There’s a narrow acre of posh West End, just south of Piccadilly, just north of Pall Mall, which they call “Clubland”. It’s called that because for 200 years this was where the gentlemen of land had their smoking dens and their discreet eateries. Today, many of the gentlemen’s clubs have gone, but the money’s still there. It used to be cotton money, shipping money, slave money. Now it’s mostly art money.

Clubland, or St James’s as the estate agents prefer it, is a luxury London zone packed with art galleries and Tudor-style shopping opportunities. When you walk down Duke Street — past the Bernard Jacobson Gallery where they sell Matisses, past Moretti Fine Art where they sell Guercinos, past the Rafael Valls gallery where you get your Romneys — you are walking down the densest concentration of top-of-the-range art collectibles in Britain; perhaps in the world. And then, when you turn right onto King Street, you get to the headquarters of Christie’s, the auctioneers. And that’s where the Monopoly money with which Clubland is soaked drips and pools into the highest concentrations.

Christie’s has been in King Street for nearly 200 years. And the reason it has survived that long is because it keeps adapting. You don’t get to be one of the two most powerful salerooms in the world (hello, Sotheby’s!), which between them are responsible for 80% of the global valuables that fetch $1m or more at auction, by loving art and wanting to admire it. You get to be Christie’s by twisting and slithering, darting here, darting there, shedding the old skin, growing a new one, like a well-oiled grass snake.

Which is why, on Thursday evening, a procession of black limousines will start dropping off clients on the plush steps of No 8 King Street, and why, from Hong Kong to Los Angeles, the internet will start throbbing as anxious forefingers itch to press the “bid” button. On Thursday, the George Michael Collection comes up for sale in Clubland. And a battle royal will commence for the problematic goodies with which Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou chose to surround himself.

Celebrity auctions are a relatively new thing. It wasn’t until the 1970s that auctioneers began to notice how attaching a famous name to a slip of useless material stopped it being useless and started making it expensive. Judy Garland’s battered red slippers from The Wizard of Oz, sold by MGM in a golden age of Hollywood auctions to pay off the company debts, are historically credited with starting the trend. The slippers went for $15,000. And the celebrity auction was born.

In those days, contemporary art was the weakest chick in the auction nest. Put up a sign saying Contemporary Art for Sale and queues would form in the opposite direction. But the great virtue of contemporary art is that it is a bottomless pit, filled with inexhaustible supplies of golden eggs, so the big auction houses cunningly set about turning it into a desirable auction commodity. By the mid-1990s the transformation was complete. And an even brighter solution loomed out of the money fog. Why not combine the celebrity auction with the sale of contemporary art and engineer a double whammy?

In 2016, David Bowie’s collection of British modern art, offered by Sotheby’s in two parts, fetched a staggering £33m, and sent the auctioneers scrambling for follow-ups. So desperate were buyers to nab a Bowie relic that some of the pieces in the sale shot to 10 times their auction estimate.

Nothing on that scale will happen this week. The George Michael Collection is a different and smaller body of work. But the auction category it occupies is comparable, and the fan worship it will trigger is sure to lead to some eye-watering results.

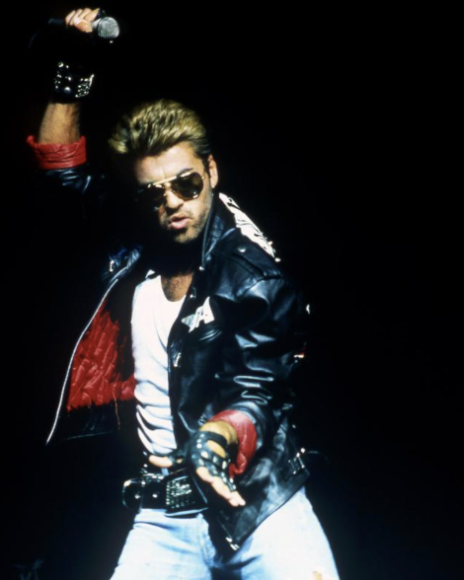

Only a few people knew that Michael was an extravagant art collector. It was, like his exceptionally generous charity work, a predominantly private practice. With most aspects of his careless life, there were careless whispers. But not about his art collecting. His taste for contemporary art, and especially for the so-called YBAs, the young British artists who rose in the 1990s and fell in the 2000s, was an amour fou, but, unlike his other madnesses, it never became a public spectacle.

