Back in 1976, an important exhibition called The Human Clay opened at the Hayward Gallery, in London. It was important because it changed things. At the time, abstraction and minimalism were the chosen flavours in art. If you were abstract and minimalist, you were in. If you were figurative, you were out.

The Human Clay begged to differ. Selected by the pop artist Ron Kitaj, the show championed a group of figurative artists based in London, whom it dubbed the School of London. Among them were Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff and Kitaj himself. By pushily grouping and praising them, Kitaj’s show can honestly be said to have redirected the course of British art. I remember it here because the new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, called, pertinently, The Human Factor, has the potential to be viewed in the same way.

This is the most compelling selection of contemporary art I have seen for years. A real sizzler of a show. Soon after I walked in, I wrote down two words in my notes: “visceral” and “witty”. Then I underlined them. Later, I added “impeccably presented”.

The selector, Ralph Rugoff, the Hayward Gallery’s excellent director, is good at finding themes that have real substance. Even his most extreme attempt, an exhibition about the invisible in art, concerned itself with something fully concrete: art’s recurrent desire to confront us with blanks, whitenesses, gaps.

For The Human Factor, he has assembled a marvellous cast of 25 international sculptors who use the human body as their inspiration and playground. One thing art about the body brings immediately to the party is a sense of shared scale. Entering this show is more like joining a carnival procession than visiting a gallery.

In the first vista, an upside-down female ninja hangs from the roof in a death-defying sculpture by Paloma Varga Weisz. Behind her, a pair of wonky wooden giants by Thomas Schütte stand to attention, as if guarding the other exhibits. At the end of the room, what appears to be a caveman with a club steps out in front of an ancient valley, like one of those panoramas you get in natural history museums. Hmmm. Maybe this doesn’t feel like a carnival after all. Maybe it’s more like walking into a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

Close up, the caveman with the club turns out to be an average German tourist in a bearskin. He’s a Flintstone. A falsehood. The show ahead is full of them. The small kneeling figure by Maurizio Cattelan that can only be approached from behind appears to be a little village chappie deep in prayer. So small. So pious. Only when you go round the front do you see he is actually Adolf Hitler.

What’s real and what isn’t? That’s the question the show keeps asking. As the oldest subject in sculpture, the human body ought no longer to be open to those kinds of doubts. But one of the key points being made here, over and over again, is that the authentic and the virtual have grown indistinguishable in the modern world. With pioneering results.

Another of Cattelan’s cheeky installations shows us a body stretched out in a coffin. He, too, looks very real and a bit familiar. But wait. What’s this? He’s dead, right? So why is there an excited bulge in his trousers? Now I recognise him. It’s John F Kennedy.

Cattelan’s naughty leader wind-ups are part of an exhibition-wide investigation of celebrity culture and its attendant reality issues. Cady Noland’s Bluewald features a cutout of Kennedy’s killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, that seems to have been used for target practice. Riddled with bullet holes, an American flag stuffed in his mouth, the Oswald cutout reverses the direction of the Dallas assassination like a magnet switching poles. It is the one that’s been shot. It is the one that’s been silenced.

The show ahead is packed with dummies, mannequins, masks and doppelgängers. The assorted stand-ins usually present modern humanity as something disposable and trite. Thus, in Thomas Hirschhorn’s savage and powerful 4 Women, four sexy shop-window dummies are compared with four corpses photographed in wars. Both the corpses and the dummies are decomposing. But where the corpses in the photos are spilling red blood, the dummies in the vitrines are spilling bright blue polystyrene. In the red corner: the shocking truth. In the blue corner: the shocking fantasy.

Don’t think, though, that it’s all darkness and doom. It isn’t. The single most marvellous thing about this show is how fresh it feels. We might have expected art about the human figure to have said everything there was to say on the subject long ago, but the opposite turns out to be true. The modern world may be trashy and virtual, but that hasn’t stopped it being inspirational. Look how fiercely art has been expanding the range of figure sculpture in recent years, with new materials, new thinking, new irreverence and new storylines.

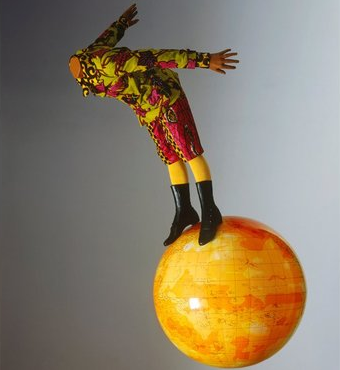

Pierre Huyghe gives us that most archetypal of figurative subject, the reclining female nude, but, unlike most reclining nudes, his Venus doesn’t have a head. She has a beehive. No, not a beehive like Amy Winehouse’s. A proper beehive. Full of bees. Watching them buzzing in and out of her head is disconcerting. Yinka Shonibare’s Africanised version of Degas’s Young Dancer doesn’t even have that. Just a stump on the end of her neck (as does his Boy on Globe). But she’s still standing. That’s modern medicine for you.

What’s actually being played with here is 30,000 years of trust and sanctity. From the moment the first genuine caveman roughed out the first fertility goddess from a lump of rock, sculpture has been depicting the human figure with profundity and seriousness. In today’s silly, celebrity-obsessed media world, however, that respect no longer seems honest or appropriate.

The brilliant Urs Fischer gives us a female nude so wonky that she has to rest her amputated leg on a breeze block to stand up. And look, there’s smoke pouring out of her head, because she’s actually a life-sized candle. Nearby, another telling Fischer sculpture shows a crumbling skeleton on a grubby park bench adopting what I believe is called the bareback position. Vesuvius has erupted again. And the inhabitants of the modern Pompeii have been frozen in all their contemporary squalor.

In the most visceral moment of a notably visceral event, Paul McCarthy confronts us with three versions of the same scarily lifelike nude, sitting with her legs wide open. In one version, she looks down at herself. In another, she shuts her eyes. In a third, she stares at us. The three sculptures work together like a flick book to give us an unfolding 3D moment of realisation and shame.

It is this visceral and inescapable involvement that makes the show potentially important. After all those years of slo-mo conceptualisation, how refreshing it is to be addressed so directly in a language the body understands immediately, and has always understood. Schütte describes the process of making the clay originals for his wobbly warriors as “thinking with one’s thumbs”. It is something art should do more of. Fingers crossed.

The Human Factor, Hayward Gallery, London SE1, until Sept 7