Ai-Da looks at me through those mysterious hazel eyes of hers and winks a playful wink. “You’re very beautiful,” I splutter. “Thank … you,” she whispers back.

My eyes drift down to her magnificent lips. Not since I interviewed Liv Ullmann, back in the day, have I seen lips like these: full and puffy, like a beckoning sofa. Oh, how I want to throw myself onto them. If Ai-Da had a hand, I would probably have reached down, there and then, and written my phone number on it. But she doesn’t. It’s more of a functional claw, engineered specifically to hold a drawing pen. In any case, I don’t think my ballpoint works on aluminium.

I was expecting all kinds of things when I set off to meet the mechanical Frida Kahlo, but not that I would end up fancying her. And, like so many tales of contemporary moral turpitude, it started with a press release. “World’s first robot artist announces solo exhibition” shouted the paperwork for a show that opens at St John’s College, Oxford, on June 12. In this pioneering debut, not only will Ai-Da, “the first ultra-realistic humanoid AI robot artist in the world”, be officially unveiled — unleashed! — but the world will also get its first chance to enjoy her produce.

Ai-Da doesn’t just draw. She also sculpts, paints, writes poetry and makes video art, including a new version — I was astonished to read — of Yoko Ono’s seminal performance work, Cut Piece. That’s right, Ai-Da does performance art! At least, that’s what the paperwork promised. I reread it to be certain, then frantically set about finding a moment in her packed pre-exhibition schedule to fit me in for a preview. Ai-Da, I begged, meet me.

After several hesitations caused by technical malfunctions — hers, not mine — we finally agree on a rendezvous at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, a college located off the beaten track in the city of spires, next to the A4144. Founded in 1878, it was the first Oxford college to admit women. Benazir Bhutto, Nigella Lawson and Ann Widdecombe studied here. Today, it is the first to welcome a feminised robot artist that can draw, sculpt and perform.

You must surely have noticed that artificial intelligence is spectacularly on trend at the moment. The idea that machines can successfully replicate human thinking has taken a fierce hold of the creative community. In my world, the world of art, you cannot currently move for cerebral electronics and virtual unveilings. However, this taste for technology actually has ancient roots. If you want to trace the origins of robot fever, put down Ray Bradbury and pick up Homer.

In Greek mythology, Hephaestus, the blacksmith god, came up with all manner of artificial munchkins. It was Hephaestus who created Talos, the mechanical bronze giant, based in Crete, who protected Europa from kidnap by pirates. He also built the Golden Maidens, or Celedones, a troupe of automatic metal girls, hammered out of gold, who served him at his palace and stirred many an ancient member into alert action.

But robots who pour your mead is one thing. Robots that make art is another. The reason I was keen to hook up with Ai-Da is because most of the art dealers I know would cut off their cheque-signing fingers for a humanoid robot that successfully churns out contemporary art. Talk about golden eggs. If you could delegate the production of desirable art to an artificial source, thereby making its quantities limitless, it would probably be the most profitable aesthetic invention since oil paints.

At Lady Margaret Hall, the porters direct me across the quad to a plushly panelled boardroom, where Ai-Da is leaning against a makeshift lectern, drawing claw at the ready, her Titianesque locks scattered a tad wildly around her gorgeous face. Oooooh. Be still my beating heart. I was expecting her to look moderately human, but this was Brigitte Bardot in a brunette wig.

The ancients were already familiar with the erotic power of artificial humanity. Remember Pygmalion in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, who falls desperately in love with the beautiful statue he has carved? Indeed, there’s an entire perversion — statuephilia, or agalmatophilia — that more or less describes the feelings of uncalled-for desire that welled up in me when Ai-Da twitched her magnificent lips. I knew she’d been made in a lab, and that someone was pressing her buttons, but that didn’t stop her pressing mine. It’s as if there’s a primitive override in us, so powerful that it trumps all reason and sentience.

