There’s a joke that does the rounds in art-critic circles — well, more of a grumpy observation than a joke — about shows called Works on Paper. “When do you put on Works on Paper?” it goes. “When you run out of paintings and sculptures.”

Let me quickly expand that this grumpy boffola has nothing to do with real works on paper — with Dürer’s woodcuts or Raphael’s cartoons or Rembrandt’s etchings or the pastels of Degas. Those are most certainly things of wonder. However, there is a tendency in lesser artistic circles for dealers and galleries to mount events called Works on Paper when everything else from the studio has been cleaned out. They should call such events All That’s Left, but that isn’t dignified or tempting, so Works on Paper it is.

For those sorts of reasons, I was unaroused by the prospect of the Royal Academy’s new display, Picasso and Paper. There have been so many Picasso exhibitions, about so many aspects of his output, that Picasso and Paperappeared only to promise the barrel scrapings from the studio, the one thing that had not been done. Stupid me. From the first vista to the last, this turns out to be a show that plunges deep, deep, deep into the heart of his creativity. It couldn’t go any deeper.

Picasso and Paper isn’t really about Picasso and paper. It’s really about Picasso and the magic of his hands: the urge to make. Paper comes into it because it’s such a marvellously flexible resource that happened always to be around. In so many varied ways, paper offered him an extra-quick route from the idea to the product. The relentless magician could transform it into — well, anything, really.

That said, the opening view here plays safe by having a big painting in the middle of it — and what a painting it is. La Vie, from 1903, is the undisputed masterpiece of his blue period. It hangs usually in the Cleveland Museum of Art and has never been seen in Britain before. Cupboard-shaped, almost life-size, it shows a naked couple on the left, beckoning towards a bleak Madonna and child on the right. Everything is blueish. Everything is glum. Some huge truth about the dark meaning of life is obviously being ruminated upon by the jejune artistic imagination of a 22-year-old exile in Paris.

Plenty of others have investigated the specific symbolism of all this blue misery, so I have no intention of adding to their paperwork here. Suffice to say that the studies that surround La Vie make two things clear. First, that the man in the painting was originally a self-portrait. Second, that the scene is specifically set in the artist’s studio. It may be a glum rumination upon the meaning of life, but it is also a picture seeking to set an artistic agenda.

Where, then, is the paper, you may be thinking? Well, it’s all around. Sketches for La Vie. Moody drawings of melancholy Spanish faces. An unhappy self-portrait. A dreamy sex scene. His first etching, the exceptionally sad and fragile The Frugal Meal. And, beautifully and charmingly, a pair of cutout animals, a dove and a dog, made by little Pablo when he was eight. Wow. You want immediate proof of the talent in his fingers? There it is.

Having started with his juvenilia and his blue period, the show ahead takes a conventional route through the 70 or so years of furious creativity that follow. The blue period is succeeded by the rose period, when Picasso goes up into the Spanish mountains with his lover Fernande Olivier and turns her into a naked Venus in a headscarf, the pinks of her body done with clumps of local soil — Gosol’s red earth — mixed with water.

The rose period is followed by the pursuit of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Although the great painting itself can’t be here — MoMA would never lend it — a cluster of preparatory drawings leads us through the compositional try-outs that went into its creation. These drawings make obvious it was originally a brothel scene with visiting men in it. But by taking the men out, by enlarging the demoiselles and pointing them straight at us, Picasso is now casting us as the clients.

All this is fascinating. But it is also the standard use of paper as a surface on which to test out compositions and ideas. That stops being true in the next room, the one dealing with the invention of cubism, where Picasso and Paper soars onto a different artistic plane. With the arrival of cubism, paper stops being a surface to draw on and starts being a revolutionary substance with which to test reality and play with it.

Old bits of newspaper become Harlequins. Coarse bits of card become violins. Trashy bits of wallpaper become complex cubist spaces. The front page of La Semaine Economique becomes a cheap bottle of wine on a cheap cafe table. The lowly nature of the materials involved in these playful transformations seems in itself a spur. God made Adam out of clay; Picasso makes cubist masterworks out of discarded cigarette packets. It’s as if the alchemy involved in turning old bits of card into a cubist violin takes us to the bedrock of his magic.

