My kerrrannnng! moment at the Manga show in the British Museum was when I realised how much manga has in common with Michelangelo. It isn’t just a taste for compartmentalisation that they share — the way the individual scenes on the Sistine ceiling can be read as a continuing biblical story that develops from the back of the church to the front. Deeper than that is the visceral nature of the communication.

Michelangelo painted all those connected scenes of creation and collapse on the Sistine ceiling because pictures don’t need to be learnt in the way that language needs to be learnt. They speak to the viewer instinctively and subcutaneously. The Renaissance began painting all those story cycles in all those frescoes because it wanted to turn two-dimensional sights into a three-dimensional experience: to combine width with depth. Kerrrannnng!

For those of you who live on the planet Zog and do not know what manga is, or why the British Museum might now be examining it in an ambitious genre survey, allow me to taunt you with a quote from the advertising blurb in the catalogue, which insists that manga “is fast becoming a universal visual grammar for our globalised age”. That’s right, Zoglander. This is something you need to learn about fast, because if you don’t you’ll end up wandering forlornly about the kingdom like a lonely ghost in Spirited Away.

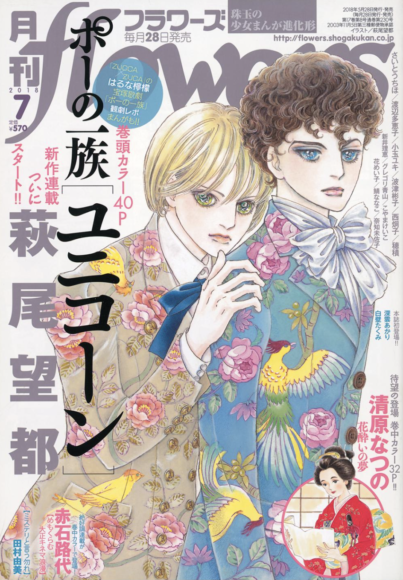

In prosaic terms, manga is the word for Japanese comics, or, to use our own charmless term for the form, graphic novels. The word is derived from two roots, “man”, meaning rambling, and “ga”, meaning picture. If you’ve been to Japan, you will know already how popular these rambling pictures are in Japanese society. In bookshops, manga volumes in their millions overflow from the shelves like the waters of Niagara Falls. On trains, 90-year-old bonsai masters can be seen flicking eagerly through the latest Dragon Ball adventure. Kids read them. Grannies read them. Salarymen read them. Air hostesses read them. Classless, ageless, infinitely varied, manga is a cultural glue that holds Japan together.

However, the British Museum would not be devoting this much space or energy to it if it were only a Japanese printing phenomenon. In recent years, this cultural tsunami has burst its national banks and poured into the rest of the world. Not just into other people’s comics history, but into the territories of cinema, advertising, toys, television, video games, rap music, even car design. The British Museum is seeking energetically to understand manga not because it’s a Japanese cultural phenomenon, but precisely because it isn’t. Not any longer.

You may already have guessed from my excited tone that they do it really well. On paper, the BM’s journey through the 1,000-year history of manga is divided into six self-contained chapters that build into the complete story. There’s a chapter about how manga are made. Another about manga and society. A third about manga’s expansion into other art forms. But dividing manga into chapters is like trying to herd a swarm of bees into rectangles. It just won’t happen. There’s too much energy, too much disobedience, too much buzzing from flower to flower.

For me, the show felt more like stepping in front of a water cannon that blasts you, from start to finish, with a torrent of sights, insights, histories, examples, interviews, drawings, connections, layouts and spectacular mood changes. My advice is to step happily into the cascade and just follow where it pushes you. The overall picture will be blurred, but individual moments will stay pin-sharp in the memory.

