Picasso was not an admirer of Pierre Bonnard. Indeed, he loathed Bonnard’s paintings and dismissed them as “a potpourri of indecision”. This cheers me up, because it provides some serious artistic backing to the doubts that assail me whenever I see a lot of Bonnards. I go in with an open mind. I come out with blurry eyes. Too many marks. Too many colours. Too little sense of direction.

Tate disagrees, because it is once again heaping many Bonnards before us in shapeless clusters, having already done the same thing in 1998. Wait. I lie. The 1998 attempt was called Bonnard. This one is called Pierre Bonnard. And the earlier event included plenty of self-portraits. This one does not. Apart from that: same moods, same pictures, same problems.

Bonnard (1867-1947) was unfortunate in being born into the shadowy temporal trough that separates the post-impressionists from the cubists: an in-between time in French art, preceded and succeeded by great artistic moments. He wasn’t the only victim of these impalpable times. Right across Europe, it’s hard to find a definite contribution to the era. Even his most successful contemporaries — Toulouse-Lautrec, Klimt, Kandinsky, Matisse — seem defined by their variety. Only Munch among the giants of the epoch actually makes it feel like an epoch.

The Tate show tries to sidestep this imprecision by arriving late at Bonnard’s story. There’s no early work. No build-up. We encounter him when he is nearly 40 and happily settled on his final style. The rest of the journey, a dozen rooms of it, consists essentially of more of the same. Views of his garden. Views of his home. Views of his wife, Marthe, having a bath. Two world wars come and go, but you’d never know it as he dabs away contentedly at his retirement art.

Although the painter himself deserves most of the blame for this absence of development, the Tate curators have exaggerated his sameness by avoiding his beginnings. When we catch up with him at Tate Modern, he already has behind him a reasonably successful career as a poster designer, a Nabi and an intimiste. But there’s no sign of it.

Missing out on his Nabi phase is a particular lack. The Nabis were a flaky bunch of fin-de-siècle symbolists whose name was derived from the Hebrew word for prophet and whose work was influenced by Rosicrucianism, theosophy and the kabbalah. “Most of them wore beards, some were Jews and all were desperately earnest,” explained a wag at the time. By avoiding this phase, the show misses out not only on some much needed variety, but also on a modern understanding of his floaty perspectives and sci-fi colours, the radiating thought-forms and glowing auras. Instead, we get an immediate focus on his sex life and his intense relationship with his strange wife. So it’s very 2019: the Love Island Bonnard.

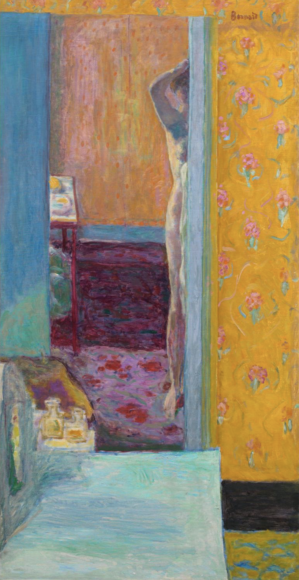

The opening pictures are smoky bedroom scenes featuring the painter in the Adam role and his naked wife, Marthe de Méligny, as an assortment of dappled Eves. Her face is usually a blur, but her body is recurrently picked out by the sun through handy gaps in the curtains. Sizzling with desire, these shadowy glimpses of Marthe are the best things in the show. Painted in subdued browns, pinks and greys, they reminded me of Sickert in his Camden Murders phase. It’s afternoon, but the curtains are drawn, and the dark shadows of lust have crept into the room.

Marthe’s real name was Maria Boursin — as in “Du pain, du vin, du Boursin”. She met him in Paris in 1893 and lied about her origins. He only found out the truth about her name and her background when they finally married in 1925. In between, she kept up a fiction that she was an orphan from a noble Italian line while he set about making her the fourth of his favourite subjects, after gardens, windows and rooms.

Marthe was a prize neurotic, obsessed with taking baths, a habit that resulted in scores of paintings of her stretched out in the suds, surrounded by bright mandalas of soapy colour. Bonnard’s records of his naked wife, usually in the bath, are an oeuvre within an oeuvre. The strange angles from which he looked down on her give the resulting pictures a symbolic shimmer, as if he was trying to impute some cosmic meaning to her endless bathing.

This bath pose is a straight steal from Byzantine images of the Dormition of the Virgin, and a more scholarly show might have searched here for some intentional references to the living death of a Mary. But this is not a scholarly show. It’s a parade of patchy late Bonnards, too many of which are interchangeable.

Having started out with some gloom, the show leaps into full colour once it buys into the myth that Bonnard was one of the great colourists. When it came to reaching for yellows and purples, he had no peers. But brightness is not the same thing as brilliance, and the evidence here points to a painter who was never entirely sure which blob to squeeze next out of the tube. So he squeezed them all, using a tiny brush to create big expanses of busy uncertainty.

How clumsily he outlines the decanter in the 1916 still life called The Checkered Tablecloth. And what is that shit-brown rectangle sitting on the same table, painted the year before? Is it a tray? A loaf of bread? As for his vegetation — it might be cheery, but it hardly ever bears an actual resemblance to an actual plant.

More serious still is the stiffness of his figures. When it comes to convincing anatomies, Bonnard makes Douanier Rousseau look like Michelangelo. The given wisdom on this is that he was more concerned with colour than with form, but so was Van Gogh, and his anatomies are never as comically awkward as Nude Bending Down, of 1923, or as clunky as Standing Nude, of 1928. In picture after picture, Bonnard’s endless dabs, reworkings and hesitations take him further away from the facts.

In an effort to give some shape to the shapeless journey that results, the curators have taken three conspicuous decisions. Two of them work. One makes everything worse.

First, they have included samples of his photography to reveal whence he copied his nudes and to explain the unusual cropping in his framings and the strange angles in his viewpoints. This is helpful. Second, they have included a run of paintings from which the frames have been removed, leaving only the unframed canvases. This works too. Bonnard painted on unstretched canvases pinned to the walls, and it’s not his fault that his work has subsequently been encased in such a high percentage of bad frames — some of the worst I have ever seen. Removing them is unquestionably an improvement.

The third curatorial intervention, however — showing his final pictures in a suite of rooms painted bright yellow — is a mistake. It’s bad enough seeing so much eggy yellow in the paintings without having to deal with it all over the walls as well.

So, how Bonnard managed to become such a popular painter continues to baffle me. Why the Tate should wish to celebrate him so ineffectually, again, baffles me some more.

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory, Tate Modern, London SE1, until May 6