It was an American football coach back in the 1950s who made the cheery observation that when the going gets tough, the tough get going. If real life were less like real life, and more like a Clint Eastwood movie, he may even have had a point. But it isn’t. In real life bad times test you rather than toughen you. That’s what’s been happening to our museums.

Covid has caused damage in every walk of life, so why should it have spared the arts. The bug has made it impossible to continue as if nothing had happened. In the process it has forced an assortment of issues into the open. Not all our museums and galleries have failed their Covid MoT, but as the problems rained in on them from so many angles — cancel culture, funding, job cuts, slavery legacies, climate change — all were tested, and most were found wanting.

I say “most” because a couple were already closed or planning to close when the pandemic broke, and have appeared, therefore, to sidestep the scrutiny. The National Portrait Gallery shut its doors in June 2020 for a £35.5 million refurbishment. It was preceded by the Courtauld Gallery, which began a huge makeover in 2018 that ended up costing nearly £50 million. Some will think they were lucky: they have avoided the chaos. Others will note the heaps of Monopoly money being passed about here and ask if the vanity projects were really necessary. It’s not a good look. For the National Portrait Gallery in particular to go missing in action during the greatest public test since the Second World War, so it could build itself a new front door, feels like a dereliction of duty.

That said, the NPG is by no means the biggest spender on museum vanity. That dark honour will belong in perpetuity to Tate Modern, the least impressive gallery of the Covid era. Pretty much everything that could have gone wrong at Bankside went wrong. And making it all worse was the memory of the £260 million spent recently on the Blavatnik Building, a set of doomy concrete caves that have never ceased to feel spectacularly unnecessary. Every time I go in there I feel lonely, scuttling about the looming canyons like a mouse in an aircraft hangar.

In the pre-Covid era growing bigger appeared to be the way to go for the thrusting modern museum. But that changed when the bug hit. In the post-Covid world no one will ever again spend 260 million sacks of noisy money on an unnecessary extension that is also carbon-lethal. Keeping the lifts going at Tate Modern must cost the equivalent of a couple of rainforests a year. The new Heather Phillipson installation at Tate Britain, packed with beeping light shows and giant fields of video, must have claimed a couple more. “What about the planet?” I felt like scrawling on one of its greedy electronic screens.

Covid has recast giant museums and galleries as products of another age. And while the bug has been shining a raking light on the workings of these monsters, showing up their extravagance, it has paradoxically been reminding us why we invented art in the first place. During the lockdowns my Twitter feed was thick with enthusiasts sharing their feelings. Countless mothers of countless kiddies wrote to say how grateful they were for the art that was keeping their offspring happy and busy. Many branded it a lifeline.

But the mismatch of scales in museum land wasn’t all that Covid made obvious. It also shone a light on the awful judgment calls that kept being made. Heavens but they totted up.

Leading the way, again, was the gaffe-prone Tate. The brutal announcement of more than 300 job cuts last summer led to recurring street protests. It wasn’t the jet-setting Tate curators who were sent packing. It never is. Instead, the axe fell on the so-called support staff: the bread-and-butter gallery workers who keep the monster alive.

It wasn’t their fault the empire had grown so unworkable. That was the achievement of the Julius Caesar of museum expansion, the previous director, Nick Serota, who, during his 30-year shift at the helm, had seen a single Tate on Millbank turn into four mega Tates across the land. Serota is now running the Arts Council. For Christmas I’m going to send him Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Such an instructive read.

Similar problems at the V&A were dealt with almost as badly. However, the discarded support staff in this case were joined on the rubbish heap by a generation of knowledgeable curators whose expertise was world famous. In the old days you went to the V&A to discover Japanese or Indian art. Today you go to look at Dior handbags.

Halfway through lockdown the V&A bosses announced that they were closing the National Art Library, to which I and thousands of others regularly repair to top up on our art historical knowledge, for a restructuring. Only the howls of disgruntled library haunters stopped that brutal removal in its tracks.