At the height of the spree, between 2006 and 2009, Michael was probably the most active art collector in the world. The Christie’s sell-off will feature about 200 works, divided into a smaller sale of more modest pieces — internet-only in the latest art fashion — and a bigger evening event for the longer money battles. It’s a large bite out of the collection, but certainly not all of it. No one can tell me exactly how many things Michael bought in his splurge, but they all agree that money was flowing out of his suitcase like water over Niagara Falls.

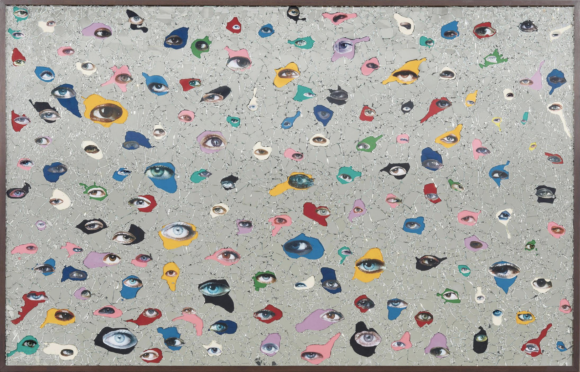

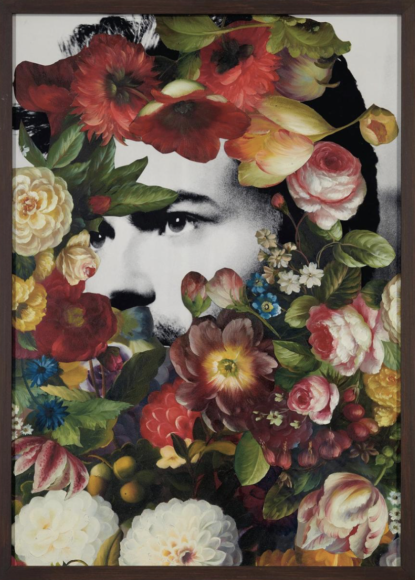

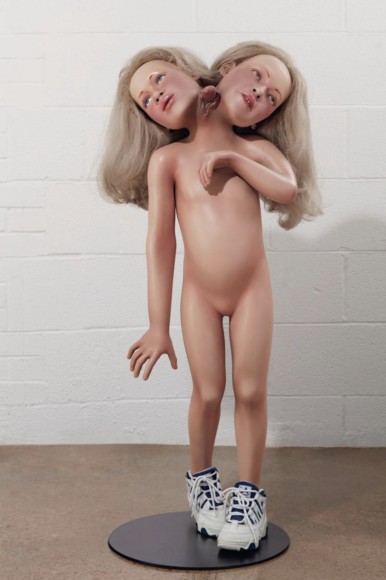

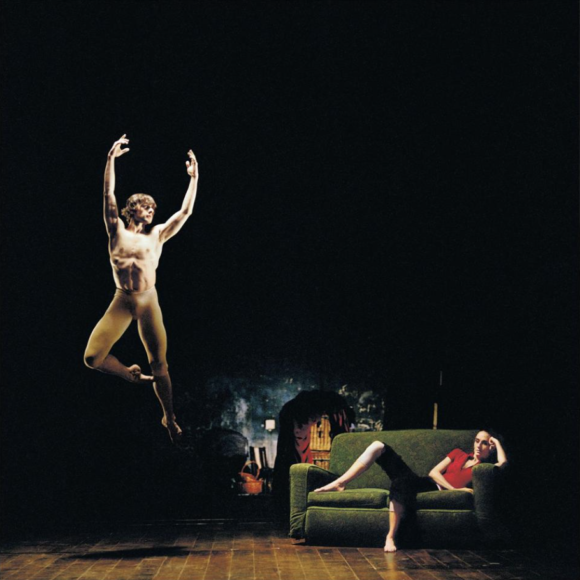

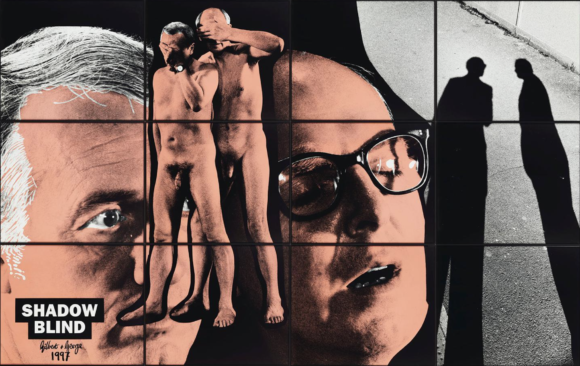

In the sale will be a stack of Damien Hirsts and a wallful of Tracey Emins. There will be Antony Gormleys and Marc Quinns, Sarah Lucases and Sam Taylor-Johnsons, a photo piece by Gilbert & George and one of those perverse intersexual naked munchkins created at the height of Sensation fever by the Chapman Brothers: half adolescent boy, half adolescent girl, double sexed, doubly problematic, a Siamese cocktail of genital confusion with ambitions to mock the genetically modified world in which we live.

