As soon as I stepped into the Joseph Kosuth show at Sprüth Magers, I began to think about how art operates. What it does. Where it does it. Kosuth, I should add, by way of explanation, is one of the world’s most venerable conceptual artists. He might even be the most venerable. In 1968, when he was 23, he was chosen as the winner of the Cassandra Foundation Grant by — wait for it — Marcel Duchamp. A week later, Duchamp was dead. So we are talking here about a line of succession.

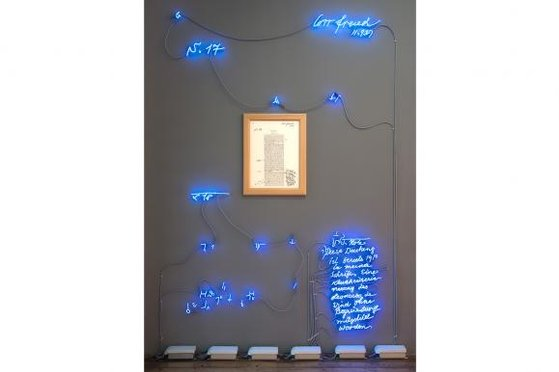

The Sprüth Magers show presents a selection of neon works, from 1965 to the present, and features assorted words and signs, drawn from various sources, appended to the walls in glowing neon clusters. One of them enlarges a set of handwritten corrections made by Sigmund Freud to his essay Fetischismus. Another compares a line of music from a Rossini opera with the matching line of the libretto. My Italian is rusty. My German is rusty. Neither the Rossini neon nor the Freud one meant anything obvious to me. Yet I found myself enjoying both of them. Why was that? Hmm. As I said, as soon as I walked in, I began to think about how art operates.

One of art’s best qualities is its untameability: its refusal to sit when you shout “Sit!” It’s not a science. It’s not a skill. It’s a poetic force that slips the leash of reason to have its say. Perversely, bad artists are more successful than good artists at keeping the beastie quiet. If you’re a bad artist — a Dufy, a Vettriano — you leave art no room in which to operate. If you’re a great artist — a Picasso, a Rembrandt — you leave it lots of room. So much, you are basically setting it free. A great Rembrandt self-portrait is so full of interpretive opportunity that your thoughts rush in like a tsunami to fill the gaps.

Kosuth’s art is all gaps. Some of the people he is quoting around the walls of the gallery are philosophers I have little time for. Adorno, I have previously found, is a helpful mentor only when you cannot sleep. Even Freud is of no realistic consequence when he writes in German about fetishism. So what’s working here isn’t the words or the neon. What’s working is what happens when one iscombined with the other. Art, you see, is a chemical reaction that involves no chemicals. Tah dah.

Kosuth began working with neon in 1965. That’s early. Indeed, it’s pioneering. These days, we are used to seeing neon being used as an artistic material. No Tracey Emin show would be complete without it. But it was Kosuth who first noticed that there is something different about words written out in neon — something transformative and mysterious.

The earliest work in this show dates from 1965 and is called Five Fives (to Donald Judd). It consists of five rows of orange neon counting out numbers, not in digits, but in letters. The first row counts from one to five. The second row counts from six to ten. And so on. Until we get to 25 — five fives.

As the numbers grow higher, so the words and the rows get longer. Until, finally, they form a stack, with the longest lines of neon at the bottom and the shortest at the top. And that’s where Donald Judd comes in.

Judd was a marvellous minimalist sculptor, best known for working with coloured boxes of different sizes. So Kosuth’s stack of differently sized neon rows has something suggestively Juddish about it. Nothing obvious. It’s all whispers and butterfly touches. But it’s definitely there. Because art is sometimes a cake, but other times it’s a sorbet. Tah dah.

The show has been beautifully installed against grey walls that seem to give the neon extra wattage. Neon appealed to Kosuth, he has explained, because of its lowly origins. In 1950s America, it lured you into strip joints and hamburger bars. It was the messaging system of the streets: unimpeachably common. Yet put it in a gallery, take it out of the night, switch off its siren call, and you have a fabulously effective artistic material.

All lights glow, but neon glows with a throbbing halo that seems to single out the words and signs. As you know, I can be foolishly art historical at times and completely lose my sense of perspective, so as I stared at one of Kosuth’s many tributes to Samuel Beckett, I found myself remembering the mystical visions of St Bridget of Sweden, who saw the baby Jesus glowing in the manger, emitting his own light: it’s why so many Renaissance nativities show Jesus glowing like a neon sign. More sensible readers may wish to remember Wurlitzers rather than Christs, and to enjoy neon’s gorgeous throbs for straightforward retro reasons.

Kosuth’s treatment of neon is often impish and sometimes brilliant. He uses it in unexpected ways: to evoke Freud; to consider Beckett; to confront us with mysterious algebraic calculations. Neon, a material you expect to be quoting Raymond Chandler at you (“It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window”), is employed, instead, to encourage you to “imagine light”. Art, you see, is about the gaps as well as the solids. Tah dah.

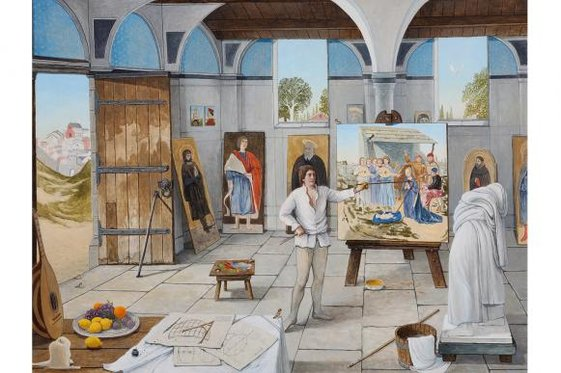

Just around the corner, in the John Martin Gallery, the Scottish painter Barry McGlashan has unveiled a set of less complicated pleasures. McGlashan’s paintings of artists’ studios feature some of art’s bestknown names: Gauguin, Monet, Picasso, Botticelli, Bruegel. All of them can be seen at work on famous pictures in environments imagined for us in hilarious detail.

Thus, Botticelli, at work on his great Primavera, is painting with egg tempera, but the eggs he uses as a binding medium come from two fried eggs instantly reminiscent of Velazquez. Ho ho ho. Monet, the Sisyphus of impressionism, dabs away at one of his giant water lilies with a tiny brush, his poor, cataract-covered eyes just an inch away from the canvas. The water lilies are so big. He’s so small. And I really liked Mark Rothko, sitting there, smoking, in a particularly bare and lofty studio, staring hopelessly at a huge black emptiness. Wait a minute. That’s not a huge black emptiness. That’s his new picture.

Lots of in-jokes then. Lots of ticklish observations about famous artists. But also lots of pathos. Some of the show’s best images have empty canvases at their centre. Like a pause in a Beckett play, an empty canvas can feel so weighty. As I said, in art, the gaps can mean as much as the solids.

Tah bloody dah.

Joseph Kosuth, Sprüth Magers, London W1, until Feb 14; Barry McGlashan, John Martin Gallery, London W1, until Sat