Where is Oceania? Technically, it’s the enormous slab of the southern hemisphere that stretches from New Zealand in the south to the Japanese islands in the north, and from Easter Island in the east to the Perth coast of Australia in the west. Comprising 10,000 islands, strung out across 3.5m square miles of ocean — nearly a third of the earth’s surface — it’s the most far-flung of the continents, as this show refers to it, and the one defined most actively by water.

But all that is just geography. And we don’t go to Royal Academy shows for geography. We go there for cultural reappraisals and artistic rewrites. Artistically, Oceania turns out to be a tricky territory, freighted with a vast tonnage of postcolonial guilt and accusation, across which a fierce sense of us-and-them-ism is currently rampaging.

For us, these were the enchanted South Seas, Marlon Brando country, where bounty hunters came in search of paradise, and found it, and where Captain Cook voyaged endeavour-ously in 1768 — the same year the Royal Academy was founded — to find sunny beaches and perfect palm trees.

For them, of course, Cook was an invading colonist, an alien western presence, arrived on the sandy shores for reasons that were inglorious and expansionist. And what we mistook for a paradisiacal existence was actually a demanding and complex lifestyle, where survival depended on great ingenuity and skill, and where the gods were constantly called on to affect and save.

Across this big divide in perception, the Royal Academy’s Oceania exhibition seeks nimbly to skip, with varying degrees of success. It ends up as a valuable and beautiful show, but that’s not how it starts. Indeed, in its effort to be both a scholarly celebration of Oceanic art and a display that causes no cultural offence, this well-meaning event frequently feels as if it is walking on eggshells.

The opening vista consists of a huge blue tarpaulin, hanging like a giant hammock from the Academy roof, made of “polyethylene and cotton thread” by the Mata Aho Collective in New Zealand. It’s big. It’s blue. But that’s about it. Artistically, it’s inert, and no amount of wishful thinking can turn it into anything other than a big blue tarpaulin.

On an adjacent TV screen, the insistent drone of an American accent turns out to belong to the poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, a California-educated Marshall Islander, whose advice — “Tell them our islands were dropped/ from a basket/carried by a giant” — might have felt more authentic had it not been delivered in an irritating San Franciscan campus drawl.

Thankfully, after this weak opening, in which antsy contemporary art is overpromoted to the front of the queue, the show gets properly into its stride with a room devoted to the traditional sailing skills of the Pacific Islanders and the marvellously inventive carving with which they covered their canoes and paddles. The only continent linked by water rather than by land, Oceania has always tested its inhabitants in unique ways, and the artistic responses to these maritime conditions have an energetic busyness to them.

A line of paddles from New Zealand, the Solomon Islands, Dibiri Island — each strikingly different from the others — offers a feast of crowded carving. A beautiful “navigation chart” from the Marshall Islands — an abstraction of thin sticks studded with snail shells — plots the movement of the ocean in a delicate coded form that must have required huge experience and knowledge to decipher. We are in the hands of great navigators, brilliant readers of nature and thunderously brave travellers across the oceans.

The show ahead is divided into rather fuzzy themes. There’s a gallery devoted to Oceanic ceremonies and the things made for them. Another looks at the giving of gifts and the importance of the act; a third at the encounters with Europe and the arrival of “empire”. As a route map, it’s not especially legible, and with 10,000 island names to remember and an exhibition-long desire to privilege native languages, the show seems often to be coming at you from all angles.

Most of the exhibits date from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, which places them rather awkwardly in the postcolonial period and had me wondering sometimes about their authenticity. Were they, like so much African art of the period, produced specifically for export and the tourist trade? Or were they genuine native creations used unselfconsciously in daily life?

