Environmental issues are the trendiest subject in art right now. The climate. Ecology. What we’re doing to the planet. Everybody is tackling it. And they’re doing it badly.

Re/Sisters at the Barbican is essentially a giant PowerPoint presentation packed with jargon and clunky curatorial interjections, masquerading as an art show. The Serpentine Gallery’s Back to Earth programme probably means well, but all it serves up is dollop after dollop of blather and obfuscation. The Frieze Art Fair, which landed recently in Regent’s Park, next to London Zoo, lectured us busily on climate matters while remaining satanically blind to the size of the gigantic carbon footprint it was leaving behind with its electricity-guzzling, Earth-murdering, private jet-enticing marquee madness.

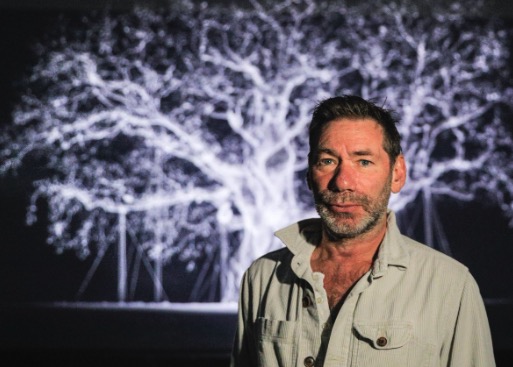

So what a joy — what a relief — to see the territory being explored as inventively and sentiently as it is by Mat Collishaw in a subfusc display at Kew Gardens. The home of British botany has given over a key exhibition space to Petrichor, Collishaw’s arboreal lament, and he has repaid it with one of the shows of the year.

Best known as a member of the Freeze generation — that’s Freeze as in Damien Hirst’s pioneering 1988 student show, not Frieze as in money-sucking tented nightmare — Collishaw has loitered on the fringes of the British art world, never being given the recognition he deserves. His art pops up in surprising places — a guerrilla strategy that makes him aesthetically independent and especially inventive.

The Kew show begins with something visually miraculous: a set of famous watercolours of wayside plants by the German genius Albrecht Dürer that Collishaw has somehow persuaded to sway gently, as if a puff of wind is blowing across Dürer’s minutely observed Renaissance botany. The miraculous movement has been achieved with advanced computer technology, but the best thing about these delicate depictions of clumps of everyday horticulture is that their presence remains so quiet and unassuming. State-of-the-art electronics have somehow achieved a soothing botanical peacefulness.

Visitor beware. The restful watercolour illusions lure you into hopeful moods that are about to be shattered. In his next moment of advanced technological artistry, Collishaw sends us on a journey through the history of plant collecting — it does not end well.

The reason you and I can buy spectacular succulents in our local garden centre is because the Victorians invented a device called a Wardian case that enabled the transportation of live plants to Britain from distant continents. In a spooky piece of postlapsarian animation, Collishaw takes us on a journey that starts with the transportation of a cornucopia of exotic plants to a faraway island, and ends with the island smouldering as the fires of horticultural damnation complete their vengeance. The spooky animation is brilliantly achieved. The doomy symbolism hits a nerve. But what’s really impressive is the range of scholarship being displayed, and the independence of vision. The focus on the Wardian cases is as unpredictable as it is effective. Where Re/Sisters angrily shouts curatorial clichés, Collishaw’s environmental despair is grounded in deep research, and expressed with the poetic invention surely we ought to expect of all good art.

Having yanked us on to a bleak path, the show grows murkier as it burrows deeper into the true story of plant life. Where most of us coo happily in the presence of a beautiful bloom, Collishaw has studied his way to a darker understanding of the horticultural wars.

“Red in tooth and claw, plants compete in an unrelenting struggle for survival and dominance,” he explains in one of his helpful wall texts in a gallery filled with flowers — painted and sculpted — that feel as if they have inherited their colour schemes from a genus of venomous snake. So bright. So toxic.

What becomes evident is that the story of plants is intended here as the story of another especially murderous Earth species: us. In an imaginative leap that surprised the hell out of me, but rings true, Collishaw begins drawing parallels between the showy need of plants to be noticed and pollinated, and human behaviour in the internet age. The exaggeration of self that has been such a ceaseless feature of human interaction on social media is compared with the determination of the plant to be spotted.

It’s an idea expressed most stirringly in a contraption called The Centrifugal Soul, a modern version of a zoetrope: another Victorian device, one that creates the illusion of movement. In this case, the crude animation technique confronts us with a ring of hovering hummingbirds pecking away at an assortment of enticing blooms that open and close to accommodate them. Just as we attention-seekers pile on to TwiX and Instagram, clamouring to be noticed, so the flowers in The Centrifugal Soul are locked in an endless contest of floral allurement.

The message that humans are spoiling the natural world with our greed and animal nihilism seems constantly to be implied. In Albion, a ghostly hologram of the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest, an 800-year-old tree with Robin Hood connections, turns slowly into a dark skeleton. A sweaty little film, set in the near future, shows the National Gallery overrun by invading weeds climbing all over the Guido Renis. In an especially tricky use of internet technology, a set of NFTs invites buyers to invent their own gorgeous blooms. No one mentions genetic manipulation and its toxic consequences. But the lurid flowers people come up with feel immediately like an illustration of it.

What a relief to see prickly environmental politics fertilising art so cunningly and imaginatively, rather than having them blasted dumbly at us by artless curators.

Mat Collishaw: Petrichor is at Kew Gardens until April 7