This column has developed new ambitions. Last week I managed to slip into the Titian show at the National Gallery just before it was closed. This week I’m writing about Lucas Cranach, the inhumanly prolific German Renaissance painter whose art was briefly on display in the dreamy stately home of Compton Verney in Warwickshire.

I did at least see the Titian show. With Cranach, I got as far as the kerb where my car was parked before my journey was redacted. Reader, you are witnessing the birth of a new literary genre: the concise conceptual appreciation.

Cranach (1472-1553) was a distinctive painter. You can always spot him in the galleries: heavily outlined nudes; the biggest, funniest hats in art; a unique Germanic tone that vibrates between serious and comic. He is also notoriously abundant. If you filled the Louvre with all the “Cranachs” in the world, there would be no room left for the Mona Lisa. His studio was huge and successful. He churned out art. And his son, Cranach the Younger, was nearly as good.

So it’s a snake pit. Even the picture I want to concentrate on here, The Fountain of Youth, in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, has a chequered attribution. Some say dad. Some say son. Whichever of them actually did it, it’s one of the most compelling images of the German Renaissance.

Societies from the ancient Greeks to the pre-Columbian Caribs have imagined a place where magic waters can reverse the passage of time. You go in old, you come out young. When this picture was painted, in 1546, the discovery of the new world was still fresh in European minds, and the fantasy still persisted that paradise had been found again and, with it, the possibility of eternal youth. Some of that is certainly going on here.

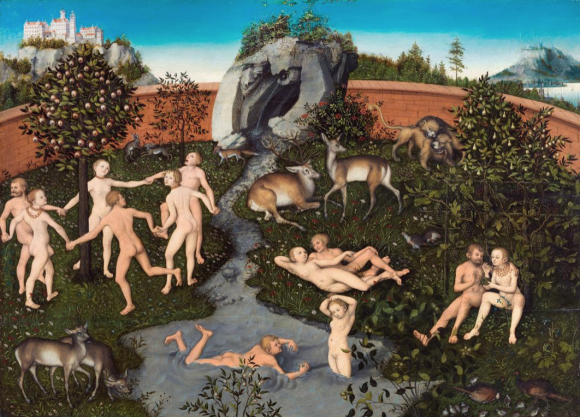

It’s a big picture for Cranach, 6ft by 4ft. In Berlin they have given it a wall to itself, so there’s a nice bit of theatre involved in approaching it, as if you too are heading for the bath. What we see is a rectangular pond packed with nudes — a northern Renaissance lido —set in an unlikely landscape. Weathered rocks on one side, fertile lowlands on the other. “Hmmm,” you think. “Symbolic.”

As you get closer, the chaotic nudes begin to separate into old women on the left — droopy, wrinkly, splodgy — and young girls on the right — wispy, pert, blonde. The old women are being carried in carts and wheelbarrows and stretchers by an army of old men. But only the women bathe. A figure in red, on the left, seems to be a doctor, who inspects them before they go in. On the right, the miraculously rejuvenated girls stepping out of the bath are being greeted by dashing cavaliers, dressed in typical Cranach party tights, who direct them to a tent where they can get dressed. And out they come, fashionable and gorgeous, ready to join in with the dances and feasts that have broken out on the merry side of the action.

The fountain of youth, meanwhile, from which the miraculous waters are spurting, is a decorated column at the end of the bath, topped with a statue of Venus and Cupid. Aha! The gods of love. The symbolic message here seems to be: love makes you young again.

So far, so dodgy. The men are coming out of this with a stream of youthful beauties to seduce, while the women are being put through an undignified aqueous update. It’s not a storyline that plays well in the modern world.

Cranach, though, isn’t really siding with the blokes. A deliberate note of ridicule is being struck: a sense that all of us — men, women, old, young — are just rowers on the Ship of Fools. Humanity. What a bunch of berks.

He’s not wrong, is he?

Cranach: Artist and Innovator is due to be at Compton Verney until June 14