Every generation reinvents the artists of the past in its own image. And the case of René Magritte is an excellent example of this truism in action. In my lifetime, I have had three distinctly different Magrittes presented to me. All felt right at the time, including the latest one, the Duchamp-flavoured Magritte now explored in careful detail by the Tate in Liverpool.

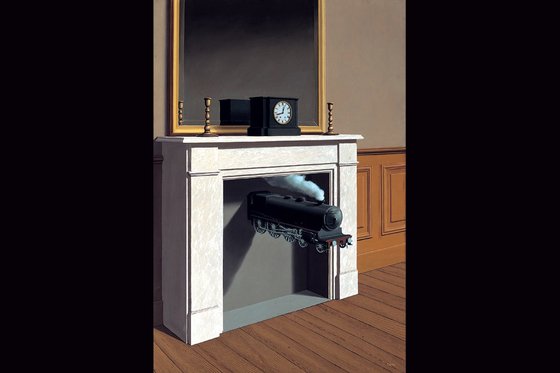

When I was a student, the Magritte served up in my lectures by the serious modernists who shaped me was a shallow painter whose visual trickery was considered amusing but trivial. At the time, too many Magritte trains were whistling out from too many mantelpieces on too many Athena posters for his achievements to appear weighty. After I became an art critic, the Magritte mood gradually darkened, and by the time the Hayward mounted its ambitious retrospective in 1992, he was widely recognised as a sexual obsessive with a strange mind: a proper surrealist.

I remember being sent to Belgium to write what they optimistically call a colour piece about his origins and finding myself in the ugliest corner of Europe I had ever visited. Châtelet, where he grew up, smelt of chip fat and suicide. The river into which his mother threw herself when he was 14 was the colour of diesel oil. When they pulled her out of the water, with her son watching, her nightdress was wrapped around her head. The rest of her was naked. A few years after my visit, in Charleroi, the next town along, where Magritte went to school, that beast of a man Marc Dutroux raped and murdered little girls, whom he kept locked in his basement. I recall thinking how unsurprising that was.

That was then. Now, at Tate Liverpool, we get something brighter, less loaded, less emotional. By doing away with his life story altogether, and taking us instead on a thematic bumper-car ride through all corners of his output, the show gives us a new Magritte: the deconstructivist, skilled conceptual tinkerer with image and time, prophetic explorer of the virtual, who understood before most that reality isn’t real, it just looks as if it is.

This new Magritte makes his debut here in a room filled with repetitions. These images of doubling up come from all parts of his career. All seem to be noticing that if you picture a thing twice, you diminish its sense of self. (Sorry, but this is a slippery show whose review is going to involve the use of slippery language: bear with me.) On its own, Magritte’s portrait of his fellow Belgian surrealist Paul Nougé in a smart tuxedo would have seemed a straight-forward piece of robotic portraiture. Put two identical Paul Nougés together, side by side, though, and you achieve instant weirdness: man reduced to wallpaper.

In the same room, we find Magritte’s spooky presentation of a pair of kissing lovers with both their heads bandaged in white cloth. In the Hayward’s Magritte retrospective, this disturbing painting, The Lovers, made in 1928, was presented as a key surrealist image whose claustrophobic and fetishistic effect needed to be understood as a response to his mother’s horrible suicide. When I stared into the black waters of the River Sambre in Châtelet, where she was dragged out, I certainly felt no other understanding was possible. Here, though, the two kissing heads are presented as further examples of his love of repetition. New understanding has become no understanding.

The opening emphasis on Magritte the image pirate continues for the entire first half of the show.

Dispensing with chronology, the display homes in instead on the artist’s fondness for patterns, illusions, trompe l’oeil and word games. The obviously surreal Magritte, combiner of women and fish, painter of raining men in bowler hats, is held back for later. Instead, we are confronted by an inveterate swapper-around of looks. Smoke becomes stone in one painting. In another, glass becomes paper. In a third, solids become liquids. These are some of Magritte’s least sexy images. Previous generations have understood them as his dullest paintings. Here, they are presented as his cleverest.

