There have been a lot of Warhol shows. And why he is so popular among the show makers is obvious. His brand recognition is huge. His popularity is guaranteed. He was spectacularly prolific, churning out enough art with enough changes of course to nourish a continuous torrent of displays.

But the most telling cause of his ubiquity is trickier to summarise. It’s to do with his preternatural modernity: that sense you get that he was always ahead of the game. He foresaw the era of celebrity. He foresaw the eradication of the divide between high and low art. He foresaw that one day people would machine-gun their grandmothers to gain a thimbleful of notoriety. He lived then, but he understood now.

At least, that’s what I used to think before I marathoned around the formidable Warhol retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York. It’s the largest Warhol show in history. It contains more than 350 exhibits in a dizzying array of media. It’s the first Warhol retrospective in the US for 30 years. And it’s a selection that takes a particular line through his achievements. To summarise immediately: it’s a pessimistic line.

The beginning is certainly desultory. Instead of a vestibule filled with gaudy Marilyns or strutting Elvises, we get a glum stack of Brillo boxes and a row of soup cans in a morose range of Campbell flavours: Beef Broth, Chicken with Rice, Cheddar Cheese. There was a time when those kinds of flavours in that kind of can might have struck a note of glamour, but not today. Today they feel like the unhealthiest options at the back of a corner shop that’s about to close.

A note of dankness is struck as well by the earliest painting in the show, a watercolour from 1948, done when Andy was 20, recording the family living room in Pittsburgh. Messy sofa. Cluttered settee. Brown walls. Brown carpets. The Warholas were working-class immigrants from Slovakia, and it shows. But what your eye keeps noticing is the insistent crucifix above the fireplace. It’s tiny, but it commands the space. Warhol died in 1987. Only then did we discover he had always been religious but had kept his Catholic life a secret. The tiny crucifix suggests as much from the off, and points the show in an unexpected direction.

Initially, his arrival in New York in 1949 feels like a release. Having trained as a commercial illustrator, he jumps happily into the world of advertising. A row of cheerful ladies’ shoes, drawn for the shoe manufacturer Israel Miller, capture the Cinderella moods of postwar Manhattan. You shall go to the ball, Mrs Vreeland. You shall wear lace and gold and crystals on your feet.

This sense of leaving behind a gloomy past continues in a row of homoerotic drawings of pretty boys and their sweet little penises. Sometimes they have bows tied around them — the penises, not the boys! Sometimes they are decorated in gold like homemade Christmas presents — the boys, not the penises!

All this is informative, but it seems also to be nursing a desire to make something bigger and more complex of his origins. Most Warhol shows get down swiftly to his signature pop art, the Marilyns and Muhammad Alis. Not this one. Instead, an etiolated beginning sees him experimenting messily with styles, methods and media. A big Superman cartoon from 1961, done with thick household blobs, has him brazenly pre-empting Roy Lichtenstein’s signature style. An early Coke bottle drips and runs as if painted by Jackson Pollock.

The unfamiliar hesitancy is exaggerated, perhaps, by the bitty nature of the opening displays. There are lots of drawings, not much colour; a taste for the black and white rather than the rainbow version. In an effort to give us a different Warhol from the one we’ve seen in all those other Warhol shows, this one is making him tougher to enjoy: not much sugar, lots of medicine. Even when he does emerge as a recognisable Andy, with a blown-up newspaper front page from 1962 that looms up in your path and blares out that 129 have died in a jet crash, it’s the melancholy Andy of the Electric Chairs and Race Riots you recognise, not the excited Andy of the Marlons and the Elvises.

The effort to present a more weighty artist is particularly telling in the middle sections: the most popular chunk of his career. It feels, in a word, curtailed. Heaven knows how many Marilyns and Elvises and Elizabeth Taylors he actually spewed out in the mass-production decades at the Factory, but for this revisionist event, the endless output has been reduced to a row of singles. One Elvis picture. One big Marilyn. One small Marilyn. Even Chairman Mao, the subject of so many Warhol variations, is only allowed a cameo. That said, it’s a spectacular one, taking up an entire wall and injecting high-octane wow factor into the centre of the journey.

