When the ink finally dries on the list of the 20th century’s most significant photographers, I wonder how far up we will need to go to find the name of Diane Arbus? Somewhere near the top, I reckon. Perhaps at No 1. Because her significance seems to grow year on year. Time, an enemy of hers during her lifetime, has become increasingly helpful, you feel, since her suicide in 1971.

This suspicion of Arbus’s enlarging importance is given succour by a surprisingly warm selection of her early work that has arrived at the Hayward Gallery. Warm? Diane Arbus? The imagery for which she is so widely notorious, the disquieting portraits of dwarfs, strippers, gender-swappers, tattoo artists and other “freaks” — her word, not mine — is not imagery that generally prompts tenderness. And the format for which she is famous, the insistent square framing that gives her photography its evidential punch, was achieved with the twin-lens Rolleiflex camera she started using in 1962, nearer the end of her career than the beginning.

But when you step beyond these famous Arbus territories and encounter the pre-Rolleiflex artist, you find a raft of surprises. Shifts in focus. Change of mood. A body of work that contains the seeds of the Arbus to come, for sure, but that seems also to expand her emotional range and to make something gentler of her determination to search out difference. Where late Arbus, the notorious Arbus, feels as if it involves the pinning of her subjects to a board in order to inspect them closely, early Arbus is a freewheeling record of her adventures in New York and the curious folk she met on her travels.

All the images are drawn from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York, the chief repository of the Arbus archive. All are original prints, with that lived-in look that only time and oxygen can bestow upon an image. Although she began taking pictures in the early 1940s, with a camera given to her by her husband, Allan Arbus, she spent the first decade of her photographic career in a low-key watching mode. And it wasn’t until 1956 that she decisively captioned one of her negatives #1 and commenced the journey on which this show takes us.

In the Beginning, as it’s called, is a presentation of works made from 1956 to 1962, from the taking of negative #1 to the arrival of the Rolleiflex. Most of the pictures were shot with a 35mm Nikon and, even to a darkroom innocent like me, it is strikingly clear that many of the differences we are talking about here are camera differences. The Nikon works in rectangles, not in squares. Its images are grainier and less detailed than the Rolleiflex’s. And the way you use it, a quick lift to the eye, is a very different process from holding a Rolleiflex at waist height and staring down into its viewfinder. At its bluntest level, it’s the difference between noticing things and forcing them to happen.

Beautifully arranged on freestanding gallery columns that form a forest of images through which you wander and flit, the early Arbuses are chiefly about people. Of course. She was never going to have a secret past as a recorder of romantic landscapes or a hunter after geometric symmetries. And the people she encounters are already recognisable Arbus types.

A guy in a porkpie hat, snapped on a busy Coney Island beach, wears hefty shoes and socks with his swimming trunks, as if the beach is an extension of his daily grind, not an alternative to it. A young boy crossing the road stares quickly back at us with a surprised turn of the head, as if caught doing something naughty. A taxi has pulled up at some lights and its driver gazes absentmindedly out at us, through the window, as if he’s wondering why he is being photographed and has not yet decided if he likes it.

This narrative flux, the sense of an unfolding story, is different from the Arbuses to come. The characters are her kind of characters, but her photography has not yet pinned them down to a confrontational moment. Tilted up or tilted down, portrait or landscape, the Nikon rectangles are less fixed, more flexible, than the Rolleiflex squares. There’s more sense of movement to them. And a lighter touch to the confrontations they record between sitter and photographer, as if they have been happened upon, rather than forced through.

