For proof of how firmly we are now embedded in an age of unreason, it is no longer necessary to watch the meeting between Kanye West and Donald Trump, or to follow the career trajectory of Danny Dyer. For clearer, simpler, funnier evidence, it is enough, these days, to walk into an art gallery.

To witness how bonkers some corners of the art world have grown, I heartily recommend a visit to the Serpentine Gallery, in London, followed by a trip to the Camden Arts Centre. At the Serpentine, I stared as deeply as I could muster into the pale “radiesthesic” scribbles of Emma Kunz, while the suspicion mounted in me that L Ron Hubbard had somehow managed to curate this show from an extraterrestrial throne in another thetan age.

Don’t worry. He hadn’t. Who needs scientology when you have Hans Ulrich Obrist, the Swiss super-curator whose reign at the Serpentine has reached some sort of art-critical nadir with this ridiculous, demented and outstandingly silly tribute to a fellow Swiss crackpot?

Kunz (1892-1963) is described here as a “visionary artist, healer and researcher into nature”. As a child in rural Switzerland, she discovered she had “extra-sensory powers”, including telepathy and prophecy, and at 18 began “to use her gifts” to heal people and predict their futures. In her forties, with the help of a “divining pendulum”, she started making the laborious geometric drawings on show at the Serpentine.

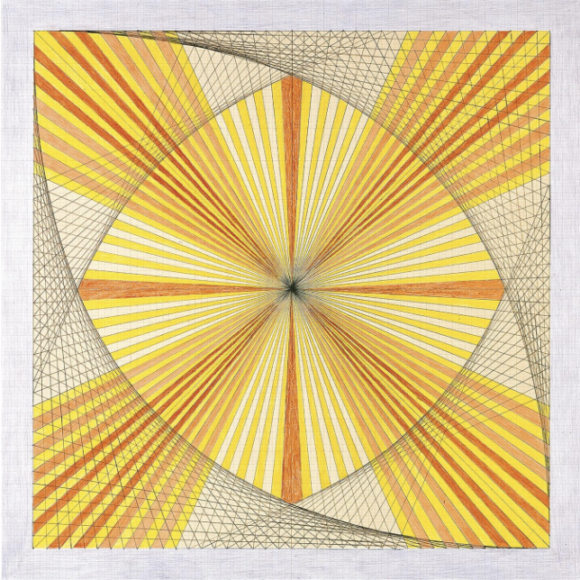

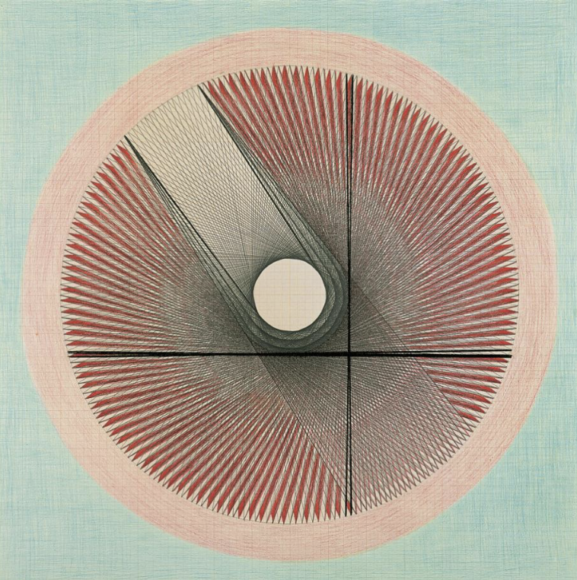

I’m not sure how Kunz’s “divining pendulum” actually worked, but it appears to have responded to the secret palpitations of her body, and the drawings she made under its guidance apparently record the “swings, stops and starts” of her divined aura. Think Spirograph, but bigger, with precise multicoloured lines of crayon and pencil crisscrossing large sheets of graph paper, producing a pale op art that pulses and throbs, but only mildly: a psychedelic Bridget Riley, except more timid.

Kunz apparently used her pendulum-driven art in healing sessions “in which she would lay the drawings on the table between herself and a patient in order to divine energy disruptions”. Never shown in her lifetime, the 400 or so “radiesthesic” drawings she produced are preserved in a shrinal centre called the Emma Kunz Zentrum, in Würenlos, where they also sell extracts from a holy rock she discovered nearby, called AION A. This, too, is on sale in powdered form at the Serpentine, at £35 a pop.

AION A, which Kunz stumbled across in 1942 in a quarry abandoned by the Romans, has, I read, powerful healing properties. It cures rheumatism, light burns, insect bites and itching. Kunz would sit in a grotto filled with it “to recharge her batteries”, so the Cypriot sculptor Christodoulos Panayiotou has been commissioned to make benches out of the rock, and these have been placed in front of the drawings.

The idea is that you sit on the benches, soaking up their healing vibrations in deepening communion with Kunz’s doodles. I tried it. Nothing. The drawings are quite pretty. And Kunz is not the first loopy artist to imagine that their work has profound interdimensional influence. But in the days of the Wild West, people in travelling medicine shows got shot for selling snake oil. Why is it OK to do it today?

At the Camden Arts Centre, the even loonier art of Grace Pailthorpe (1883-1971) and Reuben Mednikoff (1906-72), inventors of Psychorealism, has been unveiled in a tortuous retrospective that plunges off the scale on the unreason-o-meter. It is also a deeply creepy event and left me wishing I had a Thermos of AION A tea with me to stop the mounting nausea.

Pailthorpe was a doctor and psychoanalyst who served honourably in the First World War, then spent the rest of her career growing increasingly nutty. She met Mednikoff in 1935 at a party in London, when she was 52 and he was 29, and they became lovers. They went on to create a body of intense surrealist art that they christened Psychorealism, in which she played the role of a “surrogate mother haunted by the trauma of birth-giving” while he explored his “anal-sadistic tendencies and postnatal obsessions”. Yes, that old chestnut.

Mednikoff, who had studied at St Martin’s, in London, initially did most of the painting. Jewish and troubled, full of inchoate anger, he blamed his father for taking his mother away from him, and, according to the excited commentaries written by Pailthorpe, scrawled on the back of his frantic blobs and swirls, his art should be seen as an expression of desire for his mother, obstructed cruelly by the castrating penial presence of his father.

Pailthorpe also instructs us to understand his radiating blobs and multicoloured smears, his hairy protrusions and one-eyed monsters, as a child’s gift to his mother that the cruel father has forbidden. The act of painting she interprets as an adult expression of the infant’s need to play with its own faeces.

Now, psychoanalysis certainly has its role to play in art interpretation and, in the 1930s and 1940s, prompted some genuinely exciting developments in art: not just in surrealism, but in the abstract expressionism of Pollock and Rothko. However, the results of its influence we see here feel as if they have had all the poetry and grace forcibly removed with pliers.

Anuses turn into vaginas. Hairy protrusions plunge into flabby openings. Some carefully painted breasts are attacked by an enthusiastic little munchkin that ejaculates balls of white sperm on them. Filled with anger, spitefulness and uncensored lust, these horrible little pictures have abandoned all charm, all elegance, all adventure, as they stick grimly to the task of probing about inside the shrivelled emotional lives of Mednikoff and Pailthorpe.

After a couple of wallfuls of this relentless psycho-chundering, I found myself yearning for the relative calm and airiness of Kunz’s visionary radiesthesia. That’s how bad it got.

Emma Kunz, Serpentine Gallery, London W2, until May 19; Grace Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff, Camden Arts Centre, London NW3, until June 23