Unfortunately the results of these effortful marriages are usually disappointing and sometimes horrendous. I will go to my tomb squirming at the memory of what the Belgian grave robber Jan Fabre did to the Hermitage in St Petersburg in 2016 when he placed his stuffed crows and heavy metal vampire art in front of the Rubenses and the Leonardos. It was so awful I left for Moscow.

To be fair to our own National Gallery in London, it has a decent record in this problematic pursuit. In 1990, at the start of the trend, Paula Rego proved to be a genuinely worthy visitor when she was made its artist in residence. More recently George Shaw, his eye for detail sharpened in the banal suburbs of Coventry, responded interestingly to the historic collections. Now, by inviting in the American painter Kehinde Wiley, the National has hit the jackpot. What a potent and stimulating event.

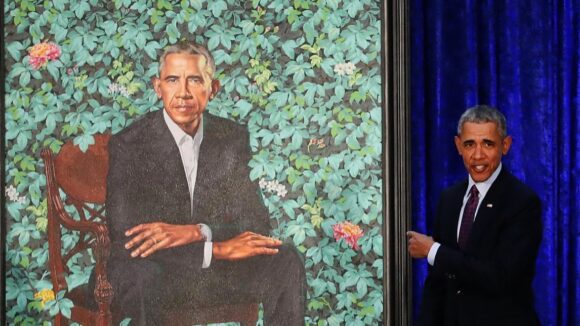

Wiley is best known for his portrayal of Barack Obama in 2017: a black artist painting a black president. I can’t say the results were overly impressive — Obama appeared to be sitting in the middle of a hedge — but they blasted Wiley into our consciousness as an artist on a mission. A year later he popped up at the National Portrait Gallery with a garish portrayal of Michael Jackson riding a rearing stallion in the manner of Napoleon crossing the Alps. Here, clearly, was an artist seeking to shift ideas of heroism from a white platform to a black one.

It’s an effort that continues with The Prelude, a dramatic two-parter involving a cluster of paintings and a film in which Wiley wades into the heroic landscape tradition of western art — think JMW Turner, think Caspar David Friedrich; think mountains, avalanches and stormy seas — and sets about stealing it for the other side: turning white into black. So striking is the alchemy, so tactile and insistent, that by the time he concludes his efforts we are left with a genre that can never again be what it formerly was.

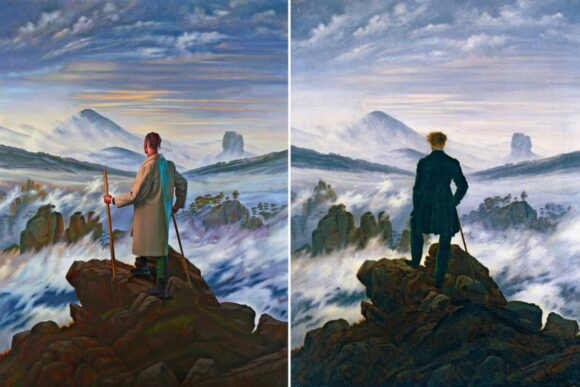

The transformation begins with paintings. Taking as his model a couple of Friedrich’s most celebrated pictures, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, from 1818 (bloke in frock coat gazing out from the top of a mountain), and Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, also from 1818 (two blokes and a woman on a looming cliff with an endless sea before them), Wiley thrusts powerful complications into the imagery by swapping the white cast for a black one.

He does it on a cinematic scale. The original Friedrich paintings are tiny compared with Wiley’s Imax-sized reworkings. In his giant version of Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog the figure with his back to us looking out across a seemingly endless expanse of white is now a young black man from Dakar, standing on the top of a mountain with his hiking poles while the snowy landscape stretches before him in every direction: it’s the impossible terrain, you feel, he needs to conquer.

All this is painted with a dazzling photorealist technique that gives everything it tackles the urgency of a movie shoot. The dreamy nostalgia of Friedrich has been replaced by something active, vivid, up to the minute. This isn’t just an update of the old masters, it’s a yanking of them out of the past and a thrusting of them into the present.

While the general direction of Wiley’s ambition is clear — he’s claiming a territory for black art that had previously been denied to it — the specific meanings of the reworked landscapes are tougher to grasp.

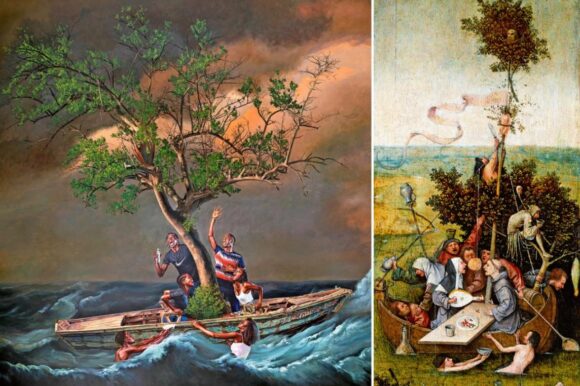

Across the room from the Friedrich mountains is a cluster of seascapes inspired by Hieronymus Bosch’s famous picturing of the Ship of Fools. In the Bosch a shipload of fools who know nothing about sailing is attempting to cross the ocean on a wonky boat with a tree for a mast. They fall overboard, they argue, they’re doomed not to make it. By changing the doomed cast from white to black Wiley reverses the image’s traditional meaning and transforms it into a contemporary survival scene. Suddenly we are looking not at doomed fools but at doomed refugees; and the slap, slap, slap of the slavery ships becomes audible.

The show’s title, The Prelude, comes from William Wordsworth’s most celebrated poem, where his glum vision of life as a circular journey in which we eventually arrive where we started found its finest form. Wiley’s paintings, dramatically presented in a cinematic twilight, take Wordsworth’s hopelessness and give it the Netflix treatment: quickening its pulse, making it urgent.

The opposite happens in the beautiful and soulful film, also called The Prelude, that completes the show. Lasting 30 minutes, this slow-burning drama in the snow stars a cast of black wanderers — old, young, men, women; all amateurs, all recruited in the streets around the National Gallery — who have ended up at a Norwegian fjord in the winter, where their unexpected blackness is measured against the blanketing white. They smile, they play games, they withstand the cold, but the world that surrounds them can never be theirs. Until, at last, they build a fire and its magical sparks light up the sky.

Packed with memorable cinematic moments — the combination of a blanketing white nature and characterful black faces is a recurring winner — the film keeps prompting imaginative digressions. I found myself remembering that we are all descended from the wandering African, and that one of the things the show is about is the faraway places we ended up. You can’t get much further from sub-Saharan Africa than the frozen fjords of Norway.

So it’s an event that makes you think and keeps you thinking. Technically, with its trompe l’oeil wizardry, it is a masterclass. With its new moods, new ideas, new promptings, it’s a bucket of water thrown into the faces of the sleepy old masters.

Kehinde Wiley: The Prelude is at the National Gallery, London WC2, until Apr 18