There’s a rustling in the burrow. Something stirs. Inside the burrow, art sticks out its little snout and sniffs the air. Sniff, sniff. After four months of hibernation it’s time to get out and about. Or is it?

I must say, I’m torn. Of course it’s wonderful that the museums are to reopen on July 4. It’s wonderful too that some private galleries are already letting you in (if you phone and make an appointment). Of course, after four months of staring at TV screens, we are all kick-down-the door, foam-at-the-mouth desperate to see some real art. But the lockdown was nothing if not a profound, one-off, life-changing experience, so before everything rushes back to how it was, there’s a moment to pause and ponder. And I reckon we should use it.

For me, the big takeaway from the lockdown is how much of what I imagined to be a crucial part of the art experience isn’t crucial at all. Indeed, much of what used to be filed in the “Crucial” drawer can now be confidently refiled in the drawer marked “Distraction”. The crucial stuff — the stuff that makes your heart pound, your eyes go dizzy, the tears well up, the anger rise — doesn’t need giant museums or mega-biennales, obscene auction prices or blockbuster events with intricate queuing arrangements. Those are the distractions. We might even file them under “Obstacles”.

Another thing I was not expecting to happen during the hibernation was for art’s importance to be magnified so often and so tangibly. For the whole of my career as an art critic I have had to bat away accusations that my subject was an indulgence: an elitist distraction. Now, suddenly, everyone was at it. Kids were making it. Parents were making it. Grannies were making it. People in hospitals were making it.

On the telly one of the biggest hits of the lockdown was the uplifting Grayson Perry programme Grayson’s Art Club, where he and his wife made homemade art in isolation and encouraged everyone else to do the same. It was such joyous, useful and happy television. I expected bakers to bake and sewers to sew, but alas — who knew there were all those itchy fingers out there desperate to make art?

The torrent of artistic endeavour that hit the internet was so huge I’m surprised it didn’t break it. Even Reese Witherspoon started painting watercolours on Instagram. With a brush. I started collecting those recreations of famous paintings that people began doing at home, and gave up when I got to 1,000. Anyone searching for evidence of the need to put art firmly back on the school curriculum, because everyone has an artist inside them frantically signalling to be let out, had that evidence dumped on their doorstep in huge piles.

And the lockdown hasn’t only emphasised our innate and instinctive need for art, it has also landed our professional artists in situations in which they found themselves working in unusually intimate and direct conditions. While making the Sunday Times podcasts I’ve been producing with the art historian Bendor Grosvenor, Waldy and Bendy’s Adventures in Art, I had the opportunity to interview some of the nation’s best-known artists — Perry, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst — and in every case they have talked of a new directness: an absence of distraction.

Emin was especially eloquent on the subject. Like everyone else she has stayed at home and worked, but unlike everyone else she revelled in the situation. You can see what she’s been up to in an online exhibition, mounted by White Cube gallery that is actually called I Thrive On Solitude. It features a selection of the small paintings she made at home in her living room. They’re whispery and delicate, intimate and ephemeral, filled with broken memories and powerful longings. Tracey remembering her mother. Tracey dreaming of a lover. Tracey in the bath. Going to Tate Modern isn’t an extension of this new Emin art. It’s the opposite of it.

The feeling I kept getting during lockdown was that the new circumstances were encouraging art to value the basics. Even Hirst, it, in fact, a sign that after decades of forming ever-wider rings around its core impulses — furiously colonising every art form it encountered, an artist notorious for the number of assistants he employs to make his huge artworks, found himself alone in the studio, with a paintbrush. He’s producing a series of 96 paintings of cherry blossom for a show at the Cartier Foundation in Paris. When I asked him if going back to painting can be understood as a significant choice, he quoted John Lennon at me. After he cut off all his hair in the 1970s Lennon was asked why he had done it. “What else am I gonna do after I’ve grown it?” he replied. Long hair, short hair. It’s the law of the pendulum.

Yet is that all it is? Or is from film to sound, from theatre to architecture — art had now finally reached the outer limits of this colonial expansion and was heading back to shore?

Even before the lockdown there was evidence that the intercontinental distraction was finally being reined in, and a more focused artistic spirit was abroad. I noticed it in particular in the work of a powerful generation of black artists, whose emergence in recent years has injected a shot of much-needed adrenaline into the dull veins of art.

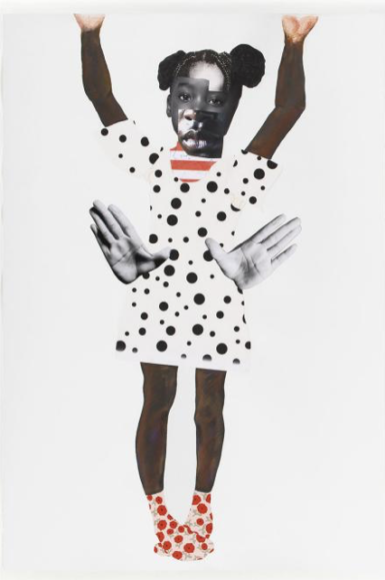

Artists such as Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Kerry James Marshall, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Deborah Roberts and Zanele Muholi are making art about exemplary modern subjects — race, gender, family — but they are doing so in ways that feel connected to the basic art impulse. To go forward, they’ve gone back. To storytelling. To painting. To the power of the image.

All this was evident before the lockdown. Since the lockdown it’s become a huge, glaring truth. Black art matters because it has real things to say, because it isn’t in the business of faffing about or pretending to be something, because it wants to convey not confuse, because the impulses that drive it are the impulses that have always driven art, and always will.

So yes, inside the burrow something universal has stirred. And I must say: it excites the hell out of me. When the world gets real, art gets real.