Allow me to start with a silly question: what are museums for? It’s a silly question because the answer seems so obvious: museums are there to collect things and show them to us, right?

Well, no, actually. That’s not right. From the beginning, back in the age of enlightenment, the task of Britain’s museums has been to improve us. They are an educative tool, 3D textbooks with visions and opinions, seeking to turn us into better people. With some museums — the British Museum, the Natural History Museum — this educative function remains obvious. But what about the Tate?

As a collection devoted to modern and contemporary art, the Tate has always had its work cut out when it comes to educating us. Show me a man who has had his mind improved by Carl Andre’s bricks and I will show you a Polish builder. Modern art is many things, and many of them are wondrous, but its past is too rebellious and its ambitions too inchoate for it to be an obvious conduit of knowledge.

Which is why the transformation of the Tate franchise in recent years into a cudgel of human improvement has been so noticeable. As its empire has grown, with outposts in Liverpool and Cornwall, and a nomadic Turner prize exhibition that flutters up and down Britain, the determination to turn us into a more enlightened modern society has grown more conspicuous.

The recent rehang of Tate Modern, which insisted that 50% of the exhibiting artists were women, had conspicuous sociopolitical ambitions. So too does Queer Britain, the survey of LGBT currents in British art that is now on show at Tate Britain. This year’s shortlist for the Turner Prize is a virtual Who’s Who of identity politics. And the Germany show that has opened at Tate Liverpool could not have been aimed more directly at all you misguided Brexiteers out there had it consisted of a photograph of Nigel Farage with a target on his forehead. The bigger the Tate becomes, the more determined it seems to be to act as a Panzer of national amelioration.

So an itchy part of me remains nervous that the reins being gripped here are the reins of right-on-ness, not the reins of art. That said, the Germany show is an excellent event, a two-part stab at foreign understanding in which both halves are useful and stirring.

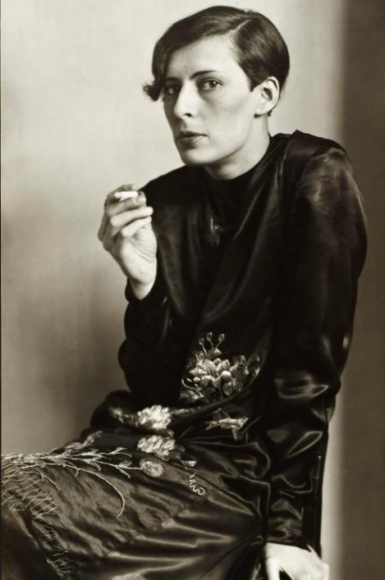

Part one looks back at the career of August Sander, a photographer whose celebrated gallery of portraits taken in Germany between the two world wars is habitually held up as a textbook example of “putting a face on history”. The portraits are part of a project called People of the Twentieth Century, which Sander commenced in 1900 and completed in 1950, though the focus here is on the years 1919 to 1945, or what we might term the Hitler years, unless we are in a pub in Essex on a Saturday night, when we might call them the Basil Fawlty years: the years we can’t forgive.

Sander grouped his sitters into “types” — farmers, workers, musicians, circus performers, artists, SS officers. Most are unnamed. It’s an arrangement that strikes a eugenic note and feels very German. The portraits are surrounded by a detailed timeline that unfolds along the wall and wants to provide a context. In fact, as if to prove that history doesn’t feel like history when it’s happening, the timeline and the faces seem curiously out of step.

Thus, in 1919, the year the Treaty of Versailles punished Germany for its role in the First World War by making it 13% smaller and giving away most of its natural resources, the Bauhaus school of art and design was also opened in Weimar, and Sander photographed a fellow with a huge forehead whom he classified as A Judge. Looking at the size of his forehead you assume this brainy chap must sit at the head of the supreme court or something. But no. He’s a boxing referee. Boxing was popular in Cologne, and boxing bouts need arbitration.

The grimness, the despair, the moral uncertainty that I assumed Sander would be recording in a nation with 1m new orphans and 600,000 new widows are surprisingly slow to show themselves. In 1925, the year Hitler published Mein Kampf, Alban Berg’s Wozzeck premiered in Berlin, the first nature preservation day was held in Munich and the Great Art Exhibition, devoted to expressionist and impressionist art, opened in Dusseldorf. Sander, meanwhile, was photographing artists who look like Hollywood actors dressed for the Oscars, and farmers togged up as precisely as lawyers.

Slowly, the darkness seeps in. Hairstyles grow more tousled. Clothes start to droop. The Teutonic crispness that is such a distinct feature of the show’s early stretches gives way to something messy and hopeless. Gypsies appear and strike a foreign note. Jewish faces loom up, looking resigned rather than defiant. In a section labelled The Last People, Idiots, the Sick, the Insane and the Dying, Sander photographs a heartbreaking gallery of kids in homes, blind people, invalids and tramps, while the timeline gets into step at last and records that Hitler signed an order that year authorising the killing of all Germans with physical and mental handicaps.

Torn out of the textbooks, made palpable by its evident humanity, it’s the story of a national mood growing rotten, like a crisp apple that turns to mush. The hatred of foreigners, the alienation from the rest of Europe, the nationalistic chest-beating — it all feels grotesquely familiar. And, just in case we’ve missed the connection with our own bedevilled present, the Tate ends its Sander show with a line of smiling faces photographed in 1945. The caption tells us they represent a type called The Foreign Worker.

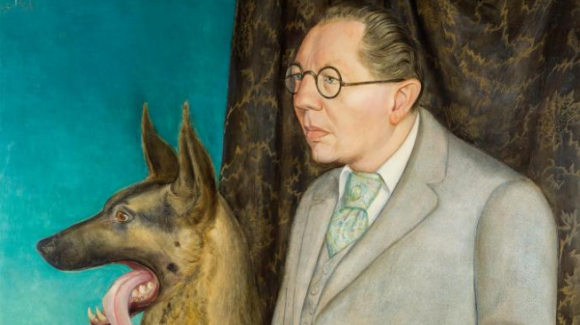

Part two of this rousing examination of Germany’s 20th-century past is devoted to the intense vision of Otto Dix (1891-1969). What Dix was isn’t easy to summarise. Sometimes he was a satirical painter, sometimes a realistic one. Sometimes he recorded his world in terrifying caricatures and sometimes in notably exact portraits. In an effort to give an overall shape to these fluctuating pictorial ambitions, the Tate presents him here as the possessor of the Evil Eye. And that will do for me as well. There’s a fierceness to the way he stares, a lip-smacking absence of compassion or empathy that’s more usually found in hyenas, wolverines and vultures.

Dix fought in the trenches in the First World War, and the prints he produced on his return are among the most bloodthirsty I have ever seen. Not even Goya was as savage as this. In 1922, when he takes up watercolour because he can’t afford oil paints, he makes this sedate medium snarl and spit in a set of sadomasochistic brothel interiors that see sex as a form of hatred.

Everything he looks at — women, rich industrialists, other artists, himself — seems to repulse him and cause his bile to rise. It’s a ghastly vision. And a brilliant one.

Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919-1933 at Tate Liverpool, until Oct 15