Remarkably, the exhibition devoted to Jusepe de Ribera that has opened at the Dulwich Picture Gallery is the first exhibition in Britain to focus on him. It’s the first such show because Ribera (1591-1652) is not an artist who has naturally appealed to British tastes. If he were a type of sausage, he’d be an extra-hot chorizo. If he were a wild animal, he’d be a Tasmanian devil, or perhaps an angry scorpion.

Born near Valencia, in Spain, just as the baroque era was about to explode on art, Ribera spent most of his career in Naples, where he encountered the example of Caravaggio. Everything Caravaggio did — use real models, paint at night, make art that is sweaty with action — Ribera did too, but with the knob turned up to full. In one area, however, he outstripped his master and thrust painting into new territories: violence. When it came to violence, no artist has ever employed it, described it, revelled in it, as keenly as Ribera.

So this is the first Ribera show in Britain because the British don’t generally go to art galleries to see Johnny Foreigner being nasty. Not only does the present display focus, at last, on Ribera, it also specifically examines his attraction to gory and brutal subjects. Thus Ribera: Art of Violence breaks every polite rule of British exhibition-making. And it does so brilliantly.

The first room isn’t so much an opening as a slapping. It features two versions of one of Ribera’s favourite subjects: the death of St Bartholomew. The apostle Bartholomew was said to have destroyed some pagan idols; as his punishment, he was skinned alive. Among the Christian martyrs, no one died quite as horrible a death as Bartholomew.

In the first of his depictions of this horrible death, painted in about 1628, Ribera shows us the naked apostle, old and sinewy, like a piece of tough chicken, at the centre of a dark crowd. Grinning crazily at us from this darkness are the two executioners who are about to start hacking off his skin. Both stare straight at us, like giggling serial killers in a Dirty Harry movie, and their evil laughter gives the picture its electric charge. Ribera’s taunting executioners make you want to reach in and shoot them. But you can’t.

This is a painter employing violence for the same reasons that Hollywood movies employ it. To wake up the audience. To set the pulse racing. To cause upset and impact. And, yes, to gain notoriety. But the Dulwich show is as riveting as it is because it digs deeper than all that. It also scrabbles about in dark areas of psychology and sexual taste.

The second of Ribera’s Martyrdoms of St Bartholomew is even better than the first. Painted in 1644 by an artist who has now perfected every trick in the book, it is right up there among the most effective religious frighteners of the baroque age. This time there seem to be fewer people in the picture, just the naked Bartholomew and his two hulking murderers. It’s more intimate. More personal. One of the killers has begun cutting a strip of vivid pink flesh from the saint’s arm. The other jabs away at his leg. But this time it’s not the executioners who stare out at us from the dark. It’s Bartholomew himself.

And he does so from an exceptionally strange angle. Because his naked body is sprawled horizontally along the bottom of the painting, his head is horizontal too. Bartholomew looks at us from 3 o’clock on the clock face. No flinching. No scream. No reaction at all to having his skin sliced off. He just stares at us. As if it’s our fault. It’s a wicked piece of sweaty Catholic guilt transference.

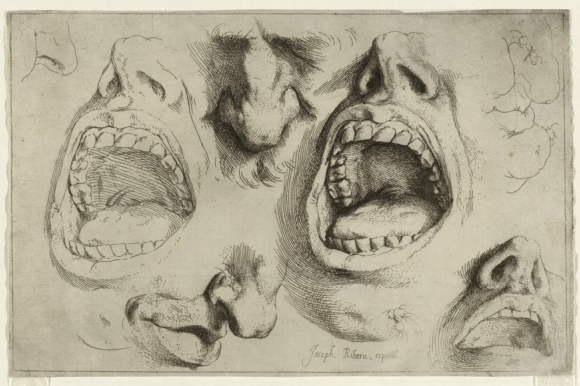

Having exposed us so successfully to Ribera’s violence, the exhibition ahead proceeds to dissect (apologies!) the causes and underpinnings in a series of rooms filled mostly with drawings and prints. The first of these looks closer at the artist’s fascination with human skin. It was what he was known for.

Nobody ever painted human skin as convincingly as Ribera. In particular, he was good at scrawny old men with sags and wrinkles, like Bartholomew, who, it turns out, is the patron saint of tanners and leather workers. A piece of actual human skin, covered in tattoos, preserved from a French prisoner in the 1850s, injects the show with a sudden shot of reality. Reality — a sense that what Ribera was painting was actually happening, right under your nose — was his best weapon. His art closed the gap between the painting and the viewer.

So successfully real did he make his paintings feel that Ribera’s own image as an artist came to be confused with his art. On no evidence at all, he was said to be angry, spiteful, murderous. It’s another reason there have been no shows devoted to him: everyone believed that Lo Spagnoletto, as they called him in Naples, was as nasty as his pictures.

Certainly, there was something edgy and a tad spooky about him. Another of his early paintings, an examination of the sense of smell, features an old beggar in rags holding an onion. There’s some garlic on the table in front of him. And a sprig of orange blossom. Amazingly, you can smell all of them — the onion, the garlic, the orange blossom and the tramp. Ribera’s realism has fooled your nose into believing him.

While violence was his chief calling card, he was also a master of an edgy eroticism. You see it especially in his depictions of the death of St Sebastian. While Bartholomew was old and saggy, Sebastian was young and beautiful — that’s why he became such a popular subject in baroque art. In depicting him, most artists focused on the arrows fired into him by the Romans when they found out he was secretly converting them to Christianity. Yet Ribera, in drawing after drawing, print after print, and especially in a fine painting from Bilbao, focuses on his armpit.

I kid you not. Image after image zooms in on Sebastian’s upraised arm and appears to bury its nose in his armpit, as if to smell it. Hah. No wonder the British have never previously mounted a Ribera exhibition. What kind of artist buries his nose in an armpit? An unusually brilliant one, is the answer.

Ribera: Art of Violence, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London SE21, until January 27