There have been many busy collectors of art whose activities have made Britain a better place, but in my estimation there have been only three who redirected our culture and changed our taste. The first was Charles I, whose lavish spend on great European art finally put paid to Tudor black-and-whiteness and yanked Britain into the baroque age. (What did we do to thank him? We beheaded him.)

More recently, there was Charles Saatchi, who, against all the odds, turned Britain from a nation of modern-art haters into a pram-pushing tide of enthusiasts who flood to Tate Modern to sample its winning mix of art and foyers. Who would have thought it?

In between these two potent accumulators, there was a quieter figure who opened the nation’s eyes to the wonders of French post-impressionism, and who, by doing so, gave 19th-century stiffness its marching orders, banged some nails into blimpish Victorian values and softened the stubborn Great British resistance to exciting continental ideas. Thank you for all that, Samuel Courtauld (1876-1947).

Courtauld made his money in textiles. He was, I am pleased to read, a progressive employer as well as a collector of vision. His taste for art dated back to a visit to the Tate in 1917 and, once opened, the window to sunshine led him quickly to Cézanne, Seurat and Gauguin, whose work he began collecting with an extraordinarily good eye.

In 1931, he founded the Courtauld Institute, still the most prestigious art-history college in the world. He also endowed the Courtauld Fund, a generous slab of money with which the Tate and the National were able to build up their important holdings in post-impressionist art. Who paid for Seurat’s Bathers? The Courtauld Fund. Who paid for Van Gogh’s Sunflowers? The Courtauld Fund.

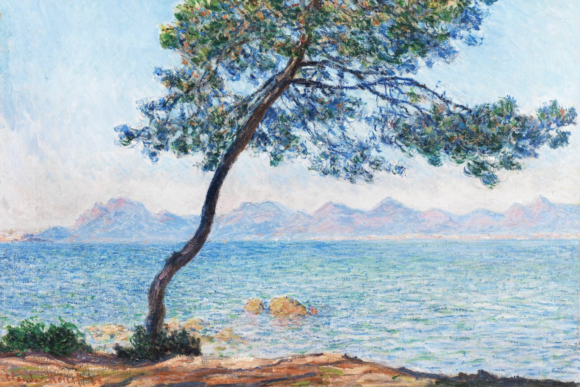

That was the public contribution. Privately, he put his money where his nose was and collected a high-quality hoard of impressionist and post-impressionist pictures, which he left to the Courtauld Gallery, located in Somerset House, on the Strand. As a result, it houses the choicest array of post-impressionist pictures outside France.

The Courtauld Gallery has now closed its doors for an ambitious two-year restoration. But worry not if you haven’t been there, because most of the finest pictures have journeyed along the Strand to the National Gallery, where a show entitled Courtauld Impressionists: From Manet to Cézanne is uniting the best things acquired through the Courtauld Fund with the best things usually on show at the Courtauld Gallery. The result is an almost complete idea of what Samuel Courtauld did to British taste.

I say “almost complete” because several of the absentees from this show are a tangible loss. Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, that masterpiece of symbolic narcissism that usually hangs so prominently at the Courtauld, is missing, lent to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. So is Cézanne’s finest Mont Sainte-Victoire, departed to events elsewhere. At first I thought Van Gogh’s Sunflowers had gone as well, but they are actually hanging nearby, in the National Gallery foyer, in a confusing blurring of the show’s agenda. Why there, not here?

The missing Sunflowers are part of a wonky ringing of the bells that continues in the display itself. It is, of course, a gorgeous parade with fabulous things in it. There’s a row of Cézannes. A wall full of Renoirs. A line of Manets. Seurat’s Bathers looms up on one wall. Daumier’s Don Quixote looms up on another. You get a clear sense of Courtauld’s importance as a collector, and an immediate feel for the numbers involved.

Despite the presence of all these highlights, something isn’t right. The event seems spotted with awkwardness. Its excitement feels muted. There are little slippages from the true. Hard as it is to believe, this change of context for the Courtauld pictures has managed somehow to diminish their impact. I mean that literally. In the soaring upstairs exhibition rooms of the National Gallery, the art looks smaller than it does in the converted domestic interiors of the Courtauld. Much smaller, in some cases.

Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, universally accepted as a high spot in his oeuvre, sits in my thoughts as a big Manet: hefty in size as well as import. But here it looks unexpectedly modest, unassuming, just a mite larger than the nearby Music in the Tuileries Gardens, another fine Manet, which usually hangs in the National Gallery, and which I have always thought to be small.

Or what about the Gauguins? The magnificent Nevermore, to my eyes his best and most haunting Tahiti painting, usually dominates its surroundings with its heady mix of psychology, sensuality and innocence. But here it is part of a parade of Gauguins that feel curiously flat. Even the magnificent Te Rerioa, the ultimate South Seas dream picture, seems diminished. The same happens to the Renoirs.

Studied scientifically, these unexpected aberrations of scale would no doubt reap important information about the presentation of art in galleries: what changes it, how to exploit it. In the short term, the teenier presence of the Courtauld pictures seems to affect the rhythm of the show and to blunt its excitement.

It’s a feeling exaggerated by other exhibition decisions. The National’s current director, Gabriele Finaldi, has been busy reorganising the gallery hang, and one of his most obvious changes has been the introduction of noisy signage that directs you left and right from the Caravaggios to the Titians, and so on. I can see exactly why he has done it. We all need help in navigating large collections. But Finaldi’s mapping is intrusive and clunky. Frankly, the glaring presence of these big directional signs has the effect of destroying some of the magic of looking at art. The inner peace of the National Gallery is being disturbed by the aesthetics of the motorway.

Something similar happens in the Courtauld show. In front of every artist, a huge white circus act of a sign, with a photo of Samuel Courtauld’s house on the back, tells us about the art and its acquisition. It’s useful information. But there’s enough space on these double-height posters to add a couple of books on the subject. Again, the crude ambition to keep the audience informed seems to be working against the better gallery ambition of keeping us enchanted and ecstatic.

However, I have nothing but enthusiasm for another of Finaldi’s innovations, which is the opening up of the restoration process at the gallery by turning it into a spectator event. Restoration is tricky, often misunderstood and recurrently controversial. What should you take off? What should you repaint? What shouldn’t you repaint? The secrecy that has traditionally attended the conservation of notable pictures has led to all sorts of anguish.

But restoration is also intrinsically fascinating, and the gallery-going audience has now grown rather interested in it. I recently filmed the restoration of Van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb — the giant altarpiece from Ghent that George Clooney tries to steal back from the Nazis in The Monuments Men — which was taking place in a specially constructed glass chamber in Antwerp. All day long, a large crowd pressed its nose against the glass, eager for a glimpse.

This is the interest that Finaldi has begun to exploit by allowing us unprecedented access to the restoration of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as St Catherine of Alexandria, in a series of informative vodcasts featuring the National’s curators and restorers. You can see it on YouTube.

St Catherine was an early Christian martyr, tortured by the Romans, who drove a spiked wheel over her. You can see the spikes on the left, looking excellently evil. But, as always with Artemisia, the facts of the painter’s own life — raped at the age of 17 — seem to infect the mood of her art. Recently acquired by the gallery, Gentileschi’s compelling selfie is a powerful blend of Catherine’s story and her own.

I can’t wait for the restoration to be finished. In the meantime, I was allowed into the conservation studio where the careful cleansing was progressing inch by inch. How exciting.

Courtauld Impressionists, National Gallery, London WC2, until January 20