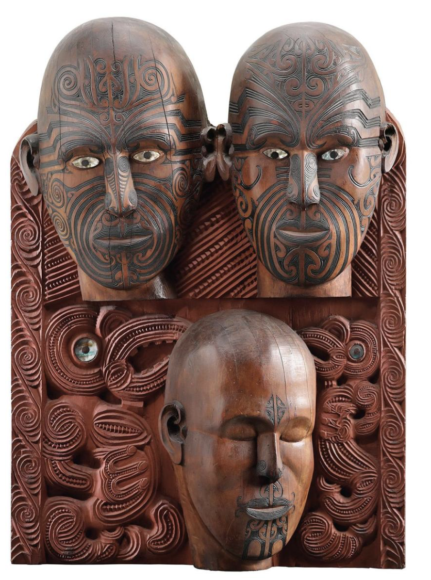

The oldest object here, a door arch carved with a superb central tiki, or god image, survives from as long ago as the 14th century and was found buried in a bog in New Zealand in 1920. In an event packed with overcrowded carvings, this marvellous early tiki has a striking simplicity, a sense of pent-up power, as rare as its early-14th-century date.

Wood may be a gloriously flexible art material — the show keeps proving it — but in survival terms, it is no match for the stones and marbles available to other civilisations at the time. There’s a suspicion, therefore, that we are admiring the sequel rather than the original, and that a long history of Oceanic creativity has been lost in the turbulent waters of history.

On the plus side, the unfixed and demanding artistic conditions encouraged adventure and ingenuity. Among the materials used to fashion the necklaces, masks, idols and headdresses on show, I noted down shark vertebrae, sea-urchin spines, whale ivory, flying-fox fur and the skeleton of a pufferfish. In the shifting and perilous conditions in which Oceanic artists had to work, uncommon amounts of inventiveness and transformation were called for.

Especially in the creation of things to worship. The gallery devoted to Oceanic gods is the first of the show’s highlights. In imagining the different forms of divinity needed to guide them through their fragile Pacific lives, the ocean islanders were at their most inventive. Every island came to different conclusions about its idols. From the looming moai of the Easter Islanders to the spare and streamlined deity figures of the Caroline Islanders, the gods of Oceania were a fabulously varied and powerful cast.

The show’s second highlight is — hallelujah — one of its contemporary exhibits: Lisa Reihana’s brilliant moving panorama In Pursuit of Venus (Infected), to which the exhibition has rightly devoted its central gallery. Readers with sharp memories will remember that I reviewed it at last year’s Venice Biennale, where it was one of the best exhibits. It looks even better here.

Based on some French 19th-century wallpaper extolling the sunny pleasures of the South Seas, Reihana’s wall-sized digital update tells the unfolding story of the Pacific Islanders before, up to and after the arrival of Captain Cook. Created with a brilliantly achieved mix of live action and cunning animation, it’s totally engrossing: one of the signature masterpieces of our times. Don’t miss it.

Where Oceania is a bit patchy, the Turner Prize 2018 exhibition at Tate Britain is thoroughly consistent. From beginning to end, this soul-crusher of a show is unusually awful.

Consisting only of video art, and weighing in at eight or so hours of nocturnal viewing, the relentlessly bleak display is devoted entirely to evening-class politics. With a show as grim as this, there are no winners, just a sliding scale of awfulness.

The least bad is Charlotte Prodger, whose biographical complaint about the sexual misunderstandings she has faced as a lesbian shelves its narcissism now and then to confront us with a nice image filmed on her iPhone. Second least bad are Forensic Architecture, a collective of non-artists based at Goldsmiths, University of London, who use effortful slo-mo and dreary computer graphics to relive an Israeli attack on a Bedouin village. Second worst is Luke Willis Thompson, a New Zealander who takes giant shots of people’s faces. Yes, that old trick.

The worst exhibitor is Naeem Mohaiemen, whose 89-minute film about “the power struggle between the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in the 1970s” is even duller than it sounds. When did art turn into this?

Oceania, Royal Academy, London W1, until December 10; Turner Prize 2018, Tate Britain, London SW1, until January 6