The rethink reaches a climax in a gloriously puzzling room filled with his word pieces. It is here that pipes turn out not to be pipes, shoes become moons, rocks become clouds. By lumping together all the word pieces like this, the show makes clearer than it has been that it is the strangeness of the words themselves that Magritte is exploring. All of us have surely experienced a moment when a word we use often suddenly appears weird.

I remember a long afternoon spent puzzling over “through”. Someone please explain “through” to me. Magritte was also interested in the fragile relationship words have with the things they describe. If you look hard enough at the word “pipe” and, alongside it, at the image of a pipe, then both of them, word and image, begin to take on an unaccountable strangeness. That is the sensation he sets out to capture. In these wicked hands, the statement below a pipe that the pipe above is not a pipe begins to make worrying sense.

Also here is a carefully painted piece of cheese displayed under a glass bell, with the words “This is a piece of cheese”, when clearly it is not. It is a painting of a piece of cheese. Just as the pipe is a painting of a pipe, not an actual pipe. Thus the show, successfully and fascinatingly, relocates Magritte in the Duchamp camp, where various aspects of his art begin to make a different kind of sense. For once, the thematic approach modern exhibitions are so fond of adopting at the expense of a legible chronology bears valuable fruit.

Magritte himself referred to the sensations of strangeness he was searching for in his paintings as “the poetry of things”. He understood this poetry as something valuable and life-enhancing, an antidote to banality. The idea of his art was not to puzzle us. The idea was to make us look at familiar things with unfamiliar eyes.

The show also makes clear that commercial considerations had an impact on his thinking. For much of his career, Magritte, like Andy Warhol, whom he also resembles more here than usual, kept a toe in the commercial world by working as a designer of posters, wallpaper, pamphlets and theatre sets. A fascinating selection of this commercial work is here. There’s Magritte advertising Belgian toffee. Magritte imagining film stars. Magritte selling cigarettes. It’s immediately obvious what a good designer he was, and why his work has had such a powerful influence on modern advertising. Surrealism can be missed. Catchy posters can be missed. But catchy surrealism will always have an impact.

Up to this point, the exhibition succeeds impressively in understanding Magritte in new ways. Yet most visitors will be noticing by now that they are halfway through the show, but that, apart from the pipe that is not a pipe, they have barely encountered a familiar Magritte image. No bowler hats or apples, no trains or mantelpieces, no two-part nudes or petrified interiors. Worry not. A superb selection of all the above awaits you. Having made its point about new ways of understanding Magritte, the show changes tack and goes back to the old way. The room devoted thematically to The Fractured Nude is full of slippery, sexually charged portrayals of his foxy wife, Georgette. First he stacks her in bits like a Russian doll. Then he replaces her nude shadow with a nude drawing of her. What he can never get rid of in his portrayals of Georgette is a tangible sense of his desire. Yes, there is something Duchampy and conceptual about much of his output. But not when Georgette poses for him.

In a mildly creepy inner sanctum, the Tate has hidden away the pornographic drawings Magritte made to illustrate a book by Bataille. They attempt a rare combination of pornography and slapstick. A woman attempts to fellate a disembodied penis by sucking the wrong end. As I write, the adjacent image of a madly masturbating Jesus is still in the show. By the time you read this, the forces of propriety may have succeeded in getting it out.

Another section deals with the pictures of pictures within pictures. Then come the bowler-hatted chappies falling out of the sky like the rain at Glastonbury. Finally, a particularly enchanting thematic grouping brings together a dozen of those haunting urban views in which night becomes day as soon as it climbs above the tree line. So it’s a schizophrenic show as well as a fascinating one. The first half feels hardcore and demanding as it reimagines a new Magritte for the computer age. The second half stops thinking and starts enjoying.