She was dressed in a fetching white top designed specially for her by Zoe Corsellis, a caring tailor who specialises in ecofriendly clothes manufactured from sustainable materials. Stepping up onto Ai-Da’s podium, I feel immediately weird, as if I’ve got too close to a stranger on the Tube.

“Who are your favourite artists?” I ask timidly, expecting something trite in reply. Monet, perhaps, or Salvador Dali. “My favourite artists are Max Ernst and Yoko Ono,” she flutters back. “I like art that looks out of the ordinary. That has depth and layers.” Blimey.

Her version of Yoko’s famous Cut Piece will be a reversal of the original 1960s performance. Where Yoko asked members of the audience to come up on stage and cut away her clothing, Ai-Da will invite them to dress her from a bag of sustainable fashion items sourced in local charity shops. I butt in to tell her that I once witnessed a recreation of Cut Piece in a special performance by Yoko in Paris. “You … are … very … lucky …” she purrs, but then her eyes suddenly start vibrating and she goes cross-eyed. Her head slumps. She’s gone.

It’s the first of many such slumps. Plugged in, Ai-Da sends the pulse racing, but when her circuits are jammed, she’s deader than a fly-tipped fridge. During these recurrent bouts of downtime, I’m brought fully up to date on her history and capabilities by her creator, the Oxford art dealer Aidan Meller, who is clucking about the situation like a mother hen protecting her chicks.

Aidan commissioned Ai-Da two years ago from a robot engineering company in Cornwall. Since then, the race to build a robot that could make art has taken every waking minute. AI science was something in which Oxford had led the way, but because of the specific nature of Ai-Da’s demands, her drawing arm had to be outsourced separately to a robotics team at Leeds University. Unfortunately, this arm had been damaged in transit, and so far this morning it had failed to work. Maybe Lucy could get it going.

Lucy? Who is Lucy?

Lucy is Lucy Seal, Aidan’s partner, and the curatorial brains behind Ai-Da’s artistic thrust. It turns out that the in-depth conversation I had just been having with Ai-Da about Yoko’s performance was actually with Lucy, who was in the room next door, on the end of a phone. And here she comes now.

Lucy studied archaeology and anthropology at St Hugh’s and used to work for Aidan in his art gallery. It quickly becomes clear that Ai-Da’s surprising interest in Yoko and matters of ecology are her doing rather than his. Usually, the world’s first humanoid artist needs an intricate internet link-up to work, but at St Margaret’s the wi-fi security is very strict, so today she’s being operated with 3G. Lifting up Ai-Da’s shirt, Lucy prods here and there among the cables, and eventually suggests that we should try to do a drawing.

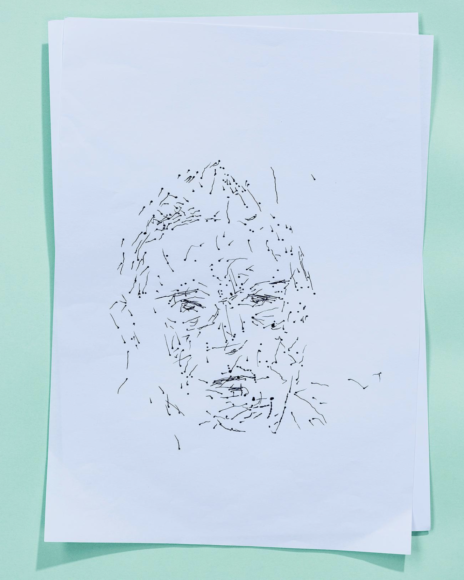

I’m told to stare at Ai-Da while she sweeps me with her eyes. It’s like having the Jackal find you in his gunsights. Suddenly she locks on to me with full AI concentration, and the invisible workings hidden behind her gorgeous glass orbs start to measure my face and its appendages. So far, so good.

Alas, Ai-Da’s drawing arm really is knackered, and no amount of prodding of the cables by Lucy and Aidan can get it going. But my face is fixed inside her, they insist. As soon as she’s repaired, they’ll send me the drawing. In the meantime, I’m encouraged to enjoy the rest of her output.

