There are two hefty reasons why there is no award for Most Decrepit Painter in the History of Art. The first is because such an award would be squalid and demeaning, and not even the art world would stoop that low. The second is that the result would be a foregone conclusion. Year after year, the prize would go to Chaïm Soutine (1893-1943).

Where to start? Perhaps with the story of his earache. After months of scratching his head and complaining of the pain, Soutine — who had arrived in Paris from Lithuania in 1913 — finally went to the doctor, who discovered a nest of bedbugs in his ear. They had been living there for years. Another good one is the tale of him buying the carcass of a dead cow and hanging it in his studio to paint. A couple of times a week, he’d go back to the butcher for fresh blood to pour over the rotting corpse. It was only when the stench and the flies got too much for the neighbours that he was forced to remove it.

There are scores more stories of this ilk about Soutine. His bohemian Parisian friends — Modigliani, Picasso — enjoyed repeating them and adding details. From the start, there was something mythic about him, something archetypal, a sense that he embodied the wild artistic presence that knows no bounds. Plenty of good painters in the School of Paris were down at heel. None was as down at heel, nor, indeed, as good, as Soutine.

The Courtauld Gallery, which has now mounted a marvellous exhibition devoted to his portraits, is far too dignified an institution to dwell on his squalor in any of the paperwork that informs this show. Its approach, a noble one, is to ignore his decrepitude and present him as a thoughtful and empathetic observer of the human condition. Which he was. It is left to lowlifes like me, therefore, to flavour this learned understanding with a sprinkling of biographical soilage. Not because it undermines Soutine, but because it helps convey the excitement of his presence. It’s an excitement like no other in art. There is something primal about his touch, something that takes us back, back, back, to the roots of all creativity.

The show is the first to focus on his portraits. More than that, it is the first I remember seeing about him in Britain, full stop. I would not call him forgotten, but I certainly would call him undervalued. Unlike his buddy Modigliani or his opposite, Chagall, he is not one of those pretty School of Paris painters who make great fridge magnets. His name recognition is surprisingly low. And his fierce energies and elemental artistic presence seem to frighten off modern curators in the way that bushmeat frightens vegans. Unless, of course, they are the brave curators of the Courtauld, who always do things differently. In autumn 2018, the gallery is closing for two years for a shape-shifting refurbishment. It will be a huge loss.

Portraiture is the least valued of Soutine’s achievements. When you think of him, you think of the turbulent landscapes of Céret being blown away by Hurricane Chaïm, or the hanging beef carcasses oozing crucifixion blood. Mood-wise, he was a demented Rembrandt. Style-wise, he was Van Gogh taken to extremes. But by focusing on his portraits, the Courtauld hopes to make it clearer that lurking beneath the barroom brushstrokes was a respect for tradition, an approach and a vision learnt from the Old Masters. (Warning: that is not what you will come away with. What you’ll come away with is the feeling that you’ve been in a cage with a Tasmanian wolf.)

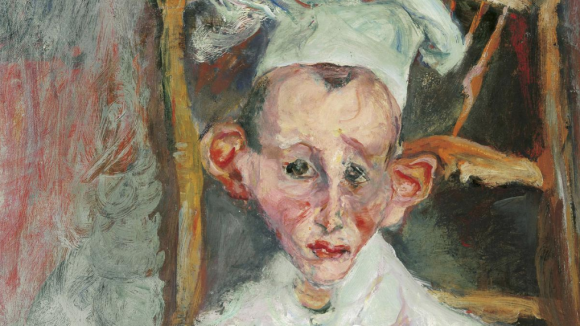

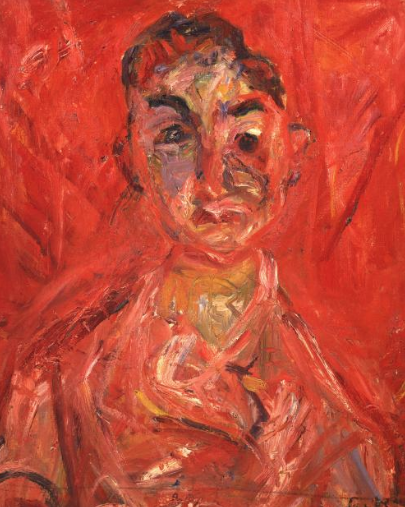

The 21 paintings on view represent a substantial slab of his best work as a portraitist. Right from the start, there’s a sense here that this is not portraiture as we generally know it. This is something fiercer. It’s as if all these sitters, like Christ on his march up Calvary, have pressed their faces into Veronica’s veil and left their likeness on it. It’s most obvious in the portrait called Butcher Boy, from 1919, which looks initially as if it really is painted in blood. Indeed, the red backcloth to the harshly staring face was a curtain used by the local butcher in Céret.