Which brings us to the ugliest weed that has thrived in the glum, sweaty, shivery conditions of Covid: cancel culture. A few weeks ago Jess de Wahls, a textile artist whose work was on sale in the Royal Academy shop, had her produce removed because some views she had expressed on social media were deemed transphobic. “Out you go,” the RA roared.

Days later, after a torrent of angry reaction in every corner of the Twittersphere, the academy changed its mind and admitted that it had made a hasty mistake. De Wahls had been shoddily treated. Free speech was free speech. “I don’t give a f*** about art institutions,” the excellently insouciant de Wahls countered. “I’m a trained hairdresser.”

All this was nearly amusing. An institution that started out with two female members, and then waited more than a hundred years before electing any more, had ridden valiantly into the gender wars and then quickly scarpered. The same academy that had had no difficulty welcoming the art of the bestial paedophile Eric Gill, who raped his daughters and shagged his dog, was moved to ban Jess de Wahls because she had expressed some views on social media with which not everyone agreed.

Last year the Tate was supposed to have mounted a retrospective of the fierce American naysayer Philip Guston, a lifelong anti-fascist whose work never missed an opportunity to take a pop at the far right. In his art Guston had sometimes made sarcastic use of the Ku Klux Klan costume to illustrate his fears. I was really looking forward to the exhibition. But suddenly the Tate announced that it wasn’t happening. The Ku Klux Klan imagery was deemed too open to misunderstanding.

The show’s dismayed curator went on Instagram to lament the decision. He was suspended from his job. Six months later he left the Tate entirely.

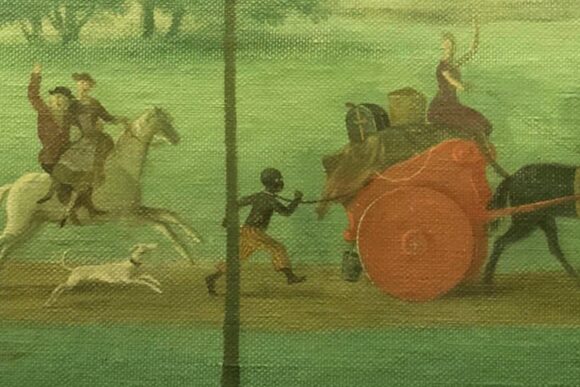

The Covid era shook the common sense and the courage out of our pampered museums, exposing the fragility of their beliefs. Look what happened with the Tate restaurant affair. The murals in Tate Britain’s downstairs restaurant, painted in the 1920s by Rex Whistler, are examples of a weak interwar decoration that no one usually bothers to look at. But two feisty internet bloggers who call themselves the White Pube bucked this trend and noticed that within Whistler’s jolly celebration of colonial romping were scenes of young black slaves being dragged through the fields by the chains around their necks.

Disgusting. Imagine a black family, eating at the restaurant, being forced to sit under this wicked and dehumanising imagery. Yet instead of covering up the torture scenes, or contextualising them heavily, the Tate just let it ride. With Guston, they cancelled courage. With Whistler, they cancelled decency.

So, yes, Covid has tested our museums and galleries as they have never previously been tested. And, yes, the results tipped mostly into failure. Did any of the leading museums emerge from the exam with gold stars on their report? Yes. One. The National Gallery. Which didn’t put a foot wrong during the entire endless torture of Covid.

Last to close, first to open, decently sized but not enormous, the National managed even to delight us with a couple of superior shows, notably the fabulous Artemisia Gentileschi exhibition. Another new initiative, sending works from the gallery on a tour of unlikely venues in Britain — schools, hospitals, prisons, libraries — has been a resounding success.

When lockdown eased, the National immediately found a way to let us visit again with some safe and carefully planned routes through the gallery. There are even those who insist that the calm, sparse, slower-paced National Gallery of the Covid era is the best they have wandered through. I know what they mean.