To prepare myself to see Spain and the Hispanic World at the Royal Academy, I did that thing psychologists advise where you write down the first words that come into your mind.

As an aficionado of Spanish art, spewing the words was easy. I closed my eyes and out they poured: “Dark, passionate, exciting, Catholic, scary, dramatic, raw”. That’s the art of Spain. A moment later “Carmen” also popped out.

The show is a “greatest hits” selection of art, objects and books from the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, the controversial New York institution founded in 1904 by the wealthy “philanthropist” Archer M Huntington. Having developed a passion for Spanish culture, Huntington dreamt from an early age of creating a Spanish museum. Using his folks’ cash, he began collecting in his twenties, and by his mid-thirties had amassed enough Iberian produce to found the Hispanic Society of America.

This posh but rather doomy museum in upper Manhattan has been closed since 2017 for an extensive rebuild. It is finally due to reopen this year, and in the meantime has sent a selection of its most prized possessions around the world on a money-raising tour that has now arrived in Britain.

When I reached the event’s end, I tried the psychologist’s trick again. My new list read: “Polite, nice, coffee-table, pale, Wasp, moneyed”. With “coffee-table” underlined. Yes, there are marvellous things here. But the overall effect is luxurious and tepid.

We commence with a skip through the first three millennia of Spanish culture that takes us from the Bell Beaker potters of c 2400BC to the Visigoths of AD600 via the Romans of AD140, in one room. The thin smattering of objects that seeks to illustrate this vast journey achieves nothing tangible. The Visigoths, who ruled Spain for three explosive centuries, are represented by a single timid belt buckle.

The Islamic invasion of Spain, which began in AD711 and lasted until 1492, is treated to a tad more detail and a richer selection of “treasures”. Notably, a gorgeous wall of dishes decorated with sparkling gold lustreware. But here too the absence of scholarly documentation and truly helpful captions robs the objects of a meaningful context. You go “Oooh”, you move on.

At the heart of the journey, in the largest and grandest of the Royal Academy’s galleries, sits a selection of the Hispanic Society’s finest holdings. And even a visitor as curmudgeonly as me can have little to complain about in this Aladdin’s cave of books, paintings, textiles and objetos de arte. It includes no fewer than three portraits by Velázquez, especially one of a little girl, probably a family member, observed so precisely and with such tangible intimacy that it alone is worth the entrance fee.

Joining it are a couple of good El Grecos; a spectacular hoard of Catholic bling fashioned from the gold flowing into Spain from the new American colonies; and some impressive manuscripts, notably a 15th-century Book of Hours, written in gold on black parchment, one of only three known examples of this strange gothic technique. Huntington was particularly interested in Spanish bibliophily. Nowhere does this event feel more in need of depth and context than in its presentation of his pioneering literary accumulation.

Created at a time when American attitudes to Spain were themselves the attitudes of a conquistador, the Hispanic Society Museum has in recent years come in for persistent criticism of its mindset and its past. The collection has been accused of over-favouring “Old Spain” and of forgetting the sins of the Spanish invaders and their subjugation of the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas. In today’s art world, such accusations can no longer be ignored. One of the reasons the museum has been closed for five years is so that its displays can be updated to reflect the present thinking on Spain’s American past. This show cannot avoid such matters either, and, having dazzled us with its best treasures, it begins a light examination of Spain’s colonial impact that lasts for several rooms.

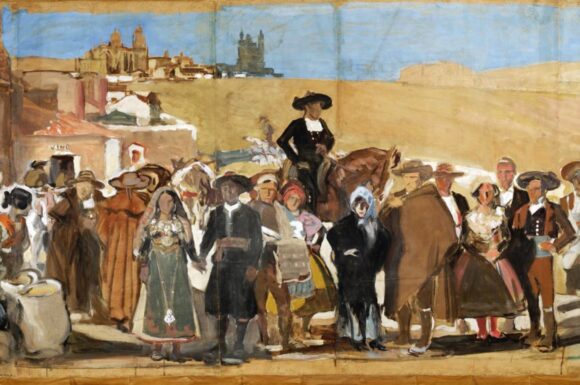

We see the first hesitant maps of the Americas produced when no one was yet certain of the continent’s outlines; pictures and sculptures painted and carved by indigenous artists re-educated in the Spanish way. What we don’t get is a sense of the true horror of conquest; the cruelty and violence of the Dominican missionaries; the eschatological madness that underpinned the invasion of the New World. All this is missing.

Fortunately, along comes Goya, with his prickly moods and his untameable vision, to knock the show off the coffee table for a moment with a ring of accusatory watercolours and his peculiar, ambiguous, looming portrait of the Duchess of Alba, dressed from head to toe in flirtatious black, pretending to be a maja, a showy belle of the lower classes. Why is she pointing to the sand at her feet where the words “Only Goya” have been scrawled? Why the smouldering? Why the erotic charge? No one asks. No one answers.

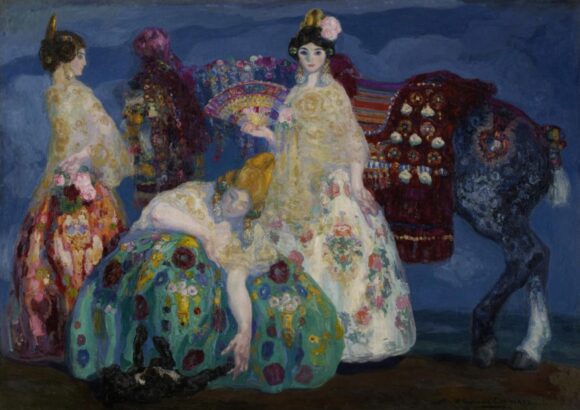

Goya done, we skip quickly back on to the coffee table, with two sunny rooms devoted to the belated impressionism of the overrated Joaquín Sorolla. But not even two rooms of Sorolla can immediately soothe the scorpion sting of Goya.

Spain and the Hispanic World is at the Royal Academy, London W1, until Apr 10