Cézanne exhibitions used to be relatively frequent, but that was in the days before the art world was annexed by the entertainment industry —when we went to art galleries to be educated and moved rather than to have a go on the swings. So the first thing to say about the show devoted to Cézanne’s portraits that has arrived at the National Portrait Gallery is that it is a welcome display filled with marvellous pictures.

Unfortunately, the second thing to say is that it could have been better. Indeed, it would have been better in the aforementioned days of yore, when galleries were devoted to deeper scholarship. The pictures are present here that could have made this a momentous event. But the use they are put to manages to turn a heavyweight collection of art into a lightweight set of understandings.

The focus on Cézanne’s portraiture is fresh. This is the first show, I read, to have done it. Most Cézanne exhibitions have looked at his pioneering landscapes or his shape-shifting still lifes — the celebrated apples with which he vowed “to astonish Paris”. But throughout his career, Cézanne also painted himself, his family and his friends. And what we have here is an attempt to put these paintings of people into telling clusters that bring new insight into his art. Or, rather, that is what we should have had here.

The problems commence with the first picture and an opening caption that describes “Cézanne’s practice of portraiture”. Cézanne didn’t have a “practice” of portraiture. “Practice” is a piece of art-world jargon borrowed from the medical profession that most sensible galleries have banned from their captions because it turns off visitors. Cézanne “painted” people — he did it often — but it wasn’t portraiture as we usually understand it. At no point did his tussles with people turn into anything as ghastly and jargonistic as a “practice”.

Also frustrating is the shallow use made of the show’s first painting, the celebrated portrait of Cézanne’s father, lent by the National Gallery of Art in Washington. It’s a landmark image. Big and muscular. What a coup to have it here. It presents Cézanne Sr sitting in an armchair, reading the unlikely literary journal L’Evénement, in which Cézanne’s childhood friend Emile Zola published his defence of the artists rejected by the French Salon of 1866.

The scene is unlikely because Cézanne’s conservative father was the last person on earth who would have pored over L’Evénement. This is like showing Jacob Rees-Mogg engrossed in The Guardian. A send-up. A portrait with satirical intent. A glimpse into the complex wickedness of Cézanne. None of that wicked intent is investigated here or foregrounded.

The dad painting has recently been cleaned, to reveal a significantly brighter presence and a whole new side to it. If you have been to Washington to see it, you will know the right-hand edge was previously black and impenetrable. But the cleaning has produced an unexpected view into Cézanne’s studio, where a pile of canvases are stacked against a wall. Hah! If you also look up at the top of the doorway, and shift sideways till the slanting light outlines the pentimenti, you will see there was previously what looks like a giant mirror in the background. At some point, this was a picture that played Velazquez-style games with reflections. Hah! And stepping sideways to see the raking light tells us the shape of the chair was also radically altered. Hah! So much could have been noticed if this really were an event with pioneering scholarly ambitions.

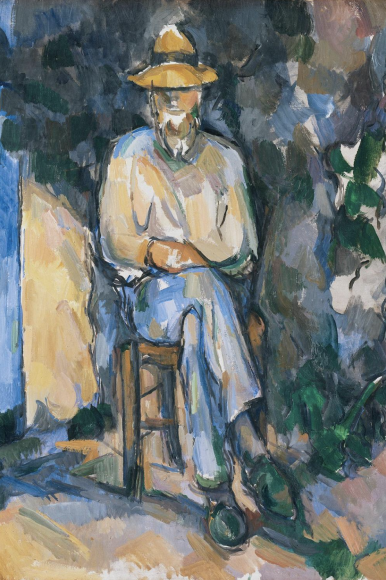

With loans as impressive as these, however, useful points are, of course, made. The room devoted to what Cézanne called his “couillarde” pictures — from the French word “couilles”, meaning “balls” — examines how the dark, blunt, palette-knife technique he employed in his “ballsy” phase laid the ground for the directional brushstrokes and careful cubistic construction of the mature Cézanne. To produce the “couillardes”, Cézanne wielded his palette knife in a fashion more commonly employed in the patting of butter. What we are actually watching here are the origins of cubism.

It’s a helpful insight. Much of what follows feels timid, uninformed and laced with contemporary prejudices. It’s particularly obvious in the discussion of Cézanne’s portraits of his lover and eventual wife, Hortense Fiquet. She’s a recurrent presence and the sitter in some of his most graceful and touching portraiture. The Hortense pictures are the highlight of the show.

Yet the caption writer seems continuously to see something in them that simply isn’t there. There is much discussion of Cézanne’s misogyny, of these being “tough” portraits, of a process that “defeminises” Hortense. To my eyes, none of that happens. These are only “tough” portraits if they are misunderstood.

We know from the rest of Cézanne’s output that his overriding ambition was to update the Old Masters: to produce a contemporary art that was as noble and permanent as the art of the museums. That was perhaps what was going on in the Velazquez-style reflection games preserved as ghosts in the portrait of his father.

We know also he became increasingly religious, to the point of mania, and that the influence of the medieval statuary in the porch of the cathedral in Aix where he worshipped is responsible for the strange elongations and gothic simplifications he introduced into his portraits. Even the way his sitters sometimes “lean” to the side was inherited from the gothic porches at Aix. Far from being an attempt to “defeminise” Hortense, these increasingly simplified portrayals constitute a campaign to turn her into a feminine icon: a secular Virgin Mary. The oval face and the simplified forms are seeking to reverse the Provençal clock and return to an age of idealised femininity. Hortense doesn’t smile in Cézanne’s portrayals not because she is unhappy or defeminised, but because Madonnas don’t smile.

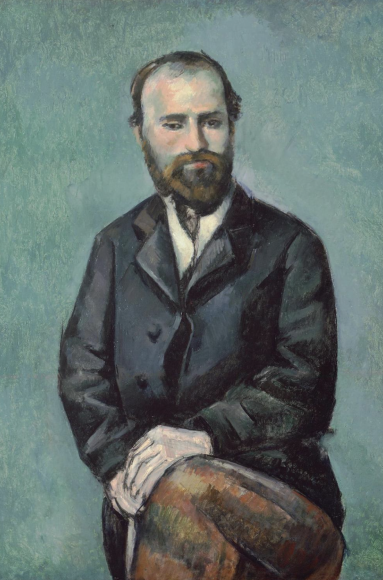

While the Hortense pictures are the highlights, the assorted portrayals of men jump about with a stylistic restlessness that is often surprising. Early in the show, two portraits of Antony Valabrègue, painted just a few years apart, appear to record a different man. In one, he’s thoughtful and chunky; in another, stick-thin and blank.

Even when painting himself, Cézanne struggles with the basics of achieving a likeness. The two versions of him in a bowler hat are so different — one is so good, the other so bad — that I am not convinced the second is by him. Look how clumsily the bowler hat sits on the head. His attempts to paint chaps in studies and collectors in sitting rooms led to nothing substantial, and were often unfinished. Not surprisingly, he received no portrait commissions from strangers and everything here was painted for himself. With the men, as with the women, the most successful results are not portraits in any clear sense, but idealised portrayals of masculine figures whose job, you feel, is to represent a type rather than individuals.

The ragged journey comes to a ragged conclusion in a final room that looks like the handiwork of half a dozen painters. Only a marvellous last self-portrait, Cézanne sunken eyed and worn out, reaches the high notes reached so regularly earlier in the show. Unmissable? Yes. A missed opportunity? Yes.

Cézanne Portraits, NPG, London WC2, until Feb 11