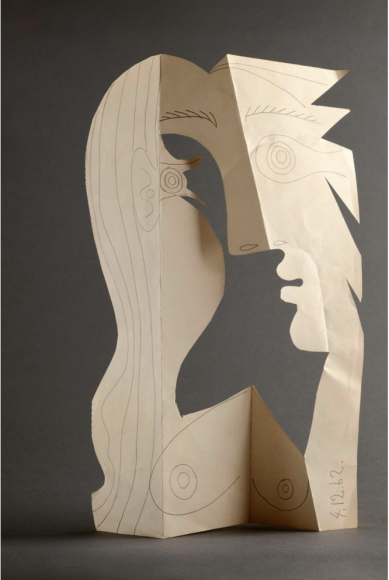

As I said, the show follows the conventional route through his career, so the divisions ahead are the divisions we’d expect. Nothing in the journey challenges Dora Maar’s famous observation that every time Picasso changed women, he changed styles. The Fernande era of cubism is followed by the Olga era of neoclassicism, where statuesque figures sporting statuesque expressions adopt statuesque poses in statuesque silence. Next it’s the epoch of Marie-Thérèse Walter, whose extraordinary face is transformed in a suite of brilliant simplifications — first in pencil, then in pen, then lithograph, then etching — into a cluster of interlocking sausage shapes that culminate, superbly, in a looming bronze sculpture of her head.

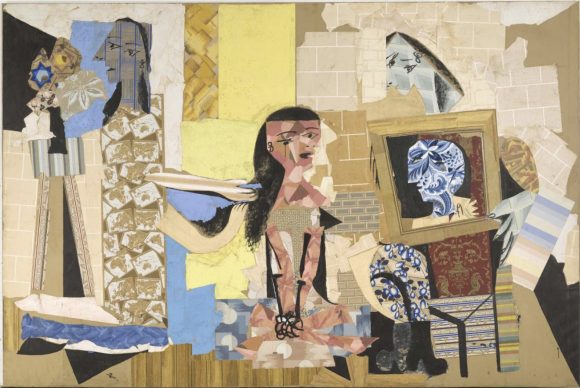

In all these moments, rich helpings of paper evidence (prints, drawings, sketchbooks, cutouts) are mixed with just enough pauses (key paintings, emblematic sculptures) to slow down the sense of constant, nay frenzied, experimentation. In Maar’s own era, the era of The Weeping Woman, her screaming sadness is immortalised in 1937 in one of his greatest etchings, and then, a year later, in the show’s biggest exhibit: a mega-sized collage of assorted wallpapers in which the weeping Maar stares at herself in a mirror, and sees him. It’s a weird and uncomfortable image, way down on the list of Picasso achievements, but the way the fragments of wallpaper create both an air of domesticity and a sense of fracture is wildly inventive.

As if all these lurches were not enough, the central gallery on the journey has been turned into a crowded market hall hellbent on highlighting the myriad ways in which Picasso worked with paper. He burnt holes into menus and tablecloths, made photograms and photo-scratchings, defaced pages of Vogue, printed in every manner of printing, scrawled on books and packaging, cut things out, pasted things in and even used the underside of a salad bowl to produce a woodcut.

A film of him at work, The Mystery of Picasso, shot in 1956 by Henri-Georges Clouzot, gets a room to itself near the end. It shows him racing against the clock to finish drawing after drawing while Clouzot, puffing at his pipe, counts down the seconds on every roll of film. Chess has speed chess; Picasso had speed art. He even has his shirt off for the effort. But the film’s most interesting revelation is how fearlessly he changes direction. First he draws a chicken. Then he draws eyes on it. Then he turns the chicken into a face. If you’ve ever wondered exactly what he meant by his celebrated comment that “every act of creation begins with an act of destruction”, this is it. Paper was precious because it was expendable.

Back in the central hall, the most surprising exhibit is a plaster cast of a crumpled heap of blank pages: Picasso’s homemade monument to paper’s excellent junkability. There’s an exhibition-long sense here that his reliance on it grows and grows. It culminates in the final exhibit, a self-portrait as a skull, drawn with crayons, that fixes us with a stare so fierce, it halts us in our tracks, like the buffers at a station. Thus this torrent of a show completes its journey with a palpable moment of stillness.

Picasso and Paper, Royal Academy, London W1, until April 13