Here’s some tempting news. Or maybe not. If you visit Mondrian and His Studios, at Tate Liverpool, you will encounter “the largest number of neo-plastic paintings by Mondrian ever assembled in the UK”. The large number of Mondrians is certainly tempting. But neo-plastic paintings? What are those when they are at home?

Even by the hopeless standards of contemporary curator-speak, the term “neo-plasticism” is particularly unhelpful. Like so much of the language of modern art, it has a pseudo-scientific air to it. But it doesn’t actually mean anything. And no amount of repeating it — which happens a lot at Mondrian and His Studios — will ever help us gain a better understanding of what Mondrian was actually trying to do in his spare and deceptive abstract art.

I should quickly add that this is a beautiful show, and that the curatorial babbling in the texts and captions does not stop it from being a fascinating event. Any collection of Mondrian’s art is a cause for celebration, let alone the largest ever in Britain. His signature assemblages of primary-coloured rectangles enclosed in clean black grids are among the most distinctive achievements of 20th-century art. Besides, “neo-plasticism” turns out to be a mistranslation.

The phrase that Mondrian originally used in his native Dutch to describe his pictures was “nieuwe beelding”, which, when broken down, actually means something like “a new representation”, or “a new image”. Neither of those renditions sounds as art-historically mighty as “neo-plasticism”, but at least they point us towards something tangible. Mondrian was trying to represent the world around him in a new way.

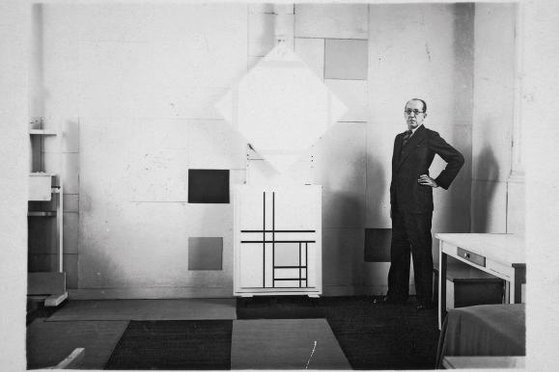

Inventively, but fuzzily, the Liverpool show tries to understand this progress by examining the studios he created during the final peripatetic years of his life, when the political upheavals in Europe sent him first to Paris, then to London, and finally to New York. Mondrian was a habitual rebuilder of his workplace. Wherever he moved, he would paint everything white, arrange carefully coloured rectangles on the walls, position the furniture just so, until the space he had made looked like a Mondrian painting. Or, seen another way, until the paintings he produced there came to resemble the space.

A marvellous re-creation of the best-known of these studios, the one in which he lived and worked in Paris from 1921 to 1936, at 26 Rue du Départ, gives this journey a spectacular beginning. Walking into the minutely reproduced space really is like walking into one of his pictures. Everything has been positioned with utter precision. The red, blue and yellow panels on the walls. The neat rectangle of the bed. The specific verticals of the easel. Even the coal for the studio stove was kept in a place where its blackness offered the sharpest contrast with the white wall behind.

Having re-created the studio, the show goes on to delight us with the paintings made in it. Here, Mondrian completed his transformation from a free-flowing, poetic abstractionist, who envisaged the sea at Domburg as a floaty fuzz of interlocking verticals and horizontals, into the ruler-wielding precision mechanic who encased bright rectangles of colour in strict grids of straight black lines.

By a happy accident, the upper galleries at Tate Liverpool turn out to be the perfect location for all this. Not only is the quality of the light coming in from the Mersey through the big industrial windows up here an exact accompaniment to the moist and airy colour schemes of Mondrian’s early seascapes, the gridded windows seem to have something pertinent to say on the matter, too.

Back at the re-creation of Mondrian’s Parisian studio, I was struck not only by the pictorial look of the space, but by the impact and position of the studio window: its patterns, its lines, how it let in the light in glowing rectangles. Positioned opposite his bed, the big studio window would have been the first thing Mondrian saw when he woke up. In the hands of a French artist — Matisse springs instantly to mind — studio windows had long been a favourite subject with which to play charming French reality games. Is it a picture? Is it a mirror? Mondrian, however, seems to have noted something bigger and more serious about the way the neat rectangles of light form glowing grids of reality.

As the show progresses, we get different descriptions of different Mondrian studios. In London, in Belsize Park, he lived next door to Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, and although his efforts at Mondrianising his north London bedsit are poorly recorded, his letters to Babs and Ben have survived, and are a joy to read.

In New York, where he arrived in 1940 on a steam ship from Liverpool — his Cunard passenger list is included in the show — he transformed a Manhattan apartment into another typical Mondrian. This time we have a good record of it, because immediately after Mondrian’s death, a faithful acolyte, Harry Holtzman, made an atmospheric film of the space.

Three cities. Three countries. Three different studios. All made to look the same. The show describes this situation atmospherically enough. What it doesn’t do is explain it. Having pointed out that Mondrian’s studios looked like his paintings, it fails to draw any meaningful conclusions from the observation. Fortunately, I think I can help there. It will, however, involve an examination of that creepy, pseudo-occult religion, theosophy.

One day, someone will write a big book on the remarkable influence of theosophy on modern art. Gauguin, Kandinsky, Klee, Malevich, Pollock and lots of others, but especially Mondrian, fell fully under its nonsensical spell. From 1909 until his death, Mondrian was a card-carrying member of the cult. A portrait of its fraudulent founder, the ridiculous Russian impostor Madame Blavatsky, was one of his most treasured possessions.

Having had several goes at reading Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine, theosophy’s most celebrated text, all I can really tell you with certainty about its mystifying message is that beneath the seeming chaos of the visible world, it proposes there is a secret unifying force at work. Hidden under what you see, says Blavatsky, is an underlying universal order. This universal order is explained diagrammatically on page 30 of Book II of The Secret Doctrine as a balance between horizontal lines, representing the female force, and vertical lines, representing the male force, enclosed in a circle.

Look at one of Mondrian’s early abstracted views of the sea at Domburg — a favourite theosophical haunt — and you will recognise a painterly version of a Blavatsky diagram. Yes, the strict verticals and horizontals have been tousled into beautiful pluses and minuses, and yes, the enclosing circle has been stretched into a relaxed oval, but the basic symbolic geometry is unmissable.

Like most shows about Mondrian, Mondrian and His Studios does not, of course, go into the wacky theosophical beliefs that underpinned his abstraction. To paraphrase Alastair Campbell on Tony Blair, the Tate doesn’t do God. Unfortunately, with pioneering modernism, you often need to.

Mondrian and His Studios, Tate Liverpool, until Oct 5