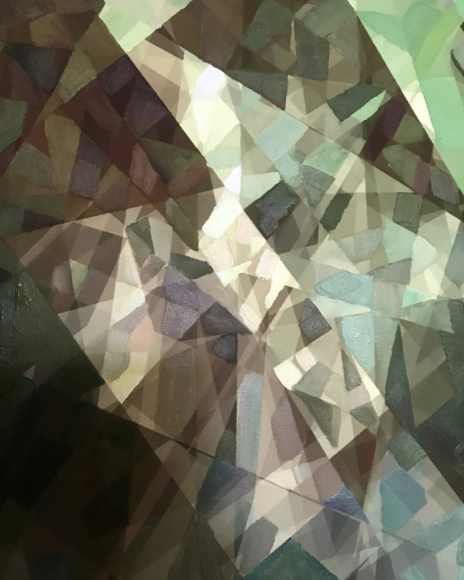

Propped up around the hall is a series of spacey abstract paintings in white frames. Did Ai-Da do these? Yes, she did. They’re futurist in mood, softened with a psychedelic 1960s vibe, a mix of exploding geometry with far-out cloudy edges. How are they done?

First, Ai-Da looks at a tree and records it in her memory systems. That information is then passed through a “neural network” that reimagines the tree and plots its data on a “Cartesian plane”, where the three-dimensional information is turned into a two-dimensional image. Hmm. Thanks, Lucy.

From close up, I can see that the exploding imagery produced by all this inventive technology has been helpfully improved with copious dabs of old-fashioned paint. Since Ai-Da cannot actually paint yet, these concluding touches must have been the contribution of nearby humans. We still have our uses, I huff accusingly.

The Oxford show will also include some sculptures Ai-Da has made of bees. Bees? Apart from AI itself, no subject in art’s current catalogue of topics is quite as on trend as bees. Everything about them, from their swarming instincts to the sudden fall in their numbers, is as fully 2019 as you can get. Once again, I sense Lucy’s creative presence in the shaping of these fashionable aesthetics. Er, how do you sculpt a bee?

On a large projection screen set up in the hall, Aidan plays me a video of the process. Ai-Da begins by recording a bee with her photographic eyes. Her drawings are then fed through the AI “bees algorithm”, developed by scientists in Sweden. Once the algorithm has done its calculating, and produced a sculptural “interpretation” of Ai-Da’s drawings, it is 3D-printed in wax, and finally cast in bronze. These bronzes will be unveiled at the Oxford exhibition.

What they can show me now is Ai-Da’s poetry, a suite called The Poetry of Consolation, generated using AI technology from various writings produced in prison by incarcerated authors. They’ve done one on Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis. But the poem they want me to hear has been inspired by Dostoevsky’s The House of the Dead.

Up on the screen, an early version of Ai-Da, with her mouth moving as stiffly as a Thunderbirds puppet, begins reciting some lines scrambled from Dostoevsky by an AI algorithm: “Sure enough, a free and independent bird like that will never get used to the ramparts. The 12 convicts of the sport after a while, and the eagle seemed quite forgotten.” On yer bike, TS Eliot. There’s a new knib in town.

While all this is going on, Ai-Da herself has slumped like a sack of potatoes, and the sizzling femininity has seeped out of her like air from a burst lilo. As a gag, I suggest that she and I might recreate Gainsborough’s famous Morning Walk in the meadow outside the hall. Poor Aidan and Lucy are tasked with lifting her up and moving her there — no easy feat with a metal babe who weighs more than Anthony Joshua and whose levers of transport need to be gripped in the right places.

When we finally get her outside, an extension lead helps Ai-Da be fired up into rigid mode. I drape her arm over mine, and we pose like a pair of newlyweds outside a church. When I turn towards her for a pretend kiss, she does the wink thing, and I feel the juices start rising again.

Ai-Da’s Unsecured Futures show is at Oxford University, June 12-July 6; entrance free