Not many people would invite the Chapmans’ two-headed sex monster into the house. But George Michael wasn’t many people. He knew all about sexual confusion and, like so much of the art in his collection, Platinum Joey (estimated price £15,000-£20,000), as the munchkin is called, would have hit a private nerve. Besides, he had a lot of houses.

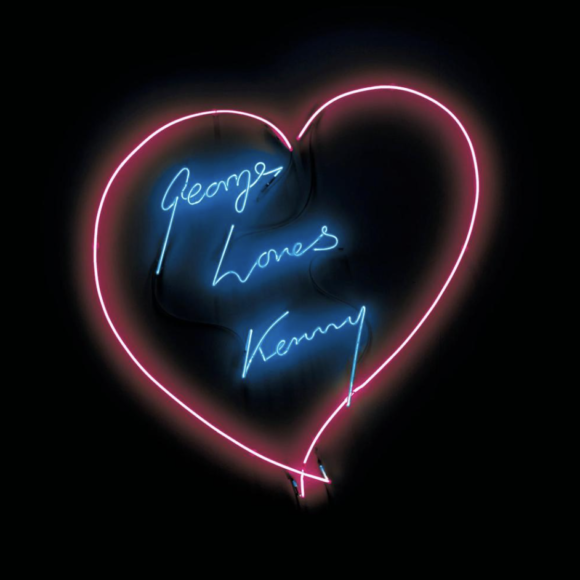

The personal nature of the collection is a notable feature of it, and a rare one. Among the selection of Emins is a neon piece titled George Loves Kenny (£40,000-£60,000), in which the Mouth of Margate has scrawled a Valentine message in lovesick blue across a glowing pink heart. You and I get to carve the name of the one we love on the bark of an oak tree in the local rec. Michael commissioned Tracey Emin to say it for him in film-star neon.

Emin was Michael’s closest friend among the raggle-taggle YBAs whose art he collected so furiously. She’s the one who introduced him to all her YBA pals and engineered the intimate communion between Michael and his art that makes this a special selection. I tried to get her to speak to me about it, but she shot back across the ether with a refusal. “I’m sad about the sale and sad that George isn’t around” is what she texted.

