When I finally lifted my head from Building the Picture, at the National Gallery, I realised, with a grumble and a grunt, that I had been enjoying the show for five hours. How come? It’s tiny: a neat gathering of a couple of dozen Italian Renaissance pictures examining the role of architecture in Renaissance art. How can anyone spend five hours enjoying that? Reader, it happened like this.

First, I went to see the actual exhibition. That took 40 minutes. Next, I watched the five short films that accompany it. That took 20 minutes. Then I visited the bookshop and asked about the catalogue. That’s when a different set of chronometric laws kicked in. There isn’t one, I was told. However, you can find it online. So I went home, got online and began reading about Building the Picture on the National Gallery’s website. Four hours later, I was still there.

With its fertile combination of essays, diagrams, photographs, footnotes, cross-references, biographies, links to other texts that link you further, and so on, the Building the Picture web experience ought to carry a warning on its opening page: “Beware. You could spend the rest of your life on here.” Following my exposure to its bottomless joys, I now know the difference between Polish cochineal (Porphyrophora polonica) and Mexican cochineal (Dactylopius coccus), and how this important colorific difference may confirm the date of the velvet backing attached to Ercole de’ Roberti’s lovely Nativity of about 1490, one of the most pleasing images in a very pleasing show.

Polish cochineal, you see, has kermesic acid as its chief colouring constituent, while Mexican cochineal does not. So the purple velvet attached to the rear of de’ Roberti’s painting — which would previously have connected it to the Dead Christ that formed the other half of a foldaway diptych — was likely added before the import of Mexican cochineal commenced following the European discovery of the Americas in 1492. Easus peasus.

Just like St George and St John the Baptist, the two saints who attend the Virgin Mary in Lorenzo Costa and Gianfrancesco Maineri’s Virgin and Child with Saints, of 1498-1500, I was in heaven, enjoying hour after hour of exquisite art-historical nose-following. Did you know St George was actually a Greek, probably born in Palestine, and that he is also the patron saint of Beirut, Georgia, Moscow, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Syria, the Boy Scouts of America and all sufferers from syphilis, as well as of the city of Ferrara, where Costa and Maineri worked? So all you skinheads out there with St George tattooed on your necks, thank you for making so explicit your comradeship with the people of Bulgaria, Palestine, Montenegro, Syria and Beirut, as well as the Boy Scouts of America and syphilis sufferers everywhere. Bravo skinheads!

The show itself consists largely of pictures from the gallery’s collection that have been made to feel fresh and unfamiliar by a smart theme that prompts a different understanding of them. The main point the display seeks to make is that all the architecture we see here needed to be invented, and that the role it played in the meaning of the picture was, therefore, as significant as the role played by the figures.

I hate to think how many times I have walked past de’ Roberti’s Nativity without actually considering the significance of the way the stable is depicted, or, indeed, realising what a lovely painting it is. In trying to imagine Jesus’s birthplace in Bethlehem, de’ Roberti has come up with a wacky combination of a Greek temple and a Byzantine basilica, constructed entirely from wicker in the manner of a humble north Italian barn. The result is an extraordinary architectural concoction that remains true to the humble spirit of Bethlehem, but also predicts the creation of a grand and unshakeable Christian church.

The show starts with some thrifty illusionism: a plain grey arch above which sits a Madonna flanked by saints, just as she used to sit high above the streets of Florence in the 15th century. The niche she sits in is to be understood as a bridge between our world and her world, between earth and heaven. The artist’s task, therefore, is to imagine an architecture that no one has actually seen: an architecture that unites the divine with the worldly. Think about that proposition for a moment and you will quickly recognise what a tough ask it is.

In the clutch of enthroned Madonnas that follow, Renaissance art is tasked, also, with envisaging how a heavenly throne might actually look. Costa and Maineri present something lofty and vaguely Roman, with full-colour biblical scenes attached to all its surfaces. Domenico Veneziano, on the other hand, has something plainer in mind, an austere marble stack with the minimalist presence of a Carl Andre sculpture.

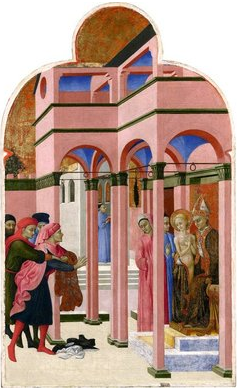

For every biblical story that needed to be illustrated, a new piece of architecture needed to be invented. To show St Francis denouncing his former life as a rich young man and entering his new life as an impoverished saint, the painter Sassetta reverses the obvious values and shows him encased in a bright pink arcade, while his angry father inhabits the empty space outside.

Lots of mental energy went into imagining Solomon’s Temple, destroyed by the Babylonians in 587BC, but the site of so many crucial biblical episodes. In his ruined but mighty Judgment of Solomon (1506-11), Sebastiano del Piombo presents a temple that is clearly based on a typical Roman basilica. Marcello Venusti, however, in his Purification of the Temple (after 1550), gives us something much stranger, created out of twisty columns and looming domes. In the accompanying film, a chap who designed the video game Ryse: Son of Rome makes the excellent point that designing the sets for modern video games involves exactly the same thinking as designing the architecture for Renaissance altarpieces.

All this is clever and stimulating. Ever since the studious Nicholas Penny took over as the National’s director, in 2008, the exhibition-making here has become thoughtful and instructive. And, although some might complain about the thrifty way the gallery reuses its own collection in these shows, rather than filling them with spectacular loans, I reckon this is the way forward: the new way of collecting, the eco way — not by spending zillions on new pictures, but by getting to know what you already own much better.