I go both ways on Martin Creed. And on and off. And up and down. I’m in this spin because the first proper engagement I had with his work — at the Turner prize in 2001, which he won — left me loathing his output and everything it stood for.

You must remember Work No 227, as he called it, otherwise known as “The lights going on and off”. In an empty gallery at Tate Britain, the lights went on and off. That was it. That won the Turner prize. If you have seen as many shows as I have over the years, you will know that once every couple of weeks in studentland, some spotty wearer of conceptual L-plates will reinvent the “blank artwork”. (I know, I know, there won’t be any actual L-plates, but let’s move on here.) The blank artwork will invariably consist of a display area with nothing in it. You’re expecting some art on the walls. There is none. That’s the artwork. When Creed’s addition to this dreary catalogue of student predictability won the Turner prize, I was more than disappointed. I was angry. Had none of the judges that year ever seen a student show?

Anyway, I took against him, fiercely, and have spent the intervening years changing my mind, very, very slowly. Not about Work No 227. That was, and is, a waste of space. But about Creed himself, who has turned out to have an interesting brain.

For the London Olympics in 2012, you may remember, he got all the bells in the land, including Big Ben, to ring for three minutes at 8.12am. That was good. A few years ago, I was on a Turner-prize discussion with him on the telly when he performed one of his catchy songs while playing the guitar standing on one leg for five minutes. It was a hardcore effort, mightily impressive. You try it.

Predictably, the selection of new work on show at Hauser & Wirth is scatty and butterfly-light. There’s a ring of drawings with charming little word games going on in them. Some droll kinetic sculptures (a sock that goes up and down). Some strange sights (a piece of toast spread with gold). And these teasing visual haiku are enlivened and deepened by two unexpected “happenings”. First, a woman comes in and sings one of Creed’s songs. Then two blokes from the gallery appear with a trolley and remove two of his pictures, leaving the wall free for a 20-minute film. When the film has finished, the blokes with the trolley come back in and put up the pictures again.

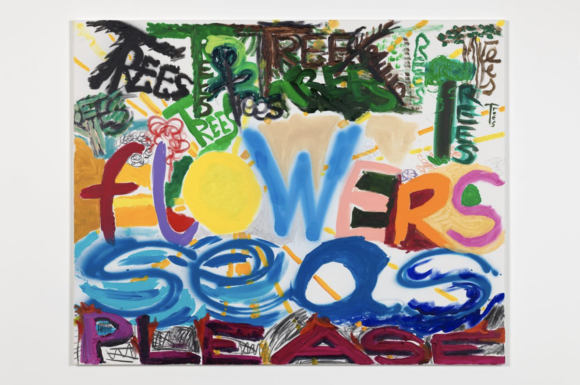

Creed’s paintings, though kiddie-coloured, are glum and nihilistic. Most are scattered with words that pop up in clusters to form a bleak accidental poetry. “Me”, “help”, “please”, says an anagram of hopeless thoughts heaped on top of a crap-brown hill. “Trees”, “flowers”, “seas”, says one of the paintings removed to show the film, adding, pathetically, “please”.

All this has a flavour to it. A Martin Creed flavour. He hasn’t got a distinct style. He hasn’t got a distinct look. But he does have a distinct flavour. The tragic sock going up and down, lifted and dropped unceasingly by an intricate piece of sock-lifting equipment, seems somehow to encapsulate one of the hopeless truths about existence. If Buster Keaton had made conceptual art, it would have looked something like this: bumbling but poignant, hopeless yet cheerful, gloriously pointless and smilingly bleak. It’s a beige sock as well: a particularly dull, loser’s beige, perfectly chosen.

There’s no tangible reason why a piece of toast spread with gold should look meaningful or loaded. But it does. It’s the old surrealist trick of the unexpected juxtaposition, flavoured with a sense of miraculous transformation. The humble piece of toast has gained a kingly presence. In human terms, it’s like a chap down the pub winning big on EuroMillions. So it’s all a bit Larkin-like: a loser’s poetry.

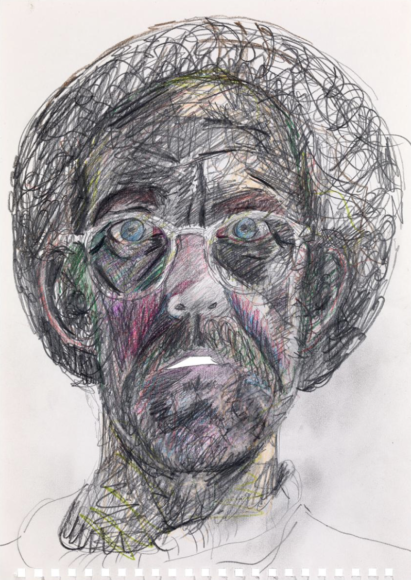

The film playing on the wall is edgier than any of this, and adds a note of psychosexual weirdness. It begins with a close-up of Creed’s nail-bitten finger poking itself into various surfaces, including his own shabby head. Having struck a fetishistic note, we move outdoors, where Creed, in white shirt and braces, progresses down a busy London street, clutching his head and bending double in a noiseless scream. Nobody bats an eyelid. We can all go completely potty, in full sight of the modern world, and no one lifts a finger.

The third bit of the film brings us face to face with a harem of silent women. The camera finds each of them very slowly. Then each of them opens her mouth, very slowly, to reveal what she has been chewing. Ambiguous white-stuffs, in the main. But also something orange and jam-like. And the gold paste from the toast. Thus the film triangulates between the seedy, the macho and the gem-like. As I said — a touch of Larkin. I was wrong about Creed. He’s a special presence.

That said, for a less fraught and more directly pleasurable experience, pop into the Bernard Jacobson Gallery, opposite Fortnum & Mason, where a show called Prints I Wish I Had Published confronts us with a wide selection of museum-quality imagery from Dürer to Warhol.

Jacobson has been running his gallery for 50 years. He started out publishing the great pop artists, then moved on to classic British painters before adding a smattering of abstract expressionists. So he’s a hardened old-school presence, and may well be the grumpiest art dealer in London when it comes to assessing contemporary art. But on the subject of the past, he has impeccable taste and a brave eye, and when he says he wishes he had published these prints, the true art lover is wise to scuttle along and check them out.

Dürer, Rembrandt, Goya, Gauguin, Munch, Picasso, Matisse, Warhol, Hamilton, Denny: they’re all here. Read the captions, written by Jacobson himself. They’re hilarious.

Martin Creed, Hauser & Wirth, London W1, until February 9; Prints I Wish I Had Published, Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London SW1, until February 9