Tim Noble, the preternaturally youthful and spiky half of the art duo Noble & Webster — who have five lots in the big half of the sale — foggily remembers the parties, the concerts and the late-night home visits that came with being a George Michael artist. Emin introduced them. She introduced everybody. Occasionally, after a gig, Michael would invite Noble to his house in Highgate, where you never knew who would open the door. Once, it was Ginger Spice.

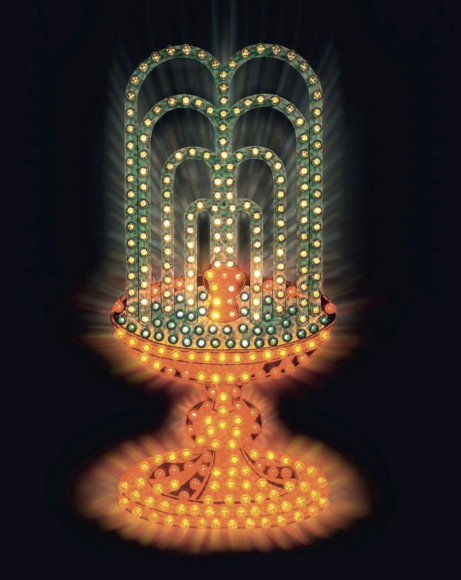

Every one of the Noble & Websters in the sale is a cracker. Excessive Sensual Indulgence (£30,000-£50,000) is another glowing neon in which a fountain erupts happily into none-too-subtle cascades of spouting water. In Metal F****** Rats (£15,000-£20,000), one of Noble & Webster’s signature shadow pieces, a bright light shining on a pile of twisted metal on the floor throws a miraculous shadow on the wall of two happy rodents going at it like Whammed-up rabbits.

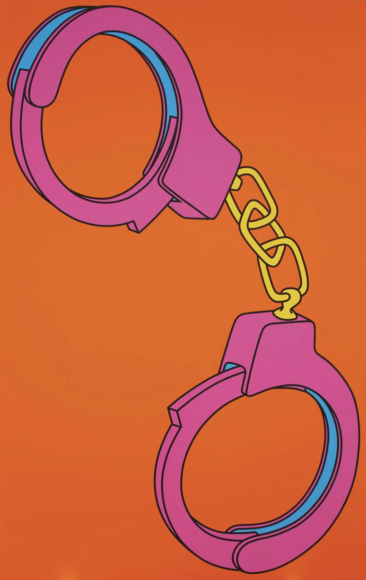

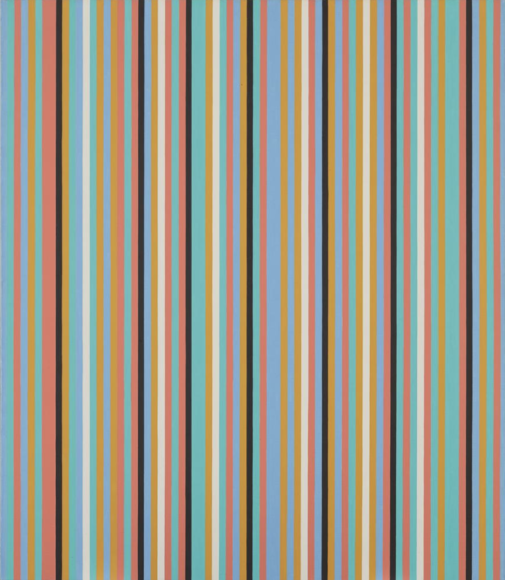

Sex is a recurrent theme. The first works sold to the singer by Michael Craig-Martin, the Goldsmiths teacher and guru who is invariably cited as the inspirational tutor of the YBAs, were two trademark Day-Glo acrylics, one featuring a urinal, the other a pair of handcuffs. The Wham! star happily confessed they reminded him of his notorious arrest in a Los Angeles public lavatory in 1998, which forced him to come out as gay. You may remember the headline it prompted in The Sun: “Zip me up before you go go”. Craig-Martin’s small urinal is estimated at £18,000-£25,000. The big handcuffs at £30,000-£50,000. Put all these together and you have an overall sale forecast of £6m-£9m. Not in the Bowie league, but a serious spend nevertheless.

