Whenever I see anything from Picasso’s Vollard Suite coming up for auction — which is often, because there is so much of it about — I skip those bits of the sale. If there’s one body of work in Picasso’s enormous output that seems unduly repetitive and maybe even boring, it is the Vollard Suite. Or so I have previously felt.

There are two problems. One is the size of this graphic monster. Consisting of 100 images produced between 1930 and 1937, each printed in an edition of 260, plus 50 more editions on larger paper, plus three sets on vellum, making 31,300 prints in all, the Vollard Suite is Picasso’s most long-winded achievement. In most of his art, he was the master of encapsulation, but the scope and circumstances of the Vollard Suite forced him into the production of a seemingly endless shaggy-dog story.

The second problem is the tone of the prints. How tremulous some of them seem. Particularly those featuring Picasso’s throbbing, hairy, overmuscled alter ego, the Minotaur, who spends the latter half of the Vollard Suite tupping defenceless blonde virgins with a brutality that makes you wince. If you don’t approve of bullfighting, you cannot approve of the Minotaur. From most modern angles, this testosterone-soaked monster-bonker is difficult to take seriously. Here, and only here in his enormous oeuvre, Picasso is guilty of melodrama and a disfiguring self-absorption. Or so I have always assumed.

Yet I have never seen all of the Vollard Suite displayed as an entity. Hardly anyone has — until now. The British Museum’s good fortune in acquiring a complete set of the prints, thanks to a donation by the art-loving city financier Hamish Parker, finally allows us to view and judge this notorious body of work with fresh eyes.

The 100 Vollard prints are clustered into thoughtful groups in the pleasantly subfusc prints and drawings galleries. At intervals, they are illuminated by appropriate classical statuary from the BM’s collections. Other prints by Picasso are included; and, where helpful, ones by Rembrandt, Goya and Ingres, the three old masters who influenced the Vollard Suite most mightily, are also shown. Thus, this enormous artistic banquet has been transformed into a set of manageable courses. I thought I knew the Vollard Suite well. I now see that I didn’t.

To begin with, it’s not really a suite. Yes, big chunks of the imagery belong together — the Minotaur pictures, for example, form a bullish cluster at the end — but what the BM manages to emphasise so successfully here is the variety of techniques and approaches that Picasso employs. Here, it’s his exquisitely precise line drawing that delights. There, it’s the foggy suggestiveness of his sugar aquatints. This is a violent sex scene. That is a lyrical dream picture. Here, he is brutal. There, he is gentle. Basically, we have 100 different prints here, pretending to form a set. Having previously believed that the Vollard Suite consisted of half a dozen great images and 94 interchangeable ones, I now know that every image has something further to offer.

The period in which the prints were made, 1930-37, was among the most fertile of Picasso’s career. In terms of creativity and obvious achievement, only his cubist years are a match. Predictably, because this is Picasso, it was a love affair that sparked him. In 1927, or some say 1926, he met a French schoolgirl called Marie-Thérèse Walter outside a Parisian department store. Depending on whether you believe the official or the unofficial version of this fateful meeting, she was either 17, the legal age of consent, or 16. My suspicion is that she was underage. What is certain is that she became the most exciting, the most sexually satisfying and probably the deepest love of his life. From start to finish, the Vollard Suite records her explosive impact on him.

Picasso was about to turn 50 when he began the sequence. His dealer, the notoriously vain Ambroise Vollard, who was worried that his star artist was about to defect to another dealer, pestered him into this unrealistic undertaking. Three of the prints that make up the 100, the three least inventive ones, are portraits of Vollard. He was also painted by Renoir (that portrait is now in the Courtauld Gallery) and Cézanne. Picasso produced a cubist likeness of his dealer, too, which is among his least inventive bits of cubism. Vollard could not inspire Picasso. But Marie-Thérèse Walter could, and did.

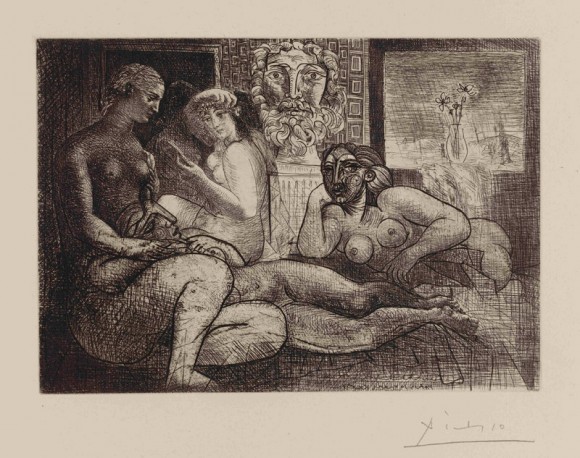

A sizeable chunk of the suite, 46 prints, is set in the artist’s studio. Inspired by Greek vases and Etruscan hand mirrors — thank you, BM — these delicate and spidery figure scenes usually show Picasso himself, disguised as a bearded sculptor, tackling the voluptuous likeness of Marie-Thérèse Walter. You can’t miss her. Her body consists entirely of the most delicious sculptural swellings. And in the unmistakable shorthand he developed for her, she always sports a prominent forehead and a nose that hangs down from this forehead like a dangling penis.

It’s rarely clear, however, if we are looking at Marie-Thérèse herself in these mysterious views of the studio, or a statue Picasso has just made of her. Her fate in the Vollard Suite is to blur the divide between life and art. As he shapes her likeness, the sculptor’s hands caress her curves like an eager lover fondling a body. Making art and making love have become interchangeable.

As he conducted this steamy love affair, Picasso was still married to his Russian wife, Olga. The curvy Marie-Thérèse was obviously a voluptuous alternative to the thin and angry Olga. Later in the sequence, when the Minotaur looms out of the dark to replace the classical sculptor as Picasso’s alter ego, the entire Vollard Suite changes pace and tone. The delicate mysteries of the studio morph into some of the most explicit and exciting sex scenes in art, as the Minotaur gorges himself on plump female flesh. Nowhere else in art — nowhere — has any woman been taken more tangibly than Marie-Thérèse Walter is taken here.

The other great passion expressed in the Vollard Suite is Picasso’s love of the Mediterranean. The constant references to Greek vases and classical statuary constitute a cri de coeur from a man of the south who has been exiled in the north. Olga, you feel, thin as a witch’s broomstick, has come to represent everything he loathes. Marie-Thérèse, plump as a Spanish tomato, is all he dreams of and wants.

As the 100 prints unfold in their increasingly urgent manner, their autobiographical presence grows ever fiercer. I found myself desperate for some trustworthy captions with which to understand this tumultuous and personal action. Where is Marie-Thérèse Walter leading the blind Minotaur by the hand at the end? Why does he appear so fretful? Picasso is too clever to tell us. His Minotaur’s fate is to wander tragically from conquest to conquest. Our fate is to wonder for ever about what is really going on in the marvellous Vollard Suite.