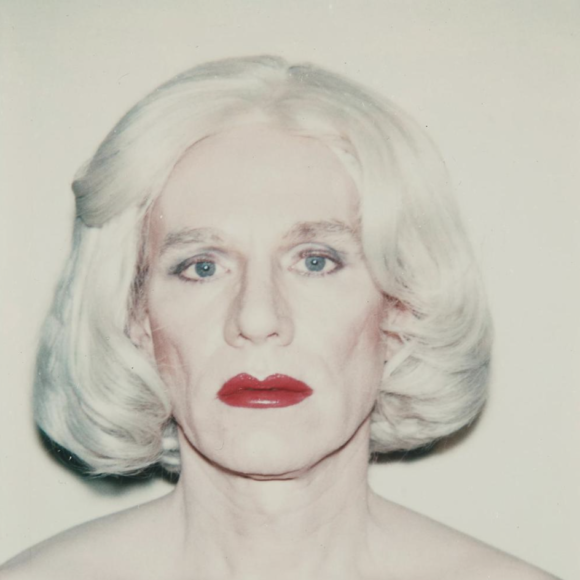

With such a big effort being made to discover a more profound artist, even works that had previously felt slight seem infused, on the occasion, with a new sobriety. A beautiful Silver Liz from 1963 has a blank expanse on one side and a garishly made-up Elizabeth Taylor on the other. It’s like a traffic light flashing on and off: from nothing to everything. The catalogue points out that Warhol chose his women for their pain, not their looks, immortalising them at moments of heightened poignancy. Taylor between divorces. Marilyn after she died. Jackie before Dallas and after Dallas. These aren’t any old icons. These are icons who’ve slapped on the make-up to hide the tears.

All these subtle shifts in emphasis are monastically conveyed in a spare selection of works. Instead of many Electric Chairs, we get just one, again. But it’s the best of them, Lavender Disaster, from 1963: a haunting purple lament upon the mechanised nature of American death, featuring a bleak execution chair, repeated in identical poses, like a postage stamp.

While finding a new profundity in Warhol is the show’s clearest objective, there’s a second corrective, too, and it’s another surprise. From the start, we are encouraged to focus on his abstraction. His taste for it. His skill at it. It’s a surprise because pop art is usually seen as a deliberate alternative to the macho splashings of the abstract expressionists. Here, though, the first thing you see upon emerging from the Whitney lift is a cavernous camouflage painting — green splashes, black splashes, brown splashes — from 1986, the year before he died.

Why it hangs in this agenda-setting position becomes clearer as the show unfolds. First you notice his hidden religiosity. Then his interest in wars, disasters, human tragedies. Then the secret or camouflaged nature of his messages: the sense that what you see isn’t all that’s there. All the while, his exquisite skills as an orchestrator of shapes and colours become increasingly evident.

The last and best room, a selection of cinema-sized paintings from his final decade, completes a journey of illumination. After Warhol was shot by the radical feminist Valerie Solanas, in 1968, the art world decided, in a rare consensus, that his quality dropped and his best years were behind him. The present display begs to differ.

Just as this contrary retrospective expanded his beginning to rewrite his story, so it expands his end. And given space to breathe, the ethereal abstracts in the final room give the survey a spiritual heft no one can have expected. The intense religiosity we had been prompted to notice at the start finds its conclusion in the giant gold crosses of his Rorschach paintings. A version of Leonardo’s Last Supper manages to return some genuine depth and poignancy to an overfamiliar image. His masterpiece as a covert believer — Sixty-Three White Mona Lisas, from 1979 — turns the Giaconda into an angelic Madonna, white as First Communion lace, then repeats her like a string of hail Marys demanded as penance by a priest in a confessional.

Have we been getting Warhol wrong? Is the Pope a Catholic?

Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again, Whitney Museum, New York, until March 31