So there’s a religious air. But it isn’t churchy. It’s deeper, more basic. A sense of sanctity. A value placed on life. By focusing on his portrayals of humble hotel workers — waiters, bellboys, pastry cooks, maids, valets — the exhibition locates Soutine on the side of the proletariat in the great battle of life. And as nobody here is named, they all feel as if they stand in some way for the rest of us.

Why waiters, bellboys, pastry cooks? According to the catalogue, the era under consideration, the 1920s and 1930s, was the heyday of the grand hotel in Paris: an epoch when the difference between the haves and the have-nots was most obvious. Unseen, unpainted by Soutine, are the moneyed international guests who filled the lifts manned by the bellboys and ate the food cooked by the pastry chefs. Soutine’s waiters and maids, like Cézanne’s farm labourers, are from a working class making its debut in art.

So it’s quickly obvious where his sympathies lie. The two shivering chambermaids who flank the door to the second gallery are painted on tall, thin canvases that seem to amplify their nervousness and sense of subservience. This is human empathy on a truly Rembrandtian scale. If a wind blew, the etiolated canvases would bend. What a marvellously pioneering touch to involve the shape of the picture in its meaning.

But the affection for uniforms he also displays here — the bright red outfits worn by the bellboys, the snappy waistcoats of the waiters, the whites of the cooks and chefs — strikes me as an altogether happier concern. The spectacular bellboys, in particular, allow Soutine to unleash a mass of crimson on us that is more usually found in fields of poppies. It’s genuinely thrilling.

His pastry chefs are supposed to be clothed in a functional white. But Soutine doesn’t do functional white. It’s as if he has deliberately set himself the task of finding colour where others see only blankness. Peer into the white aprons of his hotel cooks and you will find swirling rainbows of glorious reds, blues and yellows. What a magnificent colourist he was.

And what a generous eye he had for the quiet face that speaks volumes. The timid Pastry Cook of Cagnes, an early example from 1922-23, clutches a cooking cloth to his tummy like a jilted lover clutching a cushion. Look at his sad Prince Charles ears, sticking out hopelessly on either side, like indicators on a car, signalling his failure.

There’s a lot of pathos in this show. A lot of projection. But what it is most full of is blasts of pictorial courage that make the efforts of other painters of the epoch feel tepid.

Which brings me back to his origins. As I said, this is not an event that dwells on biography, but we surely understand Soutine better if we remember that, like most of the little people he portrays, he was an immigrant, an outsider, born into profound Jewish poverty in a grim Lithuanian corner of the Russian empire. One day, the sons of the village rabbi caught him drawing and beat him up brutally for breaking the second commandment, which forbids the making of graven images. So his mother sued the rabbi, won the case and used the money to send him to art school.

It is one of the great art parables.

Soutine’s Portraits, Courtauld Gallery,

London WC2, until Jan 21

● On another topic, the National Gallery has had a rehang. Dutch and Flemish art of the baroque age, in which it is immodestly strong, has been swapped with French art, in which it is substantially weaker, creating a super-annexe of Dutch and Flemish masterworks at the top of the gallery.

Rubens has been foregrounded. So have Van Dyck and Rembrandt. Indeed, the giant Van Dyck of Charles I riding out on a pale horse that always hung in the baroque rooms at the centre of the gallery has been moved to the new super-annexe, where it stares across at Rembrandt’s equestrian portrait of Frederick Rihel, in a mighty horse-to-horse confrontation.

The aim, I read, is to play to the gallery’s strengths and draw clearer outlines around the giants in the collection. I suppose I’ll get used to it. Until then, Rubens feels diminished, Van Dyck looks removed and the French art transported to the centre of the gallery seems too quiet for the job.