Sometimes in art, people disappear. In their lifetimes, they are celebrated, famous, influential, but after they die, fashions change and they slip down the back of the great art sofa in the sky. It can happen to the mightiest talents. It happened to Caravaggio, Vermeer, even Rembrandt. Forgotten for centuries, they needed to wait to be remembered. It’s what happened as well to Georges de la Tour.

Looking at his art today — the irresistible night pictures, the flickering candles, the haunting moods — it’s difficult to imagine him ever being overlooked. But the gods of art love a circuitous route and arranged for his life and career to be filled with unusual amounts of mystery. Born in 1593 in an obscure corner of Lorraine in France, he led an obscure life, painted a lot of obscure pictures, most of which have obscurely disappeared, and died obscurely in 1652. That’s pretty much all we know about de la Tour.

To its credit, the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris (a fabulous old master destination with its own issues with obscurity) has avoided the trap of seeking to fill in the countless gaps. Instead, it has contented itself with bringing together as many rare de la Tours as it could persuade possessive owners to lend, and arranged them in a thrilling journey into the night. A mysterious painter is being allowed to have a fabulously mysterious impact.

The show avoids chronology. It has to. He had a long career but no one knows for certain what came where. He must have been busy, but only 40 or so pictures survive. So every example gathered here feels precious.

We begin with a room that he shares with a couple of his contemporaries in an attempt, I presume, to give him some context. Unfortunately, the chosen contemporaries, Jean Leclerc and Mathieu Le Nain, are immediately blown out of the water by the art on the other side of the room.

The key difference is in the lighting. Leclerc and Le Nain have also set their action in the fashionable darkness that Caravaggio introduced into art and which spread like wildfire across Europe, but where their darkness appears stagey and effortful, de la Tour’s is immediately exciting, gripping, thrilling. He’s the light, we’re the moths.

Job Mocked by His Wife shows the biblical patriarch, whom God is testing by taking away his wealth and making him ill, being chastised by his wife, who looms over his shrivelled body in a robe of glowing red, illuminated spectacularly by a flickering candle. What counts here is the magical mood into which we are being plunged: the sense of intimacy and thoughtfulness that glues us to the picture. Job is so shrivelled and pathetic. His wife is so looming and symbolic. Although we are technically in the big world of the Bible, it feels as if we are somewhere modest and true, somewhere on our side of the story.

Unexpectedly, I was reminded of Vermeer and his mysterious moods: that sense you get with him of never knowing the full meaning of his work, but immediately feeling its hold. Like Vermeer, who was also forgotten when art grew pompous and began insisting on classical values, de la Tour speaks human to us, while those around him seek to lecture us in Greek.

Ooops. There’s a lot of the show to go and we haven’t even left the first room! The exhibition ahead tries here and there to add more context to the de la Tour story and, very interestingly, it has a go at expanding our image of him by including a clutch of excellent contemporary copies. Some of which — St Francis in Ecstasy from Le Mans, St Sebastian Treated by Irene from Orleans — are so good and look so right I would be tempted to promote them to autograph works if I were the curator.

The copies serve also to challenge the image of de la Tour as an isolated and quirky outsider. If this many people were copying him then he had to have been in big demand. Indeed, no less a personage than Cardinal Richelieu commissioned one of the marvellous pair of St Jeromes that can be seen flagellating themselves with bloody vigour in another of the show’s highlights. De la Tour, we learn, became so successful he worked for the French king.

Another effort the show makes is to recognise the quality and range of his daylight pictures. The candle scenes are so unstoppably alluring they have overshadowed a significant portion of de la Tour’s surviving output, which stays in the light and gives us a curious portraiture of standing figures and characterful types: hurdy-gurdy men and the like. With their clumpy shoes and perfectly creased aprons, they form a gnarled cast that repays your slow attention almost as fruitfully as the night scenes: almost, but not quite.

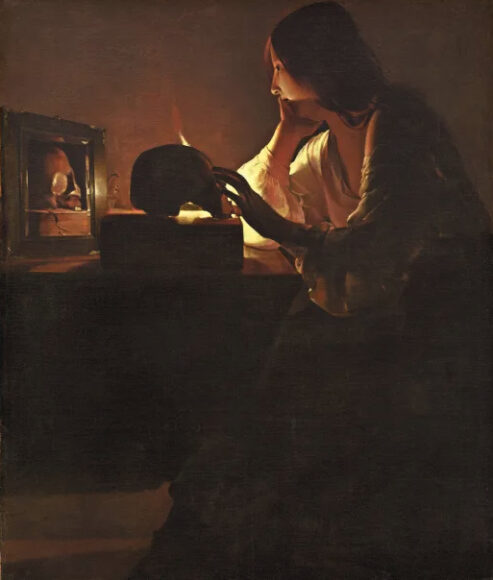

In the end, the place to gorge yourself at this gorgeous event is in front of the 20 or so signature candle scenes that pop up at teasing intervals: the magical Mary Magdalene staring into a doomy reflection of a skull; the lovely Holy Family oozing huge religious warmth and featuring the cutest swaddled baby in art.

In a poetic nocturnal language unmatched by anyone, de la Tour keeps making clear that he is one of our greatest artists. It’s so obvious, you really do wonder how it could have been missed.

Georges de la Tour is at the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, to Jan 25