called Camelot, in which Morris can be seen dreaming of Arthur’s England, just as Warhol dreams of Hollywood. As boys, both of them escaped into faraway worlds inhabited by beautiful people. In Victorian Walthamstow, Morris would ride around his garden on a Shetland pony, dressed in a miniature suit of armour. In 1940s Pittsburgh, Warhol, a sickly child who often missed school, would write to Hollywood stars asking for their autographs. He was particularly pleased to receive a signed picture of Shirley Temple, all golden curls and rosy smiles, dedicated to “Andrew Warhol”. It became a talismanic presence among his possessions.

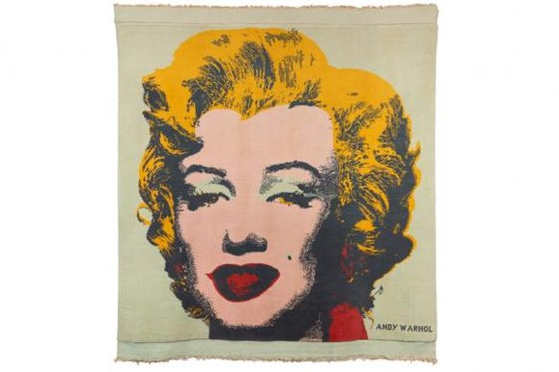

To prove it, Deller has hung a fabulous Marilyn rug, from 1968, next to the Shirley Temple photo, and encouraged us to count the rhymes between the two smiling blondes. I was particularly struck by the way Warhol’s silkscreen effects, with their patches of added colour, were so obviously descended from the colour patches on hand-tinted photographs like the one Shirley sent to Andrew.

Monroe was, of course, involved with John F Kennedy, and Camelot was the nickname given to the “court” of the Kennedys. And, since Warhol was also obsessed with Jackie Kennedy — she appears in no fewer than 300 of his paintings — the show appears to be on firm ground when it compares a huge Burne-Jones tapestry of Sir Galahad searching for the Holy Grail, made by Morris & Co in 1896, with a row of Warholian images of Jackie, Marilyn and John F. The two Camelots look different, goes the show’s argument, but they add up to the same thing.

Unfortunately, they don’t. Where Morris’s dream world is nostalgic and irrelevant, Warhol’s is futuristic and on the button. In Warhol’s Camelot, the smiling Jackies cut out from glamour magazines, the pouting Marilyns and their soap-opera storylines, prefigure inch-perfectly the celebrity culture of today. This is art that is astonishingly prescient. Over in the Morris corner, the ye olde Englande being re-enacted by swooning damsels and jousting knights survives nowhere today except in our nostalgia for the decor of Berni Inns.

The show’s next section, in which Morris’s politics are compared with Warhol’s, is again overly hopeful. Morris’s shouty socialism, brought about by a life-changing confrontation with Karl Marx, found a voice in writings, meetings and street protests. Warhol, meanwhile, although definitely a darker thinker than is usually admitted, was never a naysayer. The two images of electric chairs included here are pessimistic works of art, yes, but they’re not trying to start a revolution. Warhol’s ambition, you feel, was to succeed in the world as it was, not to turn it into somewhere different.

Where the comparison finally becomes convincing is in examining the work practices of the two men — and especially their creation of communal studios. Warhol’s Factory and Morris & Co had much in common. Both men liked to surround themselves with like-minded creatives. Both had a defining faith in the power of art. Neither was afraid of machines, and both sought to give their output as much mechanical help as possible.

They shared an appetite, too, for voyaging merrily across all the arts. Both set up important publishing concerns: Morris with the Kelmscott Press, Warhol with Interview magazine. Both were good at business and unashamed of its role. In short, both were important ancestors of today’s art world. No arguments there.

Until now, the show has been long on documentary evidence, but short on aesthetic joy. The final room, called Flower Power, succeeds, finally, in reversing those impressions by being filled with alternating displays of Morris’s glorious wallpaper and Warhol’s glorious flower paintings.

So. It’s all very stimulating. Deller has created an exhibition that feels spiky and adventurous. Unlike most theme shows forced upon us by contemporary curators, it has a real point to make. The installation is splendid. The catalogue is good. The only big letdown is the art.

Morris, the better represented of the two, with huge tapestries and looming cliffs of wallpaper, is a producer of pseudo-medieval treacle: so dense and sweet and sticky. Warhol, the greater artist by far, has the misfortune to be so commercially valuable now that his important works are impossible to borrow. Worse still, the body that polices access to his work, the Warhol Foundation, is notoriously controlling. How perverse that an artist whose greatness was based largely on the appropriation and enhancement of other people’s images should be represented today by a body as imagistically ungenerous. Fie upon them, as one of Morris’s Lancelots might put it.

Love Is Enough, Modern Art Oxford, until Mar 8