I know what I want to get Nicole Eisenman for Christmas. A copy of The Power of Discipline by Daniel Walter. Even a brief perusal of this helpful tome will make clearer why the artistic career presented to us in the Eisenman retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery ends up as such an evident descent. And why the absence of a clear path through the torrent of art is a problem. Being an artist and going wherever you fancy are not the same thing.

Celebrated today as a heroine of the American sex wars, Eisenman was actually born in Verdun, France, in 1965. Her father was a US army psychiatrist and her mother an environmental planner. Both of them make cameo appearances in paintings in the Whitechapel show, the father at a psychiatric session with Nicole on his couch, and the mother at the head of a traditional Jewish Seder meal on the eve of Passover. The catalogue tells us there was art in the family, too, with a great-grandmother who was a painter.

In 1969 the Eisenmans moved to Scarsdale, New York, and that, I imagine, is when the abundance issues began. The opening sight in the Whitechapel retrospective is a wall covered — plastered — with scores of drawings made in the 1990s celebrating Eisenman’s unchained lesbianism.

In Alice in Wonderland, from 1996, little Alice, her head obscured by a lady garden, performs cunnilingus on Wonder Woman. In Betty Gets It, a parody of The Flintstones, a naked Wilma mounts a naked Betty. In Nice Smell Babe, Charlie the Tuna sniffs the buttocks of a generous nude and compliments her on her aroma. None of this cartoon twaddle offends me on decorous grounds. Eisenman enjoying her sexuality with such evident enthusiasm is par for the course for 1990s New York and fun to watch. As art it’s energetic, tingly, provocative. Less appealing is the giggly American dumbness of it all: the sense that the art education being evidenced here consisted chiefly of reading trashy comics.

Thus that fascinating painting in the Louvre of Henry IV’s royal mistress, Gabrielle d’Estrées, having her nipple tweaked by her sister, a mannerist allegory celebrating Gabrielle’s fertility, gets a cartoon makeover here with the word “SLUT” scrawled in lipstick colours across the sister’s chest. Perhaps an even better Christmas present for Eisenman would be A World History of Art by Hugh Honour and John Fleming? It’s a thoughtful introduction for grown-ups.

The start of the show, with its bouncy comic book lesbianism and its painted tales of angry Sapphos hunting down men, castrating them and eating them, turns out to be its liveliest stretch. A new voice has appeared in art and is enjoying itself with brash American confidence and a fresh tranche of subject matter.

Less convincing are the effortful attempts at seriousness that begin now to pop up here and there. Having had its decade of fun, Eisenman’s art begins to develop weighty ambitions. And the cartoon education she has enjoyed so far isn’t sturdy enough to carry them.

The Session, the painting of her father psychoanalysing her on a couch, is too clumsy in its jokey borrowings to be edgy or poignant: dad and daughter feel as if they belong in separate comic strips. The painting of her mother presiding over the Passover meal crowds too many ill-fitting portraits around the table to be compositionally effective. Eisenman’s recurring weakness — the absence of an edit button — is increasingly evident.

Although she is chiefly renowned for the huge political allegories that begin now to tempt her, the best art from the second phase of her career are the works in which she goes soppy on us and admits to feelings of love and warmth. Sloppy Bar Room Kiss, from 2011, shows two women slumped in a boozy embrace in a late-night dive: their evident tenderness sucking the bleakness out of the surrounding squalor.

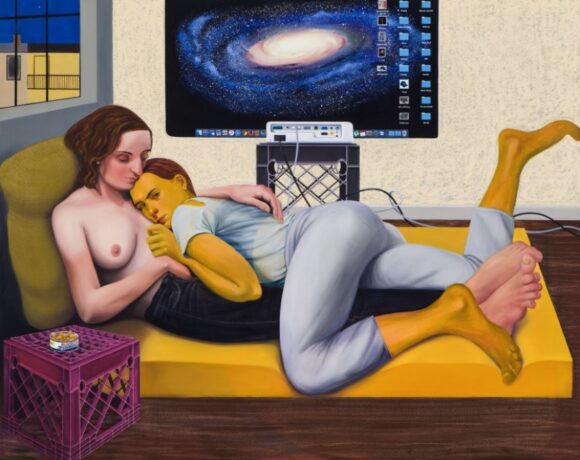

Morning Studio, from 2016, shows two women on a mattress, entwined lovingly in an intimate knot. They’ve been watching a movie. It’s finished. Now it’s just them, us and a palpable sense of big city isolation. Something tangible is being expressed, and it’s being done movingly.

Unfortunately, Morning Studio marks the end of the good news in this effortful retrospective. Feeling the need to be weighty rather than true, Eisenman produces a clutch of flat, cartoonish paintings that the captions tell us are intended as a comment on the screens on which we now depend with our computers and mobile phones. The jokey imagery grows increasingly — and unconvincingly — imitative of Philip Guston as it seeks to brand us as dumb beasts addicted to pixels.

Worse is to come when she turns to sculpture. Why didn’t anyone stop her? A room filled with ponderous approximations of heads, made crudely from aluminium, clay and bronze, is explained by Eisenman’s quip: “When you can’t think what to draw, draw a head.” This is the level to which we have descended.

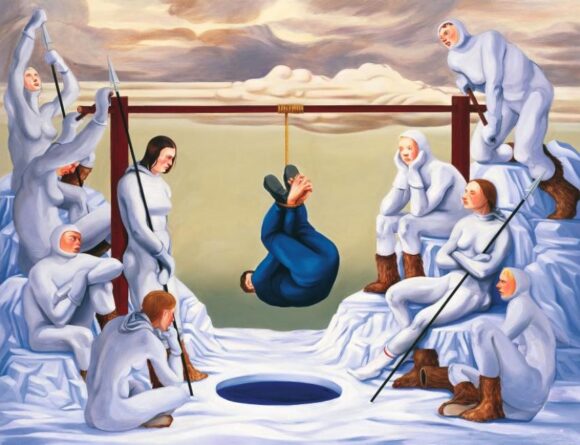

The paintings she continues to produce are increasingly weak and increasingly big. Most recently, the suite of huge anti-Trump works she has been churning out have their hearts in the right place, but the politics in them is doing all the heavy lifting. As art, they are clunky fails.

Heading Down the River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass, from 2017, shows a boat, shaped like the jaw bone of an ass, speeding towards a waterfall while a pied piper on the bow leads the vessel to certain destruction. It’s such a laborious attempt at national symbolism.

Hilariously, the final work here, a gigantic painting of a crowd of metrocentric New York protesters in City Hall Park, hanging out, puffing uncool fags, is so big the gallery could not afford to bring it over. Instead, it’s represented by a giant photocopy! Thus a spoilt show achieves the perfect spoilt ending.

Nicole Eisenman is at the Whitechapel Gallery, London E1, until Jan 14