In art, as in most fields of endeavour, perception is all. And no important artist has survived as many changes in perception as Leonardo da Vinci. Before the National Gallery show devoted to his paintings, he was seen as an all-rounder of genius who did some art. After the National show, he was recognised as a painter of genius who did some all-rounding. Except, that is, by the da Vinci codists, who have never wavered from the conviction that he was the carrier of deep hermetic secrets about the origins of Jesus and the coming of the End of Days.

My own view of him has broadly been the middle one: that he was a great and important painter whose achievements as an inventor have been exaggerated. The scarcity of Leonardo paintings and their unavailability for travel has given too much prominence to his scientific drawings and impossible gadgets. There is hardly a sizeable town left in Italy today that does not possess some barmy Leonardo display filled with wonky flying machines and treacherous parachutes.

I therefore approached Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist as a nonbeliever who expected the National Gallery’s view to be confirmed. But it isn’t. Instead, this highly intelligent and excellently arranged display presents us with yet another Leonardo to cope with: Leonardo the resolute lab man, who came within a whisker of changing the history of anatomy. If he had published what we see him understanding here, he would have been up there with Galileo, Copernicus, Newton and Einstein. But he didn’t.

The Royal Collection is fortunate to possess the largest surviving collection of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings. They were saved by Pompeo Leoni, an early Leonardo fan, who, back in the 1580s, bought as many drawings as he could and preserved them in a beautiful leather-bound book, the cover of which opens this display. It was probably Charles II who acquired the drawings, whereupon they disappeared into the Royal Collection until their publication in 1900. So what we are looking at here is a set of sensationally prescient anatomical investigations, dating from the end of the 15th century, which remained completely unknown until the 20th.

Leonardo’s interest in anatomy started accidentally, as a by-product of his investigations into painting. He wanted to know how expressions appear on faces, so he began to take an interest in the make-up of the human head. Initially, he was content to accept other people’s researches on the subject. The first drawings here are devoted to some slightly potty pseudoscience. That strange section of a head with what looks like three sausages representing the brain — the opening exhibit in the National Gallery’s show — is here again. It illustrates the opinion that knowledge enters the brain via the first sausage, is organised in the second and is comprehended by the third.

This opening reliance on received wisdoms, or unwisdoms, leads quickly to a determination to investigate for himself. In 1489, Leonardo gets hold of a human skull and, in the show’s first batch of truly beautiful anatomical observations, cuts it in half and peers in. The secrets of the inner man quickly seduce him and, in 1490, he decides to write and illustrate his own treatise on anatomy. Everything else in the show can be understood as preparatory work for this treatise. Which he never finished. Had he done so, it would have counted as one of the most important scientific books ever published.

The show that traces these fascinating developments features the best use so far of the cramped spaces that make up the Queen’s Gallery. The Royal Collection is a hugely impressive hoard of art: to show it off properly, these rooms ought to be three times the size they are. In this instance, however, the smallness of Leonardo’s drawings suits the setting. Arranged into three helpful sections, the display also includes some lurid anatomical models that give it 3D heft. Thus, an event that could have felt bone-dry has a juicy and visceral presence.

Leonardo spends section two of the show dissecting real bodies and immediately acquiring a thoroughly impressive understanding of our inner bits. His first corpse is that of an old man who claimed to have been 100 when Leonardo watched him die. This famous corpse “del vecchio” results in a thorough investigation of human blood vessels and organs.

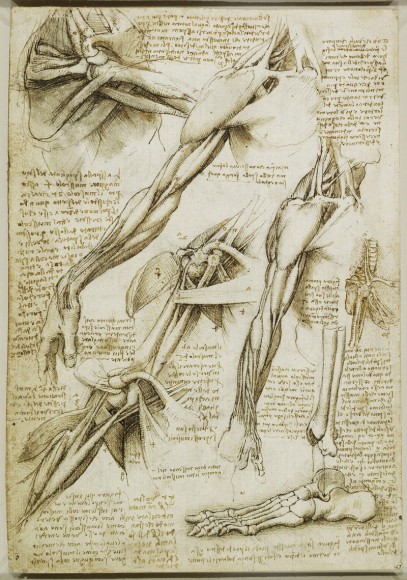

So accomplished is the presentation here of our inner biology, it’s easy to overlook the fact that Leonardo isn’t just progressing anatomical understanding. He is also inventing biological drawing. Today, we live in a world of plentiful biological illustration, and all these methods of explaining the inner body are familiar to us: the section, the inner close-up, the view across the cut, the map of the arteries, the exploded joint. In Leonardo’s time, they all needed to be invented. Here he is, turning abstract knowledge into a tangible and understandable visual coding.

The final room is dizzyingly impressive. It records his most sustained effort to turn his anatomical knowledge into a published treatise. Somehow, he gets to know the professor of anatomy at the university in Pavia, and the two of them embark on a thorough investigation of the skeleton and its muscles. A few of the sheets of intense, insightful drawings that result — a set of views of the inner workings of the human hand; a series of cross sections of the human shoulder in motion; the first accurate drawing of the human spine — are downright miraculous.

These sensitively shadowed drawings of body parts achieve so much more than is demanded of them. There’s a sense of movement, a thoroughly convincing corporeality and, above all, that uniquely Leonardoesque sense that you are somehow able to look through the human skin to a precisely observed inner reality: not an abstracted diagram of the stuff of life, but the stuff itself.

The unobservable is being observed here. And this utterly convincing sense of reality is Leonardo the artist’s greatest gift to Leonardo the scientist.