As it’s Valentine’s Day, many of us, the fortunate ones, will have stridden into the morrow with our lips parted expectantly. Even if it’s just a loyal peck on the cheek, rather than the full Picasso, we expect today to involve some form of osculation. The question is: why?

No one knows for certain why we kiss. Behavioural scientists and anthropologists have unshelved a batch of theories, without settling on any of them. Kissing is instinctual, say the lab boys. It’s related to premastication and breast-sucking.

Having watched a lot of David Attenborough, the explanation that sounds most right to me is that it’s a way of checking the health of a potential mate by inspecting their saliva. That definitely triggers memories. It also explains why Leonardo DiCaprio, having planted one of the silver screen’s most memorable smackers on the lips of Kate Winslet on the deck of the Titanic, could also remember his first Frenchie in such harsh detail. “The first kiss I had was the most disgusting thing in my life. The girl injected about a pound of saliva into my mouth, and when I walked away I had to spit it all out.” She was testing you, Leo, and you failed!

The uncertainty of anthropologists is another reason to be grateful for the clarity of art. Sucking face may remain a mystery for behavioural scientists, but for artists it is enough that we like doing it, and that they like watching us do it. That’s why our museums are alive with the sound of snogging.

Evidence of human mouth exploration goes all the way back to the Sumerians. “When my sweet precious, my heart, had lain down too, each of them in turn kissing with the tongue,” goes a famous Sumerian poem, remembering a pleasing throatie.

Away from the sexual acrobatics recorded on the sides of vases by those determined sensualists the Greeks, the earliest kiss I have been able to identify is Giotto’s 14th-century depiction in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, where St Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary, is shown delicately muzzling her husband, Joachim, at the Golden Gate in Jerusalem.

Joachim has been banished from the city because he has been unable to father a child. So the temple worthies send him into the desert for 40 days. When he returns Anne tells him she is finally pregnant, and they embrace warmly. It’s a genuinely touching hug, although the mysterious figure in black lurking behind them appears also to prefigure dark times ahead.

What’s especially telling about Giotto’s kiss is that in 1305, when the Scrovegni Chapel was painted, the painter was already aware of a difficulty that Ernest Hemingway would later dwell on in For Whom the Bell Tolls. “Where do the noses go? I always wondered where the noses would go.” Giotto’s answer is to have Anne grasp Joachim by the back of the neck and come in from the side.

Later in the Renaissance, when affection grew freer and more inventive, the antics of Jupiter, the randy king of the gods with a taste for beautiful mortals, gave artists more room to experiment. Correggio, the most imaginative of the Renaissance’s many recorders of Jupiter’s Weinsteinian appetites, came up with the creepiest Renaissance kiss of all when he painted Jupiter, disguised as a cloud, seducing Io. Her back stiffens, her lips part. She’s being embraced, but by what?

There is plenty of osculation in the rococo era, but it tends towards the routine. At first sight, Boucher’s famous depiction of a face-lock in his Hercules and Omphale features a standard meeting of mythological lips. Only when you peer more closely does it become apparent how much personal experience has gone into the description.

To solve the nose problem, Omphale and Hercules have both turned their heads anti-clockwise. But look at the momentous suction she’s exerting on his quivering mandibles. A famous line of Christopher Marlowe on the subject of Helen of Troy springs instantly to mind: “Her lips suck forth my soul, see where it flies.”

For most of the 19th century nothing exciting happens in the depiction of the kiss. But it’s just the gods of art stretching out the foreplay. The most famous of all kisses in art, Rodin’s momentous hug in the buff, was finally carved in 1882 and, as with the Boucher that inspired it, the naked woman in the huddle is once again doing most of the munching. Edvard Munch himself, meanwhile, in The Kissfrom 1897, avoids all such specificity and reduces the embracing twosome to a single blob. It’s unclear where she ends and he begins.

My personal favourite in this glut of fin-de-siècle snoggery is Toulouse-Lautrec’s beautiful and touching depiction of the girl-on-girl kiss recorded in a Parisian brothel in 1892. For Lautrec, the brothel was a home from home. Outside, he felt a freak; inside, he didn’t. The girls liked him and shared their vulnerability with him. And to his observations of them he brought an empathy and an honesty that were precious and rare.

