Poor Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec — thoroughly famous, yet thoroughly unknown. Few of us have any difficulty imagining him. But it is always the same reductive and misleading image. Small man. Big drinker. Small legs. Big head. Big penis. Bowler hat. That’s Toulouse-Lautrec.

Some of the blame for the cursoriness of this notorious image needs to be dumped on Lautrec’s own doorstep. Among his most dazzling talents was a cartoonist’s ability to sum people up with a few telling strokes. By the time he had finished portraying the great cabaret star Yvette Guilbert, all he needed to draw was a pair of thin black gloves waving in the air and everyone knew exactly who he meant. Unfortunately, what Lautrec achieved for others he also achieved for himself: the supplanting of the reality by the image.

The comic self-portraits he produced of a Chaplinesque chappie in a bowler hat have etched themselves too successfully into our global consciousness.

So we always get him wrong. And forget that he painted some of the warmest and most loving portrayals of women of his era; that his technical experiments were fearless and astonishing; that his draftsmanship was in the Degas class; that he was an unusually empathetic portraitist as well as a designer of genius; above all, we forget what a Nostra-bloody-damus he was.

Lautrec understood better than most what the world was becoming. In particular, he understood that if you put a sexy girl on the cover, it will sell.

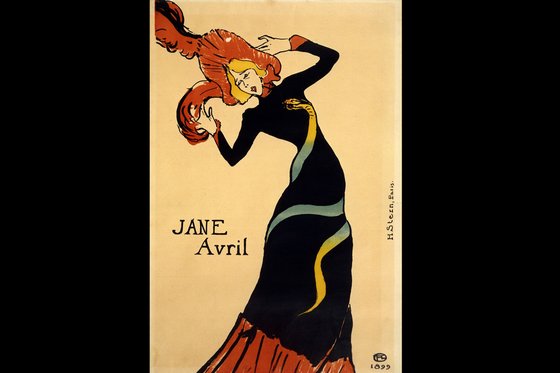

Which brings us to Jane Avril. Who is simultaneously typical of Lautrec, and very different. She is typical because she was a dancer at the Moulin Rouge. And the posters he made of her are among his most famous images: Jane Avril kicking up her leg in a frilly cancan; Jane Avril taking a slinky drink at the Divan Japonais. You know the posters. I know them. Everybody knows them.

But Avril is untypical, too, in being a damaged character who became the artist’s close friend. Having shaped her image, he also confronted her reality, and painted her with real psychological insight. That is what the Courtauld Gallery’s new show seeks to commemorate: a professional relationship that became a rare intimacy.

We should deal, straightaway, with the question that may now be in your thoughts: were they lovers? Probably. According to legend, Lautrec kept pestering her to go to bed with him and finally she acquiesced. “Just once. Out of friendship.” I would be surprised if there was never an occasion during the drunken, squalid, nocturnal existence they shared for a decade when desire took over.

Lautrec was as addicted to sex as he was to alcohol. But the Courtauld, being the scholarly institution it is, prefers not to speculate on such lowly matters and focuses instead on Avril’s intriguing character, her strange past and the weird dancing style that made her unique.

Before we buy too wholeheartedly into the mythic and ethereal Jane Avril explored for us here, however, I recommend a quick glance across at the most famous of the great posters he made of her: Jane Avril at the Jardin de Paris, printed in 1893. It’s the one in which she dances a cancan in the background while a huge, disembodied hand plays a double bass in the foreground. Sorry, but that is a momentous image of male masturbation. Look at those hairy knuckles clasped firmly around the neck of the bass. The double bass becomes a giant penis. Lautrec is presenting the open-legged Jane Avril as an object of tumescent masculine desire.

That admitted, the main point of this show is to celebrate an unusual relationship between an artist and his muse. Lautrec seemed never to tire of Avril. He kept picturing her, again and again. Not only does she appear in some of his most famous posters, he painted her frequently in her civvies, too: a hunched silhouette at the back of the bar; a lonely, late-night figure leaving the Moulin Rouge at the end of the night. It is this confluence of private and public imagery that makes their relationship special. She was the damaged goods. He was the concerned observer.

