The other day at Sotheby’s in New York, a painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat entitled, with typical art-world dumbness, Untitled, sold for $110.5m. It was the highest price paid at auction for an American artist and proved once again, should anyone need further proof, that the world of art has turned into something disgusting. How many African lives in how many African villages could have been saved for that kind of throwaway money?

The Japanese clown who bought Untitled, Yusaku Maezawa, a mail-order tycoon who used to be in a band, said: “When I saw this painting, I was struck with so much excitement and gratitude for my love of art.” He didn’t dwell on the picture’s meaning, its importance or its legacy. This gurgling schoolboy of a billionaire bought Untitled at such great expense because it validated his own cheap taste in art.

None of this is touched upon in Basquiat: Boom for Real, a noisy hagiography at the Barbican that bills itself as “the first large-scale exhibition in the UK” of Basquiat’s work. In language that the Maezawas of this world would understand, the show airily describes him as “one of the most significant artists of the 20th century” and promises a radical new reading of his achievements.

I went into it chuckling in avuncular fashion about the hype. But I came out angry. OMG. This really is what the art world has become: a shallow, uneducated, disingenuous, over-moneyed, rapacious chewer-up of proper artistic values.

What happened to Basquiat wasn’t his fault, of course. He was just a pretty kid from Brooklyn who fell into the grotesque company of the New York art crowd. He started out as their enemy, but he was easy to disarm. First they welcomed him. Then they got him drunk. Then they made him famous and exploited him. Indeed, they’re still doing it today. He isn’t around to see it because he died of a heroin overdose at the classic rock-star age of 27. And nothing drives up prices quite as successfully as an early death. The art world certainly got what it wanted from Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-88).

Predictably, the show begins not with his art, but with him: a film of Basquiat dancing sexily in his studio to the sound of the classic bebop he loved. Had he been short, fat and spotty, none of this would have happened. But he wasn’t. He was cute and wild. And the New York art world took him in and fed him like a pretty puppy found on the street.

In his first incarnation he was a graffiti artist. New York at the end of the 1970s was a dark and troubled place. The city was bankrupt. Drugs were everywhere.

I remember walking through the East Village on my first visit to the Rotten Apple and seeing five burning cars in one street. The graffiti that began turning up on the sides of trash cans or layered along the lengths of the subway trains was an angry cry for attention, a desperate ripping of the fabric by a disenfranchised urban class with nothing to look forward to.

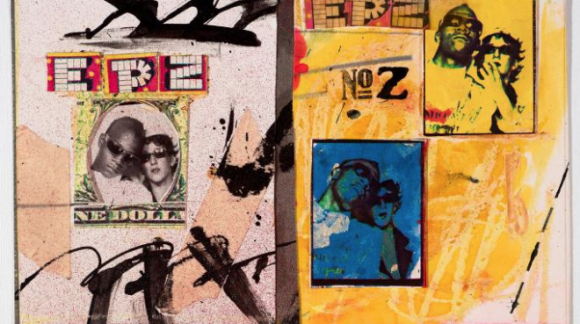

That wasn’t what Basquiat’s graffiti was about, though. He called himself SAMO — it stood for “same old shit” — and made himself poetically ubiquitous. An alcove filled with photos of his sprays shows SAMO getting himself noticed by taking pops at the art world. “SAMO as alternative 2 ‘playing art’ with the ‘radical chic’ sect on Daddy’$ funds” he scrawled on the walls of SoHo, the trendiest art district in town, where the radical chic set playing art with Daddy’s funds couldn’t miss him.

His aims were different from the aims of the other graffiti artists. They wanted to be noticed by whoever was passing. He wanted to be noticed by people who owned galleries. Seeing Andy Warhol having lunch in SoHo one day with the curator Henry Geldzahler, Basquiat interrupted them and sold Warhol a handmade postcard. By the time I first encountered him, at the Kassel Documenta in 1982, he was 21 years old and already rubbing shoulders with Joseph Beuys. Nothing was properly earned. It was all on a plate. The art world was hungry for wild new blood. The wild new blood was hungry for the art world.

Full of music, films, books and photographs, as well as paintings, the Barbican show has an ambition to present him as a multidimensional artist: not just a painter, but a poet, performer, musician and activist. This is the “revolutionary angle” it boasts about adopting. And it is certainly true that in his brief life he managed to spew out a lot of stuff. By bringing together his notebooks, scraps of drawing, homemade postcards, photos of his graffiti, the show has no difficulty packing 14 rooms with his outpourings. Thank heavens he wasn’t the type to make shopping lists, or they would have been here. As it is, we are treated to the dismal spectacle of a fridge covered in signatures that used to stand in one of his galleries, presented in a careful vitrine as if it were a holy shrine.

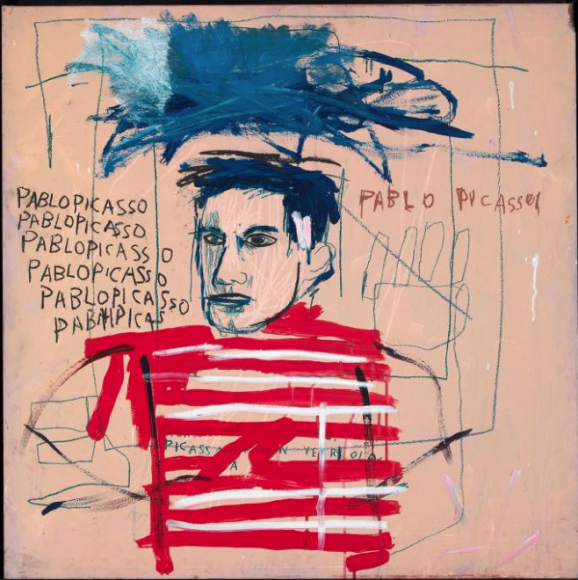

When the art does finally become tangible in this blizzard of bits, it is essentially a case of opening a tap and seeing what flows. Interested in sport, jazz, anatomy, cinema — the show has a documentary section filled with his books — Basquiat would absorb fragments of information from myriad sources and then regurgitate them in furiously improvised cascades of words, colour and cartoon imagery. Painted quickly with instantly drying acrylics, the torrents of stuff would be released with barely an organisational thought in an improvisational style learnt from the jazz greats he admired.

The energy involved in this haphazard creative process is always unmissable and occasionally effective. Having plastered his homemade canvases with references to baseball players, Renaissance artists, the stars of bebop, he would obliterate what lay below with grinning skulls that come increasingly to stand for him. It’s a solution employed too casually and too often. But the belief that everything that spewed out of him was art, and that his Haitian origins gave his imagery a voodoo power, is a glue that sometimes works.

If Basquiat hadn’t become an artist, he would have been a model, a rock star, a fashion designer. He had the looks, and this was the era when everything became interchangeable. Deep into the show, in another film, he’s being interviewed by Warhol, who had now become his artistic sugar daddy, and who sits with his arm around the giggling teenager in classic Jim’ll Fix It fashion and asks him the Warholian version of a profound question: “What’s your favourite colour?” It turns out to be blue. And there we have it. Basquiat’s most spectacular achievement, and it was indeed a telling one, was to bring the art world down to his level.

So, yes, I suppose that does make him “one of the most significant artists of the 20th century”.

Barbican Art Gallery, London EC2, until Jan 28