The gods must be fans of post-impressionism. They must love Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, Seurat, Toulouse-Lautrec. How else to explain the timescale that has governed the closure and reopening of the Courtauld Gallery, Britain’s finest collection of post-impressionist art?

Consider the sequence. The gods send down the Covid crisis. It messes up the plans of every gallery in the country. Except the Courtauld, which had just closed for a big rebuild. While all the other galleries were dealing with crippling closure issues, the Courtauld continued as planned. Now, with the coast relatively clear, it has reopened. Simples.

I am not generally a fan of big gallery rebuilds — they are too often driven by vanity, fashion and directorial egotism — but the Courtauld definitely had problems. The pine flooring put in at the last rebuild made it feel like a Norwegian sauna. The lighting was unhelpful. The furnishings were clunky and old-fashioned. And the route through the collection made no sense. Squeezed into tight Georgian spaces in an 18th-century corner of Somerset House, it was more of a dodgem ride than a journey of enlightenment.

So there was lots to sort out, and I went along to this week’s unveiling expecting change. What I wasn’t expecting was a complete repositioning of the gallery’s identity and status: a profound rethink.

The two-year restoration cost a few quid short of £60 million. The first signs of it strike you the moment you enter. Where previously there was a sense of clutter, with a ticket desk somewhere in the middle, there is now an airy vestibule that says hello calmly and elegantly. The doorway on the right leads to the gubbins: ticket desk, lockers, loos, café. The stairs in front lead up to the art.

Mounting the stairs at the Courtauld has always had a symbolic frisson to it. The original architecture was determined to make you feel as if you were heading somewhere special — in those days it was up to the Royal Academy, housed at the top — and the rebuild has made this sense of ascent feel more tangible again. (There are, of course, lifts for wheelchair users and mums now).

The first gallery you come to didn’t exist in the old layout. It has been fashioned out of a space in which the security men had their tea. It now displays a selection of early Renaissance art that was previously holed up in a dark room downstairs: Bernardo Daddi’s 1348 Crucifixion with Saints; three predella panels from the 1420s by Fra Angelico; Robert Campin’s gorgeously detailed Entombment from 1425.

These rare fragments from the first moments of the Renaissance aren’t just beautifully displayed, they feel much more present. Downstairs they were difficult to see, let alone love. Now they start you off on a new journey through a different type of Courtauld: a gallery filled not just with masterpieces of post-impressionism, but with all this other stuff as well.

The rearranged galleries, numbered from 1 to 12, have been positioned chronologically to trace a passage from the early Renaissance to the early 20th century. Room 3, where the Van Goghs and Renoirs used to hang, continues the story of the Renaissance’s beginnings. Room 4, where the Cézannes and the Gauguins were, is now devoted to the Renaissance proper, and especially to Botticelli’s great altarpiece of The Trinity with John the Baptist and Mary Magdalene.

I am ashamed to admit that I used to amble casually past this enormous picture without fully realising what a masterwork it is. Newly restored, given pride of place in the room, it stands revealed as one of the great Renaissance altarpieces in Britain.

Thus the new arrangement seeks to highlight works in the collection that were easy to miss, and by doing so enlarge the gallery’s general presence. Rubens, represented by two dozen works, gets a room to himself. The baroque age gets a gallery. The 18th century gets a gallery. Up, up, up we climb, through the annals of art, until we reach the impressionists and post-impressionists at the top.

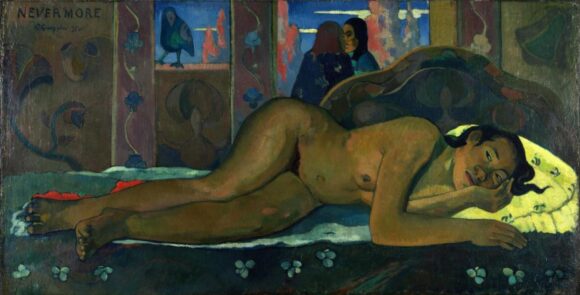

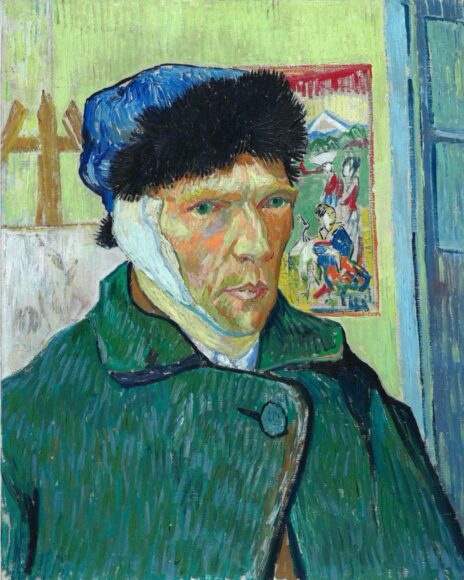

This spectacular hoard, collected by the gallery’s founder, Samuel Courtauld, in just ten years, between 1922 and 1932, is dense with goodies. It begins with a sketch for perhaps the most significant painting of the 19th century — Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. Then come Degas and Monet, and a wall full of superb Cézannes. The Gauguins, especially the haunting Nevermore, are among his finest works. The Seurats are exceptional. The Van Goghs heartbreaking. All this used to be housed downstairs in the central galleries. It has now been transferred to the Grand Gallery at the summit where the Royal Academy used to have its summer show. Lit with real light from above, spacious and airy, coved and uplifting, it’s an appropriate space for a mightily impressive selection of art.

Thus the rebuild is unquestionably a success. It enlarges the presence of the gallery, makes it more comfortable to go round, and lifts the Courtauld a couple of rungs up the museum ladder. Not enough people used to come here. Now they will.

So there’s much to cheer. But not, perhaps, everything. As a sourpuss, I loved the fact that when you went to the Courtauld there was rarely anyone else there. And the old hang, barely changed since the time of Samuel Courtauld, had an individual charm to it.

The new arrangement positions the art more logically but makes some of it feel less exciting. The new gallery is more like other museums and galleries than it used to be. So, yes, a lot has been gained. But a little has also been lost.

The gallery reopens on November 19