Folk art is the Nigel Farage of the visual arts — beery, boisterous, untutored. If folk art could vote, it would vote to ban Romanians from moving in next door. It’s the voice of the pub, the voice of the country fair, the voice of the Sunday service. As such, it is a voice I never imagined in a million years would one day be heard bawling out the words to Knees up Mother Brown at Tate Britain.

But times change, and so do aesthetic dynamics. The Tate’s celebration of British folk art is actually part of a trend in exhibition-making. Last year’s Venice Biennale was devoted entirely to self-taught artists working outside the official art systems. At the Hayward Gallery, a pioneering display called Alternative Guide to the Universe exposed us, excitingly, to the inner lives of a relentlessly strange assortment of artistic loners and creative obsessives.

The Tate show is part of this trend, but also concerned with something different. Though folk art and outsider art share many features — vitality, unsophistication, inventiveness, a belief in effortful skill — they differ in tone. Folk art isn’t generally interested in private demons and inner worlds. Judging by this delightful and beautifully presented tribute, it is, essentially, a happy language driven by important communal understandings.

When I say the show is beautifully presented, what I chiefly mean is that it is mercifully sparse. Another characteristic folk art generally shares with outsider art is a reluctance to turn off the tap. Most showings of it are crammed to the rafters. This one, to its credit, has been fiercely selective. In half a dozen rooms, carefully colour-coded to guide us through its thematic groupings, British Folk Art takes us on a notably airy journey through the Sherwood Forest of native creativity.

We begin with some shop signs: a lovely golden wall full of giant padlocks, smiling suns, extra-large top hats and extra-extra-large workmen’s boots. Thus the hatters and cobblers of the traditional British high street would advertise their wares to the passing shopper.

The unfeasible size of these hanging adverts is obviously an attempt to make them unmissable. But that doesn’t explain their impish presence. The oversized boots aren’t just large, they are exaggerated and ridiculous, like a clown’s boots. Something more is being expressed here than the need to sell: there is also a desire to entertain your neighbour, crack a joke, share some banter.

Although it spans half a millennium of national creativity, from the 16th century to the 20th, the exhibition ahead feels as if it is examining a mood, not a time scale: an urge, not a style. A pre-industrial society, a world not yet segregated into heartlessly efficient working blocks, is expressing itself in a common artistic language. And most of the time — in the pub signs, the shop notices, the advertising cartoons — it’s a language of fun and cheek and bonhomie.

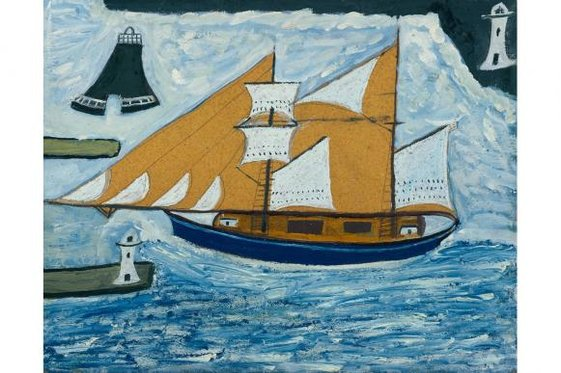

Each thematic cluster focuses on different terrain. There’s a section on lettering; another on landscapes; a third on naval art. This last grouping is the only bit of the show I would have encapsulated further. Once you have seen one wonky Cornish boat painted on driftwood by Alfred Wallis, you really have seen them all.

Elsewhere, it is the variety of the materials and methods used that excites and impresses. Among the early shop signs, there’s a particularly delicate one for Richards, Artist in Hair, which has actually been embroidered from human hair, twisted into flowing scripts and flower patterns with scarcely imaginable skill. A magnificent white cockerel, created by a French prisoner of war during the Napoleonic conflict, has been made from the remains of a penal supper. Every feather is individually carved from leftover beef bones.

Thus, folk art grabs whatever is at hand and transforms it. Humble materials are recurrently turned into precious objects by remarkable displays of perseverance and skill. And these remarkable displays of perseverance and skill seem to say something hugely important about the universal human need for art: the basic level on which it operates.

Interestingly, in one of its first captions, the show reminds us that the Royal Academy specifically forbade “needlework, artificial flowers, cut paper, shell work, or any such baubles” when it was founded. Folk artists were banned from joining. Yet it is precisely because this display shows off so much ingenuity and otherness in the production of art that it appears so vital.

While the paintings of boats are a tad too numerous, the room devoted to ships’ figureheads is eye-poppingly exciting. The wonky painted figures — lions, admirals, goddesses — form such a colourful cast. The mustachioed giant in a turban formerly attached to the front of HMS Calcutta, a Royal Navy vessel in Bombay, was brought back to England by First Sea Lord John “Jacky” Fisher on his retirement from India in 1911. I’m not surprised Jacky Fisher wanted the giant genie in his garden. Like so much folk art, Calcutta has a powerful talismanic presence. You cannot imagine him bringing you anything other than good luck.

A few cabinets earlier, a life-sized straw figure of King Alfred, created in 1961 by the Oxfordshire thatcher Jesse Maycock, has the same weirdly potent symbolic presence. Without knowing how or why, folk art seems instinctively to understand that art’s origins were not in depiction, but in magic.

Several forgotten artists have been highlighted for fresh appreciation. The most remarkable of them is Mary Linwood, a master of Georgian embroidery, whose microscopically detailed re-creations of Old Master paintings are astonishingly skilled. It tells you something significant about the continuing prejudices of art history that Linwood does not appear in any of those laments on forgotten women artists that pop up on the telly or crowd our art bookshelves. She should.

All this adds up to a display of rare vitality. After all the video dirges and hopelessly knotty theorising we have come to expect from shows at Tate Britain, walking in here is like having a glass of fresh water thrown in your face.

British Folk Art, Tate Britain, London SW1, until Aug 31