Try to imagine the beginning of Saturday Night Fever, with me in the Travolta role. If you remember, Travolta begins his big night with a slow, reverse striptease in which every item of clothing is carefully positioned on his body and then lovingly smoothed down. With me it was more a question of finding something that fitted and squeezing myself past its zip line. There were other differences. Travolta was going out to dance; I was going out to confront a dream. He didn’t wear National Health specs; I did. Most important of all, he was preparing for a night at the disco, while I was preparing to see David Bowie, live, at Starkers in Boscombe.

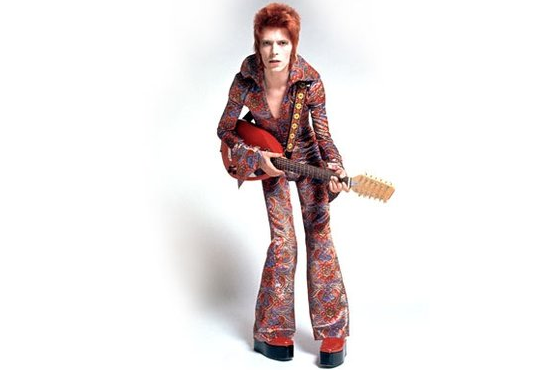

This being a Bowie article, you’ll be eager to know what I was wearing. Well, on my feet were a pair of platform-soled booties, brown and square-toed, zipped to the ankles. I remember them clearly because I only gave them to Oxfam a few years ago. For four decades they sat in my cupboard reminding me of the early 1970s. If you turn to page 25 of Speed of Life, the deluxe new collection of Bowie photographs we are here to admire, you will see Bowie wearing a similar pair, except his are red. That photograph was taken in the month I went to see him: August, 1972. His booties have 3in soles. Mine were substantially higher. He could stand up. I couldn’t.

Above his platforms, David sports a full-length zip-up catsuit with flared trousers and a floppy collar, coloured hippy-ishly in Indian paisleys. Funnily enough, I chose an Indian look myself that night, and went for a long-sleeved embroidered shirt from Afghanistan and an exceptionally skinny green boilersuit with sail-sized flarings.

Despite months of student starvation, I could only just get into the bottom half of that boilersuit. To this day I remember the harshness with which it lifted and separated my testicles. David’s Indian catsuit, I see, caused similar squashing in the basement. The things we Major Toms did to save the world in 1972: the ch-ch-ch-changes we went through.

Speed of Life is about the size and weight of a medieval bible. Tracking the transformations in Bowie from 1972 to 2009, it celebrates the work of the Japanese photographer Masayoshi Sukita, who first encountered Bowie-san about the same time I did.

Turning up in London in the summer of 1972, Sukita was a fashion photographer with a glam-rock fixation. “I had heard about T Rex and they appealed to me very much, even though I hadn’t heard any of their music. I had seen a photo of Marc Bolan in a Japanese magazine and noticed he was clearly wearing make-up, which I thought was pretty amazing.”

In London, Sukita found a Bowie poster in the street and begged his stylist to get him tickets for the Royal Festival Hall where the Ziggy Stardust/Aladdin Sane tour was about to chug off around the world; a few weeks later, this same tour would take Bowie to Starkers in Boscombe. Overwhelmed by what he saw at the Royal Festival Hall, Sukita went out the next morning and bought every Bowie record in the shop, and then wangled a meeting with Bowie’s manager. A few days later he was photographing the newest redhead in town. Forty years on, he’s still doing it.

Speed of Life is one of the new breed of limited-edition designer books which, like Bowie himself, straddle many genres. Part work of art, part bible, part memento mori, it comes with a beautiful insert of Bowie vinyl and a signed showpiece photo of Bowie in a hitherto- unseen role as a human clock. Edged with silver, patterned with silky blues and pinks, it’s an exquisite example of goody-bag publishing. You’ll need to rob a bank to secure it, but the photographs will make the stretch worthwhile.

In his introduction, Sukita remembers being struck by the sight of all the men in the audience at the Royal Festival Hall wearing make-up. “It really was a very exciting discovery for me, like an astronomer finding a new planet.” They were “like performers”, he sighs. Now that he mentions it, I do remember feeling pretty cocky as I hobbled down Christchurch Road in my 5in platforms into Boscombe Arcade where Starkers was located. In earlier times it had been a music hall. Max Bygraves had played there. I have no idea how it managed to ch-ch-change itself into a must-see music venue, but for a few months that summer, Starkers was the pl-pl-place to go.

In case you don’t know, Boscombe is a suburb of Bournemouth. Technically I suppose we should think of it as a seaside town, but that suggests an element of gusty marine sunniness that Boscombe never possessed. There was one cinema on Christchurch Road that showed soft porn for the old-timers in macs who made up much of the population. Their wives, meanwhile, would hobble to the cliff walk where you could spend the final moments before you died staring at the sea from a welcoming cluster of benches.

