Like all life’s profound pleasures, looking at art is a complex business. More accurately, perhaps, it’s a pleasure with many layers and stages. It’s like making love. Sure, you can have a version where it’s a quick in and out, and that’s it. But for the experienced art lover the real joy is in the build-up, the delicious journey, the fabulous pay-off.

But you know that already. It’s what life has taught you, if you’ve been paying any attention at all. Getting the most out of going to galleries, looking at paintings, involves a determination to go deeper.

Of course, the “I don’t know much about art but I know what I like” approach can satisfy the half-hearted. But who wants to eat spag bol from a tin when you can have a tasting menu at the Fat Duck? To help with the preparation I’ve put together a list of five rules to follow. Some may seem contradictory but, as I said, there are many layers to looking at art. So start with the basics.

Decide quickly

In other words, trust your eyes. The visual arts are not called the visual arts for nothing. Art is made to be looked at. And when your eyes decide whether they like something or not, they are drawing on the experience of a lifetime. Your lifetime. So trust them when they whisper their first impressions.

But this does not mean that liking art is an instant or shallow or disposable experience. It isn’t. The more you know, the more you see. What will never change, what should never change, is the importance of first impressions. Again, it’s like love. When you first see someone, do you fancy them? If you do, there’s a chance.

Why do so many people adore Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (above)? Because the moment you see them they feel uplifting, joyous, happy. For 99 per cent of humanity the sunflowers are instantly pleasurable. Why are they instantly pleasurable? Because they prompt your eyes to remember the colour, mood and joy of a sunny day. The “Vincent” on the vase is the blue of a summer sky. The yellow of the flowers is the yellow of a gorgeous field of corn. Your eyes recognise it instantly. And they instantly start sending messages to the rest of you: this is nice.

Do some homework

Trusting your eyes and deciding quickly is a good opening ambition to have with art, but it will only work to a certain point. Back in the arena of love you can fancy many people, but fancies mean nothing if they lead nowhere. What works, what counts, is what happens afterwards. And that’s where putting in the work pays off.

Just as you will never run the 100 metres in 10.2 seconds if you don’t train your legs, so you will never get good at looking at art if you don’t train your eyes.

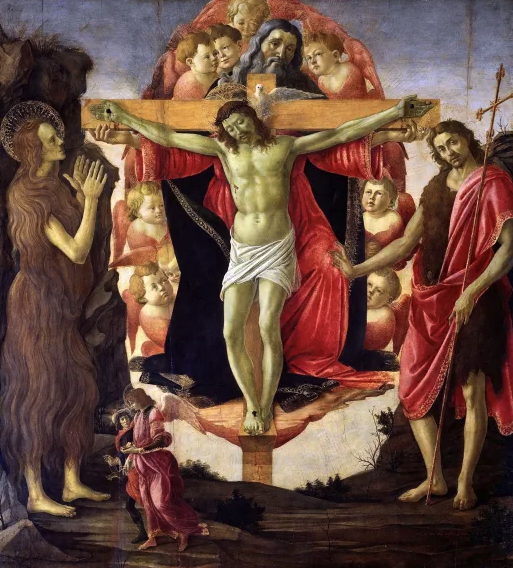

Take this Botticelli, The Trinity with Saints Mary Magdalen and John the Baptist, painted in 1491-94 (above). It’s on show at the Courtauld Gallery in London. And although your eyes will probably recognise its quality and that famous elegance of his, you may be tempted to hurry past because you haven’t got a clue what’s going on. That’s obviously Jesus in the middle, but who the hell are the rest of them? Lots of saints bring lots of confusion.

However, if you learn that the furry figure on the left is Mary Magdalene, the reformed prostitute who changed her ways and paid for her sins by starving naked in the desert protected only by her abundant hair, and that the painting was commissioned by a fraternity of nuns in Florence who helped to save prostitutes, you begin to see where the Hairy Mary comes in. And perhaps you want to find out about everyone else in the picture. So the mysterious Botticelli starts to grow in stature and interest.

Listen to your heart

Your eyes may be the most important organ for looking at art, but the heart runs them a close second. When we look at a painting we look at somebody’s message, sent to us not in a bottle but in a picture or a sculpture or a fresco. Not all those messages are deep. But often they are. Otherwise why bother sending them?

One heart — the artist’s — is trying to speak to another — yours. And if you welcome that message and respond to it, you are making two people happy. The artist and you.

Which brings us to Thomas Gainsborough and his gorgeous, soppy, delicate and emotional portrayal of his two children, The Painter’s Daughters Chasing a Butterfly (above). The first thing to feel is, of course, the artist’s love for his little girls. To my eyes, it’s entirely unmissable.

The two girls, their faces recorded with so much insider knowledge, are chasing a butterfly. But the butterfly has landed on a thistle. When they try to grab it, they’ll be pricked. So a soppy daddy hasn’t just painted his affection for his daughters. He has also painted — and this is where the heart comes in — his fears for them. A sense of uncertainty. A doubt about their future.

I may be feeling this more deeply than you because I too have two little daughters. So it’s almost as if Gainsborough is speaking directly to me. But he isn’t. He’s speaking to the heart. And we all have one of those.

Be an “action viewer”

This is Jackson Pollock’s One: Number 31, 1950 (below). It hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a gallery filled with so many progressive masterpieces it’s the place to go if you want to grow out of the “My child of four could do that” phase of art appreciation and train yourself to look at modern art more helpfully.

Pollock is a good place to start because everyone thinks dripping paint in loose swirls and patterns is easy, when it really isn’t. Lots of crooks and cheats have tried to fake Pollock. Not one of them has managed to do it convincingly. Just as each of us has our own fingerprint, so every artist has their own touch. Recognising that touch requires attention, engagement and, in this case, movement.

One: Number 31, 1950 is 18ft wide and 9ft tall! It’s an absolute whopper. To look at it properly it is not enough to stand still and gaze at it from the distance. Pollock was called an “action painter”. His pictures were made on the move with flows, drips and splatters of liquid paint. To keep up with him you have to move as well. Go up and down the picture. Feel its rhythms. Let it suck you in. Do it with an open heart and you will be transported.

Be impressed

If all you judge art by is your own level of competence or understanding, then you’re looking at art though a blindfold. The really good artists are really good for a reason. They’re better at what they’re doing than you can ever be.

Instead of limiting your appreciation to what you like, expand it to include what many others have liked before you. Here’s an obvious example: Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire (above). First exhibited in 1839, it’s probably his most famous painting. The old boat, being towed to the dock to be scrapped, is packed with significance and symbolism about a lost life and the end of the road. It’s deep stuff. But the thing I’m going to major on is the sunset.

Everybody loves a sunset. All of us have sat at some point beneath a red or orange or purple evening sky and been flabbergasted by the beauty of it. Most of us would love to be able to paint this divine drama. But we just don’t have the talent. Turner did. Just look at the power, the intensity, the volcanic brilliance of his depiction.

In other hands, a painted sunset can look kitsch. In his hands, it’s recorded perfectly. Turner’s greatness should make us humble. And humble people don’t say, “I don’t know much about art but I know what I like.”