The Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone is well known for . . . this is where it gets tricky. What is Rondinone known for? He makes sculptures, he makes paintings, he works indoors, he works outdoors, he does installations, he does land art, makes videos, takes photographs. There aren’t many ways of producing art that Rondinone hasn’t tried.

Yet there is something that holds this madcap creativity together: a tone, a mood. I cannot think of one word that encapsulates it, but here are a few that point in the right direction: innocence, dreaminess, hope, naivety.

To celebrate the end of the lockdown, Sadie Coles has turned over both her London spaces to him — the one next to Carnaby Street and the one on Berkeley Square. The two displays share a long and listy title: A Sky, a Sea, Distant Mountains, Horses, Spring — not much encapsulation there, then! And because Rondinone is so damned varied, the split shows are strikingly different.

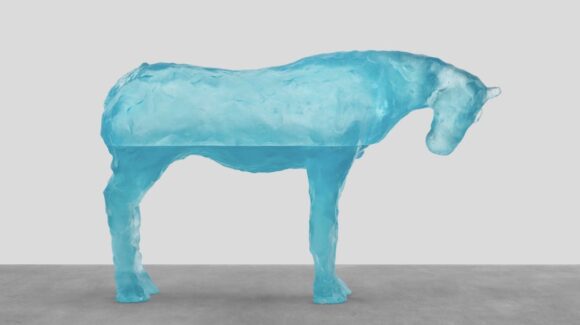

Carnaby Street is dominated by horses. You walk into a huge loft space and stretching before you is a concrete prairie on which stands a herd of 15 pint-sized ponies, made of glass, and coloured different shades of beautiful blue. Some are deeper blue, like a curaçao cocktail; others are frosty blue, like a Glacier Mint.

Because they are made of glass, the horses play with light, scattering it about in the manner of a glass carafe or a vase. Running through each of them, just above the legs, is a horizon line, created by a change in colour. And as you move through the room, it lines up magically with the walls behind. The clever detail brings with it an unexpected sense of gazing out at an empty sea. You’re indoors, but Rondinone has found a way to press the Ancient Mariner button.

The horses turn out to be the best thing in the two-part event. They remind you instantly of the celebrated German expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter (“the blue rider”) and especially Franz Marc, the recurrent painter of blue horses who was killed in the First World War. For Marc blue horses stood for a relationship to nature that had been lost in the modern world: an extinct spirituality. I suspect Rondinone has similar ambitions.

Over on Berkeley Square, the second part of the show has a different impact. This time you walk in to be confronted by a confusing suite of paintings that seem too big and too bright for what they are. Imagine a preschool teacher telling her kids to paint a Rothko. The kids oblige, but instinctively replace Rothko’s funereal mauves and blacks with cheery bands of felt tip. Their drawings are then enlarged and each patch of colour is given a shaped canvas of its own. The whole lot is then reassembled into a Stonehenge-sized mural that towers over you: giant deconstructed Rothko!

In a few of the shaped canvases Rondinone has left a handprint in the paint, or a footprint. They strike a palaeolithic note and prompt the immediate suspicion that we are being encouraged to remember the origins of art, and that the kiddie colours, too, are asking us to mourn something that has gone. Come to think of it, the blue horses had a prehistoric outline as well, as if they had jumped off the walls of the caves at Lascaux.

It’s a scattergun show, uneven in its successes. But all the way through you can sense Rondinone’s fierce yearning for a lost past.

Ugo Rondinone, Sadie Coles, London W1, until May 22