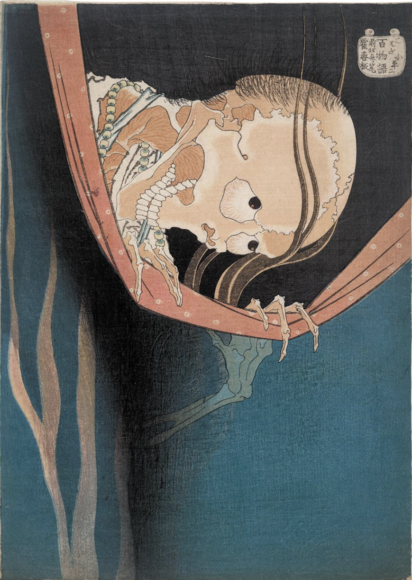

According to Osamu Tezuka, the inventor of Astro Boy and the widely worshipped “god of manga”, it all began 800 years ago with an unfolding scroll called the Choju-giga, a beautifully drawn tale of frolicking animals that belongs to the Kozan-ji Temple, in Kyoto. Probably drawn by an artist-monk called Toba Sojo around the time when shaggy French masons were darkly digging the gothic foundations for Notre Dame, the Choju-giga is a sophisticated bit of anthropomorphic satire in which a cheeky gang of rabbits, monkeys and frogs take the mickey out of the monks they pass in their frolic.

Pretty much every cartoon feature of the future — talking animals, distorted scales, mad chases, things going wrong, frogs as big as rabbits, rabbits as big as monks — is invented in this shockingly timeless classic. To think that Toba Sojo was having all this crazy pictorial fun while we were doggedly completing the Magna Carta. It’s a cultural comparison of startling vividness.

Tezuka tells us about the Choju-giga in one of the many helpful video interviews that stud this frantic journey. I don’t know if the organisers here were deliberately using the frolic of the animals as their exhibition model, but the mood they have achieved is eminently comparable. What we have here is a sustained display of organised chaos.

In any manga show, the obstacles that need to be overcome are many and varied. First, there is the language. It isn’t just Japanese itself that is fiendishly difficult for us gaijin to penetrate. The onomatopoeic comic language of DODODODOS, BOKOBOKOS and ZAKUZAKUS is hardly a cultural doddle, either.

Then there is the fact that manga, like Japanese writing, needs to be read from right to left, and in an anticlockwise direction. This is a mind-scrambling difference that tests your concentration with every sequence. The show tries kindly from the off to prepare us for all this reversality with charts and diagrams, but the sense that you are starting with the Game of Thrones finale, then working forwards to the beginning, is a powerful confusion that never lets up.

In an effort to make the journey easier for western imaginations, the BM ropes in Alice and her rabbit to pop up at the top of the show and open the doors to Wonderland by beckoning us into their hole. But for me this is one of the few mistakes the exhibition makes. It is the ways in which manga differs from the Alice in Wonderland model, rather than the similarities, that make it so fascinating.

Modern manga, postwar manga rather than the original 12th-century variety, was born in confusing cultural circumstances. Having lost the Second World War, and having had a nuclear bomb dropped on it, Japan was forced into an unequal relationship with American culture that proved, amazingly, to be very fruitful. Tezuka admits happily to being prompted to start his manga adventures in the 1940s by Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse.

But the kinds of adventures manga was soon getting up to were nothing like the kinds of adventures favoured by Donald and Mickey. In My Brother’s Husband, by Gengoroh Tagame, a pair of middle-aged male lovers spend their manga moments swapping delicious dinner recipes with their readers. In Hinako Sugiura’s Miss Hokusai, the 18th-century world of the great Japanese printmaker is observed through the eyes of his talented daughter Oei. In Blue Giant, by Shin’ichi Ishizuka, the hero spends the entire 10-volume series learning to play the saxophone and wanting to become the best saxophonist in the world.

Yes, you get the usual monsters and superheroes, too — loads of them — but it is the way manga also plunges you into unspectacular territories, and how it deals with everyday subjects, that makes it so culturally impressive. Its ambitions to teach and change and understand are tangibly different from the usual comic-book models. To star in a manga, you don’t have to slay dragons or breathe fire. You can play football or rugby or learn the piano or be very shy or wish your mother was still there. Manga has become ubiquitous in Japanese daily life precisely because daily life is so often its subject.

And, of course, it’s so brilliantly and adventurously drawn. The range of pictorial invention on display here is staggering. From Toba Sojo’s gesticulating 12th-century frogs to Kuniyoshi’s brilliantly simplified 19th-century whale to Studio Ghibli’s transformed parental pigs in Spirited Away, the Japanese approach to mark-making seems always to have been far ahead of its time. And on this evidence, it always will be.

Manga, British Museum, London WC1, until August 26