Was Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) a fascist? I ask the question because the Morandi exhibition, which has arrived at the Estorick Collection in north London, does not — the paperwork for the event could hardly be more gushing or unquestioning — but also because devotees of Morandi’s art seem to find his work so angelic. Perhaps they need reminding of his problematic past.

“The great faith I have had in fascism from the outset has remained intact even in the darkest and stormiest of days,” Morandi wrote in an autobiography he published in 1928. “I tend to be solitary by temperament and for artistic reasons. This in no way derives from empty pride or any lack of solidarity with all those who share my faith.”

Of course, being a card-carrying Italian fascist in 1928 was not the same as being a true believer in Munich in the same year. Italian fascism was tangibly gentler and more inclusive than its Nazi counterpart. Also, 1928 was nearer the start of Morandi’s career than its end. But having some awareness of the dark underpinnings of his “angelic” vision seems to me to be crucial to an informed understanding of his work. I bring up his fascism not as a disqualification, but as a corrective.

That done, let’s get in there and see what the King of Beige has for us in a selection of his paintings and prints borrowed from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, a private museum near Parma founded by Luigi Magnani, the son of a dairy farm magnate who devoted his inheritance to art. Magnani, who I think we can say with some confidence was not a socialist, transformed his home into “the Villa of Masterpieces”, filling it with pictures by Titian, Dürer and Goya as well as 50 works by Morandi.

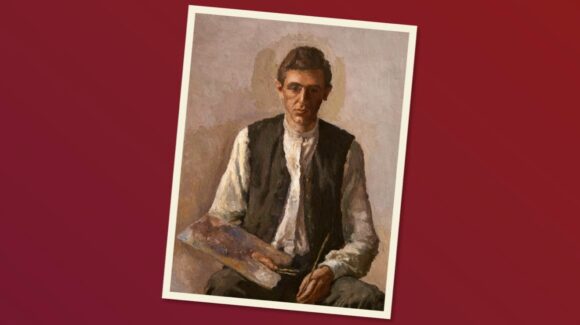

Unexpectedly, the first example here is not a painting of a bottle or a jug, but a self-portrait. Apparently, Morandi painted several of them in a career devoted so notoriously to still-lifes. This one, from 1925, is said to be the best. Heaven knows what the rest are like.

We see a forlorn figure, dressed in a brown waistcoat and a baggy white shirt, set against a beige background. His trousers are brown. So is his hair. He holds a palette with two colours on it: brown and white. Unusually, the painter does not look out at us from this symphony in beige. Instead he stares morbidly down at the floor as if remembering the death of his mother. If ever a man looked badly in need of some jelly and cake, it’s Giorgio Morandi in 1925.

The studied glumness of the self-portrait sets the tone for events ahead. The pose has been borrowed from Watteau’s great portrayal of Gilles the clown, but where Watteau gave his delicate Pierrot a universal air — there but for the grace of God go all of us — Morandi’s thick and showy misery feels self-referential and claustrophobic. It’s obvious, too, that he’s not very good at painting figures. So he turns instead to bottles and jugs. Not immediately, though. As an intermediate step, we watch him struggling with a bowl of apples and pears. It’s intended as an homage to Cézanne, but the sludgy paintwork leaves the colours looking as if they’ve been dropped in the mud.

The same happens with an adjacent still-life of some musical instruments, which, the caption tells us, was commissioned by the music-loving Magnani; the only such commission Morandi ever accepted.

Unable to work with Magnani’s chosen instruments, Morandi bought a toy guitar in a flea market, found a discarded mandolin in his attic, and painted those instead. The results are so stiff they look like the handiwork of a Sunday painter: the Italian Alfred Wallis.

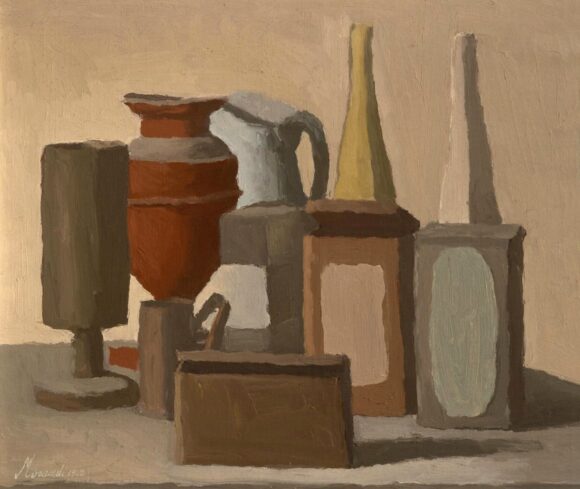

In Italian, a still-life is called a natura morta, which means “dead nature”. It’s a description that fits what we have seen so far. We are watching a limited artist, rifling through a stack of old master influences — Chardin, Watteau, Cézanne — in an effortful search for his own path. Half way along the first wall he finds it.

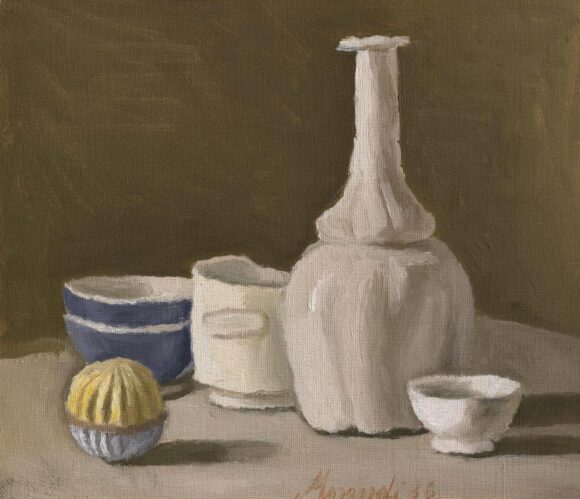

A typical Morandi — and there are a lot of them; he was prolific — will show a couple of bottles, a jug, a sugar bowl and a chipped cup gathered glumly on a table like a band of street urchins in one of Murillo’s beggar paintings or the alley gang in an episode of Top Cat: there’s a tall one, a fat one, a thin one, a small one. It’s almost impossible not to anthropomorphise the raggle-taggle gang of bottles and give them human airs.

As his passion for Chardin fades and a passion for Vermeer grows, the colours of the bottles lighten, and the atmospheres in his art grow more pearly. We see him becoming freer and more fluent. What we never see is him cheering up. The moroseness of the early self-portrait never flees.

Where, you may be thinking, does the fascism fit in? On a superficial level, it can be understood, I think, as a deliberate turning of the back on European modernism, with its air of Parisian decadence and its march towards abstraction. On a deeper level, we are watching a call to order, a specifically Italian search for the formal strictness and faded glory of Piero della Francesca and the Italian primitives. File under “Nostalgic”, perhaps, rather than “Sinister”.

Giorgio Morandi is at the Estorick Collection, London N1, until May 28