Lautrec is always underestimated. Gustav Klimt, d’autre part, is habitually overestimated. Klimt’s Kiss, from 1907-08, is probably the best-known depiction on the landing side of the fin de siècle. It’s pretty and golden, but only tangentially about kissing. Mostly, it’s about completing the decor.

The other widely celebrated kiss from the beginning of the 20th century, Constantin Brancusi’s, in which two stone slabs are locked in an implacable embrace, has always struck me as unintentionally comic: Fred and Wilma Flintstone on a first date.

It is left to Picasso to rescue the face-suck from this dry-stone-walling with a sequence of outrageously moist kisses that begin in his Blue Period and continue to the end of his career. Seventy years of swapping saliva, and all of it memorable.

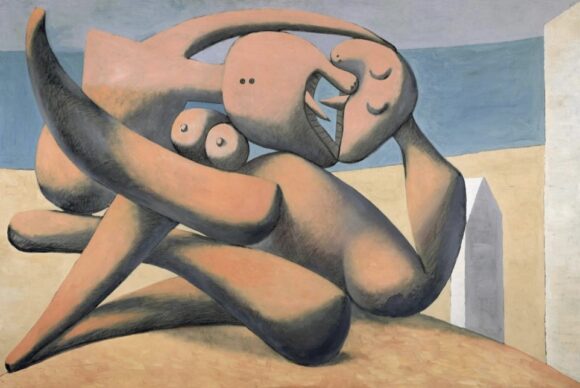

Like the ancient Sumerians, Picasso is a tongue man. In most of his depictions of the Spanish knot, the tongues meet at the epicentre of the action like a pair of clashing blades. The sexual rawness of his depiction was brought home to me when I was browsing the label for his shockingly direct Figures on a Beach in the Musée Picasso in Paris, and happened to read that it was painted on January 12: my birthday!

Two interlocking blobs, naked as the day they were born, are going at it like the clappers. So intricately are they entwined that it’s unclear which bulge belongs to whom. To solve the nose issue, Picasso has chosen the path open to cubists of moving hers up, and his down. Et voilà! As for the tongues — I’ve seen gold medals won at the Olympics for displays of fencing less fierce than this.

I don’t know about you, but I’d rather not be encouraged to visualise so clearly what my parents got up to to create me. Yet here was Picasso forcing me, it seemed, not only to imagine the act itself, but to shudder at the inventive stuff that preceded it. Frankly, I’m with Giotto on this one: it’s the angels what done it. Happy Valentine’s Day.

The National’s top paintings

Most of the galleries closed down by Covid-19 have sharpened their internet presence. The National Gallery in London has been particularly busy with virtual tours, short films, video lectures. And it has just announced a Top 20 of its most popular paintings, based on internet clicks.

At No 20 is the portrait of Sultan Mehmet II by Gentile Bellini. Hah! Plenty of people reading this who know the gallery well will be unaware there was a portrait there of Mehmet II by Gentile Bellini.

Historically, it’s an interesting enough thing, offering proof of the close links that existed in the Renaissance between Venice and the East. But as a portrait it’s pint-sized and plain. How did Mehmet II get on to this list while Van Dyck’s magnificent equestrian portrait of Charles I did not?

At No 1 there’s another surprise. The most clicked-on picture is The Arnolfini Marriage by Jan van Eyck. It’s a fascinating painting, but in terms of scale, breadth, artistic presence, it’s relatively modest and no match, surely, for the big Leonardo or the astonishing Titians?

What we’re witnessing here is, clearly, the impact of the internet. With the Mehmet II and the Van Eyck, different attractions come into play. The first is reproducibility. Things work differently on a computer screen than they do in the flesh. Smallness isn’t just an irrelevance, it’s an advantage. And the glaring domesticity of the Van Eyck — bloke, woman, dog, in a room — appears to be ringing a Covid bell tone.

Perhaps Mehmet II is the subject of a home school project? Or maybe the sight of his handsome turban is all we need to trigger dreams of getting on a plane and flying somewhere, anywhere, as long as it’s far away.