Houghton Hall is a glorious country house near the Sandringham estate in Norfolk. I have no idea if Her Majesty often pops over, but if I were her, I would. Begun in the 1720s for Britain’s first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, the superb house was designed by Colen Campbell, Britain’s greatest Palladian architect. The interiors are by William Kent, the finest interior designer of the times. And, although the gardens are not by Capability Brown, they are by Charles Bridgeman, his pioneering predecessor, who does not get the attention he deserves.

Houghton is, therefore, the height of excellence in the country-house sphere. Interestingly, though, its current owner, the 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley, has a taste for contemporary art. Three years ago, he mounted a dazzling exhibition here devoted to the American light maestro James Turrell. And this year the exquisite Georgian pile of the Cholmondeleys has been pressed into the unlikely hands of that noisy serf from Leeds, Damien Hirst.

There’s an element of rough trade to this unexpected transaction. The elegant Houghton surroundings belong to one set of cultural values. Hirst belongs to another. By putting on a Hirst show, the current marquess isn’t merely sharing his stately grace with a hardened contemporary presence. Frankly, he is tying himself to a bed and allowing himself to be rogered by it.

The show, Hirst’s first in an English country house, features paintings and sculptures scattered about the house and gardens. It’s the adventure-trail approach, and it can never go fully wrong, because wandering about Houghton Hall is a joy, Hirsts or not. As a frame, a situation in which art is displayed, this fine slab of Georgian extravagance is endlessly pleasing. That’s where the rogering comes in.

When contemporary art is shown in stately homes, there is always a clash. Often — usually — the house wins and the art looks awful. One of the ghastliest such meetings was the Michael Craig-Martin exhibition at Chatsworth House in 2014. From start to finish, Craig-Martin’s Paperchase pinks clashed with Chatsworth’s baroque greys. The mansion looked superb. The art looked crass.

This isn’t what happens at Houghton Hall. Say what you like about Hirst — and everybody has done — he lacks neither cheek nor ambition. And the sense here is of an artist seeking not to fit in with the existing circumstances, but to dominate them, overwhelm them, make them his. He doesn’t succeed everywhere. But it does work in places. Which, given what he is up against at Houghton Hall, is a genuine achievement.

We start inside with the pictures. Above the mantelpieces and doorways, at the ends of the vistas, up on the walls, over the beds, in the corners of the library, everywhere you look in these elegantly subfusc Kent interiors, a crowd of bright paintings has elbowed out the family portraits and the classical mythologies. All the upstarts are “spot paintings” — coloured dots arranged on white backgrounds. But these are not like Hirst’s old spot paintings — precise essays in pictorial engineering, carefully calculated in tight grids. He has stopped doing those.

Instead, the new spot paintings, what he calls his Colour Space pictures, are a much looser polka dot, with blobs of colour bumping happily into each other all round the canvas. Where the old spots were rigorous and immobile, the new ones are wild, misshapen, drippy. It’s a very different effect. The spots have gone on the dodgems.

So, instead of the 2nd or 3rd or 4th Marquess of Cholmondeley staring down at you from the picture rails, you now have cascades of boisterous dots pouring out of the frames like an invading army from another dimension. It’s all a bit Doctor Who. In some pictures, the dots are tiny. Elsewhere, they are huge. Some form horizontals; others, verticals. And although they cannot help but clash occasionally with the gorgeous damasks on which they now hang, it’s also true that they often do not. Hirst has managed to turn the entire house into an installation.

With no less than 46 of the new dot paintings scattered about Houghton, it gets a bit relentless. The ones I remember are the ones that look different: the bold vertical of blousy dots propped up on an easel in the library; the fine mesh of tiny ones hanging sweetly above a four-poster bed. But all are unmissably cocky, and the overall effect is of a successful putsch. The past, nil; the present, one.

Outside, meanwhile, in Charles Bridgeman’s Georgian reordering of nature, a selection of Hirst sculptures from various phases of his career attempt to lord it over the gardens as the dot paintings lord it over the house. But with the grounds being so extensive and gorgeous, the struggle is more equal, and the results are more mixed. Some sculptures work. Others do not.

Among the weaker contributions are two white horses popped down on the lawn in front of the main house: a unicorn and a Pegasus; one with a horn, the other with wings; one called Myth, the other called Legend. Both are life-size and raised on tall plinths, in the manner favoured in the past for posh equestrian sculptures. At least they are from one side. From the other side, both have had their gleaming white coats removed, revealing their gory inner workings — muscles, bones, ligaments — in the manner of a George Stubbs anatomical drawing.

What Hirst is after here, I suggest, is a contrast between dreamy legends and harsh reality: clouds v blood. The white horses belong to a mythic breed that exists only in the country-house imagination. But with typical brutality, he strips away their skins and reveals their gore, not to shock us, as so many are so keen to accuse him of, but to remind us of their equine mortality. You can stick a horn on a horse, but you’ll never make it fly.

Why don’t they work? Because unicorns never work. Unicorns always arrive at the battlefield saddled with My Little Pony atmospheres that never make a convincing transition into profundity. In mythic terms, they are a step too far into the world of princess kitsch. And, even though kitsch is one of Hirst’s deliberate materials — something to be played with and moulded — the horsey sculptures at Houghton are a touch too yucky.

Far more successful are the giant human figures looming above the trees, away from the house: a pregnant woman, called The Virgin Mother, and a huge masculine torso, called Temple. These towering human colossi have had their skin removed in places, revealing their gory innards. So, again, there’s a sense of myth being torn aside to reveal reality: something imaginary is being compared with something corporeal. All round Houghton Hall, in niches, on balustrades, up staircases, you can find examples of classical sculpture from the past — Apollos and Venuses, marble gods and stone nymphs — whose delicate ancient presence is being challenged and monstered by Hirst’s garden giants. As I said, it’s quite a rogering.

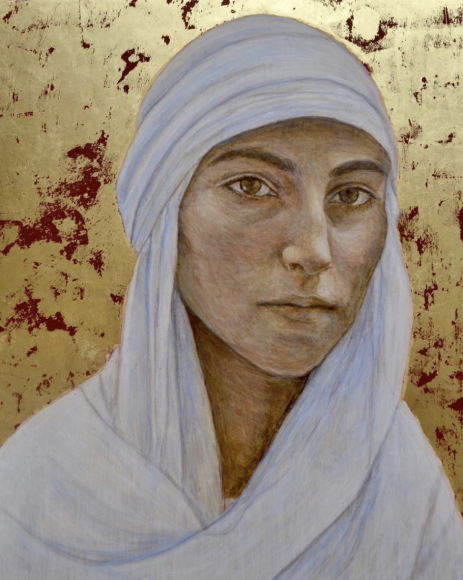

For something completely different, and altogether more wholesome, and more readily supportable, I wish to direct some praise at a small show I saw in the Upper Waiting Hall of the Houses of Parliament last week, by a young artist, Hannah Rose Thomas, who unveiled a series of portraits of Yazidi women painted as a result of a trip she took to Iraq, where she met the survivors of rape, torture and imprisonment.

The show brings together self-portraits made by the Yazidi women themselves with Thomas’s sad and exquisite recordings of them. Next to each Yazidi woman is a short account of their sufferings under Isis. As I sobbed my way from one grim life to the other, I felt increasingly certain that this was beautiful art doing beautiful things in a terrible world. Bravo, Hannah Rose Thomas.

Damien Hirst, Houghton Hall, Norfolk, until July 15; Hannah Rose Thomas, Houses of Parliament, London SW1