So who was Jane Avril? She was born Jeanne Beaudon in 1868, the daughter of a prostitute from Belleville, Paris. When the mother’s looks went, and her income fell, Jeanne was pushed out into the streets, where she was savagely abused and exploited. At 13, she was diagnosed with a curious neurological condition commonly called St Vitus’ dance. Modern doctors know it as Sydenham’s chorea.

This weird illness, examined in depth in the documentary sections of this show, causes the limbs of its sufferers to jerk uncontrollably. According to Avril’s own version of events, she was sent to a Parisian institution that specialised in neurological diseases, the Salpêtrière hospital, and it was during one of the balls organised by the hospital that she discovered her love of dance. It was like falling into a trance: dancing soothed her spirit and brought her peace. Later, a poetic English boyfriend advised her to change her name, and before you can say Sydenham’s chorea, Jane Avril was a dancer at the Moulin Rouge.

It’s a resonant story. But was it true?

The Courtauld thinks so and has devoted much effort to rounding it out. I have some suspicions. There seems something overly convenient about the connection of Avril’s dancing style to the story of St Vitus, patron saint of dancers, whose followers were famous for cavorting hysterically before his image. Was the St Vitus’ dance story a successful bit of Moulin Rouge PR?

One thing is certain: Avril in action was an extraordinary sight. “An orchid in a frenzy” was how one writer described her. Tall, thin, willowy, double-jointed, her dance was bewitchingly strange, and where most of the cancan girls at the Moulin Rouge performed in troupes, Avril preferred to go solo, bending and twitching inventively. The painter William Rothenstein remembered her as “a wild Botticelli-like creature, perverse but intelligent”. While the English poet Arthur Symons, transfixed by “a white bodice opening far down a boyish bosom”, detected in her an air of “depraved virginity” and “the beauty of a fallen angel”.

Steady on, boys. Whatever it was that Avril had, it did powerful things to watching chappies. Just as clearly, though, she had a rare complexity to her. Compared with the other dancers of the Moulin Rouge, notably the hefty and burlesque La Goulue, notorious for dancing the cancan sans culotte, whom Lautrec also portrays in this show swaggering around the Moulin Rouge, Avril was a peacock feather next to a pork chop. Or perhaps a volume of Proust next to a Mills & Boon paperback.

Just about all of Lautrec’s most important images of her are here. Great care has been taken as well to secure crisp, fresh imprints of those horribly famous posters. Lautrec had a thing about redheads, and even though Avril seems not to have been a proper one — judging by the afore-mentioned visitor memoirs, as well as the photographs gathered here — in his sexy, slinky portrayal of her in a black dress at the Divan Japonais, he gives her the coloration of a glowing match. However, in the poster of her doing the cancan at the Jardin de Paris, she’s become an amber blonde.

This sense of an identity in flux is exaggerated by Lautrec’s flickery, restless touch in the paintings of her dancing.

An early sketch, painted quickly in vibrant blues, shows Avril’s angular figure lurching forward in a kind of hysterical goose step. Even when she performs the familiar cancan, there is something verging on deformity about the spiky postures she adopts: the thin legs, the protruding bones. Most of his paintings, however, show her after hours. The Courtauld’s own Lautrec masterpiece shows her leaving the Moulin Rouge at the end of the night, a pinched and haunted figure, bundled up in a big coat, from which a thin, pointy head emerges at a hunched angle more often seen on vultures.

One of the reasons the exhibition is so exciting is because the loans to it are so impressive. The Art Institute of Chicago has lent one of Lautrec’s most celebrated pictures to the show, the famous interior At the Moulin Rouge, in which Lautrec himself can be seen at the back making a late-night exit with his extra-tall cousin, while Avril sits in the foreground with her back to us, instantly recognisable because of the flaming red hair. Either that or someone has opened the door to a furnace in the middle of the picture.

All this is impeccably presented in a show that does several things very well: it reminds us what a brave and inventive artist Lautrec was; it brings to life a formerly shadowy heroine of the Moulin Rouge; and it celebrates a unique working relationship between an unusual creative and his even stranger muse.