My mother moved there when I was 14 and opened the first Polish guesthouse in the Bournemouth area. It was called the Zywiec Guest House after the mountain town in Poland from which her family had spread. Zywiec was famous for its beer. It still is. A useful if accidental byproduct of calling the house “Zywiec” is that it made us the last number in the Bournemouth Telephone Directory. Anyone searching for a guesthouse could be directed to us with a minimum of fuss, and we also picked up a decent amount of passing trade. People used to phone up and splutter, “Is that the Zzrryzzccaaghgh Guest House?” before collapsing into giggles. Eventually, a sneaky coffee bar managed a to tunnel beneath us by calling itself Zzzebedees. The cheek of it.

The summer that Bowie came to play I was an art-history student at Manchester University, which, I’d like to think, gave me certain cultural advantages as far as Ziggy Mania was concerned. I knew exactly who David was singing about when he pointed out on Hunky Dory that Andy Warhol looked a scream and that he’d like to hang him on his wa-o-o-o-all. Me too.

It was Warhol, with his blond wig and his carefully achieved urban paleness, his deliberately wimpish handshake and his pioneering fondness for transvestite-chic, who invented the immensely attractive cultural idea that anyone could be whoever they wanted to be: identity could be shopped for and swapped about as effortlessly as a pair of shoes.

It became Bowie’s big idea as well. And the tour he set out on in 1972 featured his most determined efforts yet to become lots of people at once: Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, Major Tom, The Man Who Saved the World. That was just the beginning. The bewildering multi-identitied career photographed for us so sympathetically by Sukita-san in Speed of Life features enough different David Bowies to constitute a football crowd.

On his first Japanese tour in 1973, Bowie stripped off to a jockstrap and pretended he was a sumo wrestler — the world’s first 8st sumo wrestler! In 1980, while filming a soda-pop commercial in Kyoto, he became Chairman Mao —David Maowie! For the Serious Moonlight tour of 1983 he dyed his hair blond and began passing himself off as Heinz, the 1960s pop star from Eastleigh who, incidently, used to live next door to my auntie. On the cover of Heroes, Bowie became a leather boy. And in the Tin Machine days of 1989 he transformed himself — and this was rather unfortunate — into a dead ringer for David Brent. And I mean dead ringer. Becoming other people became the Thin White Duke’s way of being himself.

All this Sukita records in his big thick deluxe book with perfect Japanese empathy. In my experience, the Japanese have a different understanding of artifice to the rest of us. They celebrate it. Chase it. When David Jones from Brixton turned into Ziggy Stardust, he was effecting a transformation that any geisha of the post-Edo world might recognise. The Japanese welcome such transformations instinctively. In Masayoshi Sukita, Bowie has found a photographer who never needed to be told what he wanted. Sukita’s empathy was natural and reliable.

I, alas, was not in the same boat. To this day, to my great cultural shame, I have never dared to wear make-up. And the only time I have stepped out in drag was for a student rag stunt. These days, having seen Madonna swap identities as easily as a pair of gloves and watched Lady Gaga apeing Dali in her sartorial taste for lobsters, we are pretty used to the idea of the pop star as chameleon. Back in 1972, in Boscombe, it was new news, believe me.

Earlier that summer, Led Zeppelin had played Starkers and shook the old music hall so hard its fillings fell out. Then came the Kinks, whom I missed. Then Thin Lizzy, whom I don’t remember because they were blown off the waterfront and out to sea by Slade, whom I will never forget. Noddy Holder was on fire that night. You could hear him instructing Boscombe to feel the “noize” from the other side of the New Forest.

That summer, I was working on the beach, manning a kiosk that sold teas and ice creams to the grockles. As summer jobs go, this one was unsurpassable. Not only could you make piles of money fiddling the tea resources — the recommended dose was one teabag per cup, but with a bit of Polish brutality you could easily squeeze 10 cuppas from a bag, at 20p a cuppa — but during quieter spells you could sit on the edge of the ice-cream fridge and chat up the passing honeys. What is it about guys in uniforms? All I had on was a standard-issue white catering top, but as far as Mandy from Wakefield or Deborah from Wolverhampton were concerned, I could have been Bowie himself in his ship-captain-from-Monaco phase. Never before in my life, and never since, had I managed to talk to so many girls.

Not that any of them wanted to see him with me. I ended up going with a bunch of mates. The entrance fee to Starkers, if I remember correctly, was 90p on the door. By the time I got there, having tottered all the way up Christchurch Road in my platforms, my feet were oozing blister juice mixed with blood, and my poor boiler-suited testes felt as if someone had attempted to saw one away from the other.

Bowie came on with a saxophone which, alas, sounded rather weedy in the echoing music-hall vastness of Starkers. Costume-wise, he embarked upon a busy series of ch-ch-ch changes, none of which seemed entirely serious. I don’t know what I was expecting but it was something bigger, beefier, fuller than the nervous squeakiness I was witnessing on stage. He was horribly thin as well. And how he had convinced himself that he looked good in hot pants I don’t know, because he definitely did not. To make hot pants work you need a pair of legs and not two knitting needles. The combination of spindly legs and bright red hair brought out the Pinocchio in him and made him look puppety. I don’t think I have ever seen anyone on stage who seemed quite as cold or as uncomfortable as David Bowie playing Starkers in Boscombe on August 31, 1972. This really wasn’t his world.

To find out what was, glide slowly through the deluxe, elegant, expensive pages of Speed of Life. And watch Ziggy Stardust come to life in the exquisite, grainy, far-away photography of Masayoshi Sukita.