The Duveen Galleries, which run down the middle of Tate Britain, are the grandest rooms in the museum, and the most problematic. They were, after all, paid for by the wretched Lord Duveen, art dealer and crook, who made his money by flogging questionable Old Masters to gullible Americans, and whose many aesthetic crimes include “cleaning” the Elgin Marbles, in the British Museum, by removing their top surface with carborundum, the second hardest substance known then to science. Why? Because he thought they should look whiter than they did.

This vandal ought never to have been let near an art gallery, but instead our art galleries fell over themselves to take his cash and name grand rooms after him. Up in the heavens, however, the gods noticed this and were not amused, so they cursed the institutions taking Duveen’s lolly, and did so in cunning ways. At the British Museum, they made it impossible for anyone ever seriously to claim that the scarred and scrubbed-down Elgin Marbles left behind by Duveen’s “cleaners” in the 1930s were somehow safer in British hands. At Tate Britain, they made the huge Duveen Galleries, with their towering cliff-face walls, a spectacularly uncomfortable location for showing art. It’s like showing in a canyon. Nothing looks good in here. Or almost nothing.

I suppose another way of looking at it is to see the Duveen canyons as a serious artistic test. If you can survive in here, you can survive anywhere. Which makes the latest effort by Mike Nelson to conquer the cliff faces of Tate Britain the kind of effort for which they ought to hand out Victoria Crosses.

Nelson is no stranger to Tate Britain. In 2001, he was shortlisted here for the Turner prize, and should have won. The spooky labyrinth he created thrust visitors into a sinister underground complex through which you wandered, in the dark, and wondered, in the dark. Someone was spying on us from in here, but who? MI5? The CIA? KGB? Mossad? We never did find out. Nelson’s installations usually deliver the fun of the chase, but never the winning rosette.

A similar process keeps us guessing as we blunder through The Asset Strippers, a huge gallery takeover by heavy machinery that constitutes this year’s Tate Britain Commission, the annual aesthetic test of Britain’s artists that so often leads to failure. But not this time. Indeed, last year’s effort by Anthea Hamilton was an inventive pop at the problem as well, so perhaps things really are looking up at Tate Britain.

For The Asset Strippers, Nelson has filled the Duveen canyons with a bulky assortment of industrial equipment acquired, I read, from salvage yards and factory auctions. Back in the day, this is what made Britain great. Big green things for spinning cotton. Big blue things for stamping metal. Big black things for drilling holes. Big grey things for lifting the green, blue and black things.

I make no apologies for not having a clue what this heavyweight cast originally achieved. The point here, surely, is that they are no longer achieving it. Grubby, oily, faded, looming, the mysterious metal monsters were once the engines of the industrial revolution. Today, their only task is to take up lots of space in the Duveen graveyard, and to lie there looking broken and unwanted.

Plenty of nice touches enliven the installation. To get into the galleries from the different corners, you need to push through various sets of battered doors acquired from closing hospitals and failed housing estates. The Duveen Galleries are posh and pretentious. The old doors are kicked-in and humble. So there’s an immediate sense of slumming it, and a prediction, perhaps, of future failure.

By dividing the enormous spaces into separate “salvage yards”, each with its own selection of industrial junk, Nelson manages to inject a sense of journey into the visit. It’s nothing like as complex as his labyrinthine tunnel installations, but it brings punctuation to what would otherwise be a relentless parade of similar sights.

Best of all, some of the machines have powerful sculptural identities that turn them into genuinely effective ready-mades. The two red weighing contraptions looming up in the central rotunda, onto which Nelson has heaved some useless bits of broken concrete, have an unexpected pathos to them. Whatever it was they used to weigh, it was not hopeless bits of broken concrete.

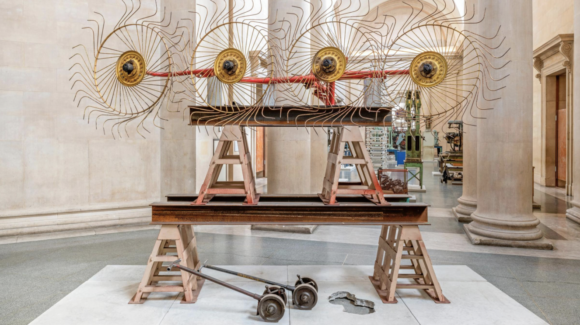

Also in the rotunda, a massive piece of tyre track, folded into coils, has a sinister mood to it more commonly found in lurking anacondas. And heaven only knows what the original purpose was of the violent set of spiked wheels lifted up onto a pedestal. The instinctive guess made by my stomach was that they sliced up something soft and vulnerable.

This is what sculpture can do that no other art form can match: communicate with you inchoately, on a body-to-body basis. That said, the Duveen Galleries are unfeasibly huge and some stretches of the show feel repetitive. As a lifelong aficionado of the junkyard, Nelson no doubt sees things in the thrusting levers and oily slabs that we virgins of the Spinning Jenny are likely to miss. A fair number of his mechanical monsters fail to achieve a sculptural buzz. But The Asset Strippers, as an entity, scores three big wins.

First, it dings and dongs an insistent lament on the passing of a great manufacturing age, and accuses the present of nothingness and insubstantiality. Second, it fights the corner for a sculptural tradition that relies on heft and weight for its messages, rather than conceptual delicacy and elegant visual conceits. Third, it smears oily fingerprints all over the portentous neoclassical walls of the Duveen Galleries, and smearing oily fingerprints on the Duveen Galleries is like stepping on a cat’s tail: everything springs to life.

At the White Cube gallery, the brilliant video artist Christian Marclay is doing what he always does: impressing us with his diligence, his inhuman work ethic and his geeky fascination with the minutiae of film making.

For his masterpiece, The Clock, which is still doing the rounds of the world’s art galleries, he scoured a zillion movies looking for references to time until he had enough split-second moments to assemble a fully functioning 24-hour clock.

In his new show, he turns instead to the subtitles at the base of a film — the forgotten lower reaches — and from these tiny slivers of partial information constructs a hefty new narrative that unfolds from hope to love to tragedy at the frantic pace of a jackpot payout on a one-arm bandit. Bang, bang, bang.

In landscape painting, there’s a genre called the sous-bois — “under the trees” in French — in which the artist focuses on something modest on the forest floor and, by focusing on it, rescues it from anonymity. Something similar happens here. Out of narrow slivers of images and words, constantly changing in tone and colour, Marclay creates a concrete poem that can be read from top to bottom, or from bottom to top, or both ways from the middle.

A thousand haikus have been transformed into The Odyssey.

Mike Nelson: The Asset Strippers, Tate Britain, London SW1, until October 6; Christian Marclay, White Cube Mason’s Yard, London SW1, until May 15