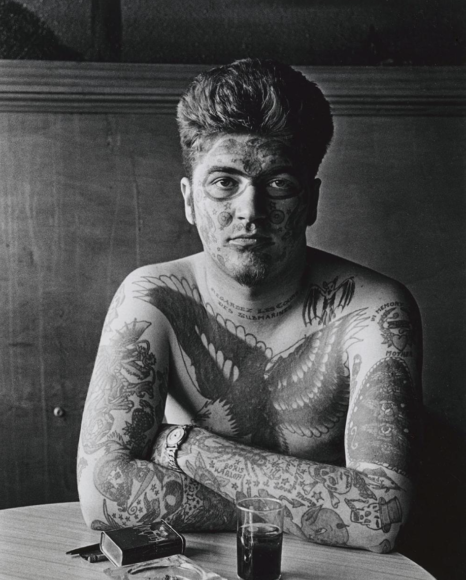

The America we are dealing with here is a different kind of America from today’s, as well: ill defined, more varied, more richly human. Arbus clearly had a taste for eccentrics, and there are plenty of big ones to be seen, but on the gentler side of that spectrum she notices people who are ordinary but characterful: interesting faces and curious expressions. To be photographed by early Arbus, you didn’t need to be covered from head to toe in bird tattoos, or to be born a woman and dress like a man. You just needed to look as if you had never been near a plastic surgeon, because what you are is all you can be.

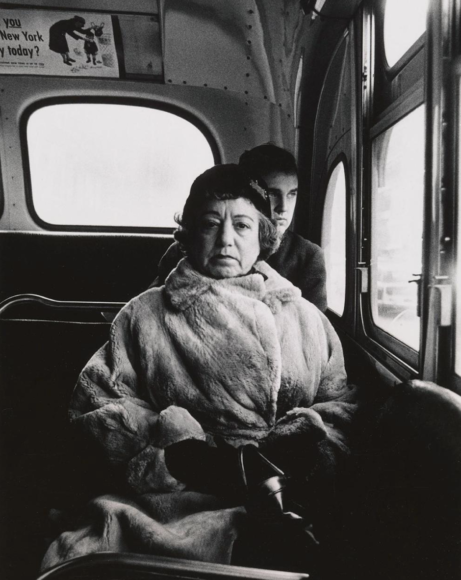

Caravaggio used to wander through markets and taverns looking for characterful faces because they brought a sense of insistent reality to his religious scenes. Something similar is going on in Arbus’s visits to Coney Island and the trawls she makes through New York’s Lower East Side. The people she finds — an angry woman on a bus; a couple having an argument on the boardwalk; a young black boy in an old man’s cap and jacket — are bit players shoved to the front, movie extras given a starring role, who snap the illusions of film-star America and replace them with something lower-case and tangible. It may not be as pretty as make-believe America, but you know you can trust it.

That said, if you are tattooed with birds from head to toe, or a man who was born a woman, then Arbus’s early photography places a big welcome mat in the doorway for you. Peer into the grainy and loosely focused rectangles of her Nikon years and you’ll find plenty of strippers, musclemen, circus contortionists and dancing queens looming glumly out of the silver-gelatin twilight.

Weighty books, several of them, have been written about Arbus’s wayward life tastes, the dangerous rides she took through New York’s underbelly, the shocking sexual encounters with dwarfs and swingers. She was certainly a woman on the edge, and it certainly prompted a furious empathy with others of that ilk. But one of the chief reasons why her art seems even now to be increasing in importance is because of its pioneering expansion of ideas of normality: its prescient acceptance of difference.

On the subjects of outcasts and deviations from the norm, our own era has pretty much come round to her way of thinking. The sad “female impersonator” from Long Island who pops up here in several poignant unveilings, smoking a cigarette, gazing into the mirror, floating between masculinity and femininity, is a study in social isolation: a fragile atom exiled to the outskirts of the molecule. He is just as ordinary as everyone else, but that ordinariness had not yet been recognised. In Arbus, different is the new normal, and I think Susan Sontag got it very wrong when she accused her of sensation-seeking and cruelty.

So there is much to savour in this early work — her empathy, her quickness, her generous world-view — and the technical implications are unexpectedly revealing. As I said, the show takes her career up to 1962, the year she started using her new camera, so we end here with a few famous examples of her final method. The Jewish giant is here, looming over his tiny parents. So is the grimacing boy in a park holding a hand grenade. And the identical twins, one happy, one miserable, whose divergent psyches ping and pong across the image like a rally on Centre Court.

It’s gripping photography. Harsh and brilliant. But when you know more about its origins, it too seems to enlarge and soften.

Diane Arbus: In the Beginning, Hayward Gallery, London SE1, until May 6