All the artists I talk to have only kind things to say about Michael. In his art dealings, as in most aspects of his rollercoaster life, he was shy, intelligent and sweet. “A very private person,” confirms Marc Quinn, the notoriously brainy YBA who has a couple of works at Christie’s and who created that giant statue of the paraplegic Alison Lapper that stood so poignantly on the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square in 2005. “I’d go round to the house sometimes. By this point, he didn’t go out much. I think earlier in his career he did. But by this point he was quite a recluse.”

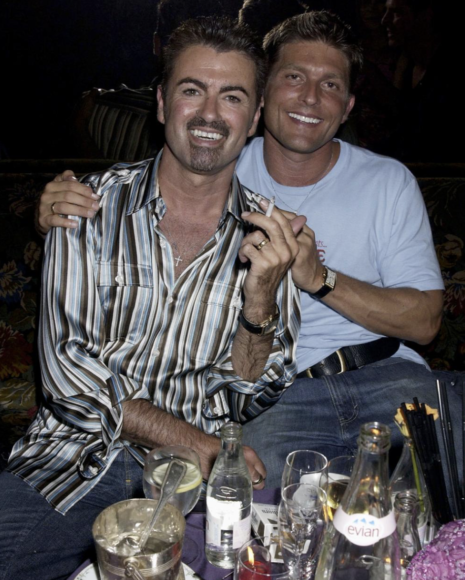

Something else that keeps coming up in the reminiscences is the role played in the making of the collection by Kenny Goss, the long-standing boyfriend loved in neon by Tracey Emin. Goss, everybody agrees, was the driving force behind Michael’s collecting. As one lucky dealer crisply put it to me: “Kenny had the enthusiasm, George had the money.”

Goss was from Texas. He and Michael were together from 1996 to 2009. Thirteen years of soppy love, 15 if you count the attempted reconciliations. Before he met Michael, Goss had been an art dealer in Dallas. So it was his experience and know-how that led them both to the excitement and spunkiness of YBA art.

“He’s very sweet, very charming,” trills Sam Taylor-Johnson on the phone from LA, sending her love to Kenny Goss. “You know those confident Texans with big hats and good manners? Kenny is like that.” These days, Taylor-Johnson is a famous film director (she directed the first instalment of Fifty Shades of Grey) as well as one of the original YBAs whose work was added greedily to Michael’s collection.

Dallas, it turns out, is a big deal in the commercial art world, an important gallery hub around which spins a local jury of 12 fabulously rich collectors who have become magnets for international pedlars of contemporary art. The Goss-Michael Foundation, set up in 2007, is now a busy artistic centre that promotes and supports new work. Until now, it was also the home of the largest collection of impressive YBA produce outside Britain.

Marc Quinn is another who insists that the energy behind Michael’s art splurge was chiefly Goss’s. In fact, he’s about to fly off to Texas for a show at the Goss-Michael Foundation, where’s he’s also contributing to an annual charity auction, organised jointly with MTV, headlined this year by Rita Ora. Its task is to raise money for the treatment of HIV among the children of Africa.

Quinn is also represented heavily in the Michael holdings. “Once they decided they liked an artist, they collected them in depth. They did it with Damien. With Sarah Lucas. With lots of other YBA artists. And that’s the difference between a great collection and a stamp collection.”

The big sell-off at Christie’s will be raising money for yet more worthy causes. So it’s a very George Michael thing to do. But it is a shame, yes. “That’s the end of the collection,” agrees Quinn. “But then it had its moment. And sometimes collections have their moments. Then they get dissolved, and other people buy them. And they come together in different ways.

“I think it’s important to remember that the life of an artwork is always longer than the life of a collector or its creator.”

I told you he was brainy.

The public view of the George Michael Collection is open at Christie’s until Thursday, when the evening auction will take place. The online sale runs until Friday. Visit christies.com