If I had to choose an Old Master to depict the Venice Biennale, I would, of course, choose Hieronymus Bosch. Only Bosch would have a hope of capturing the insanity, the turmoil, the crowds, the unexpected sights and that terrifying sense of a monstrous art world stomping all over the poor old island of Venice in an international effort to sink it. All biennales have something good in them. But all manage also to convince you that the end of civilisation is probably nigh.

This year’s effort, the 57th, is certainly no exception. Eighty-seven nations have descended upon La Serenissima to show off their modern art and bombard you with their issues. Three of them — Nigeria, Kiribati and Antigua and Barbuda — are here for the first time. But these fresh-faced beginners have been banished to the fringes. And, as always with the “Olympics of modern art”, it is the countries that threw their beach towels onto the sunbeds first — the old colonial powers — that have the best locations and the most lavish presence.

This is especially true of the main Biennale gardens, the Giardini, where the pavilions of Britain, France and Germany dominate the opening vista. At the 2015 Biennale, Britain was represented by the unclubbable Sarah Lucas, whose rude and chippy sculptures seemed to me to evoke perfectly the voice of the mouthy urban female: the girl on the checkout at Tesco. Not everyone was enamoured of her British working-class bite. So this year, in a huge respectability lurch, Vicky Pollard has been replaced by Miss Marple.

The venerable Phyllida Barlow, born in 1944, whose belated emergence has formed one of the most prominent storylines of recent British art, now occupies the British pavilion. Barlow makes art in what we might call the Blue Peter fashion. Digging into her collection of domestic and industrial waste — old cardboard boxes, toilet rolls, chicken wire — she transforms these humble materials into grand and colourful abstract sculpture.

As this is what she always does, I approached her Biennale contribution assuming it would be samey. To her credit, she has adapted the Blue Peter formula to this specific Venetian situation and created a junk installation called Folly that cleverly echoes the architecture and mood of the British pavilion. It’s charming, witty and better than I expected.

That said, as if to provide immediate proof that the 1950s are over, the German pavilion, next door, has a brilliant evocation of contemporary angst created by the multifaceted Anne Imhof. Using an amalgam of performance, sculpture, installation and sound art, Imhof plunges us into a grim modern reality of heightened security and robotic interaction. Her best touch is to lift you up onto a see-through Plexiglas floor, below which her unsmiling performers scamper like rats in a lab experiment. Some crawl. Some slide. Some pause to masturbate. Welcome to the human zoo, 2017.

Multifacetedness is a Biennale theme this year. Hardly anybody makes art in a straightforward manner. The French have a pavilion devoted to music, in which you can watch a squad of assorted instrumentalists recording one of those unlistenable records that have become an art-world speciality. The Danes, in what I hereby nominate as the worst contribution to the entire Biennale, incarcerate you in a black room for 30 minutes, where you listen to the rantings of Kirstine Roepstorff, instructing you to imagine you are a seed growing under the ground. I tried to leave after a couple of minutes, but they wouldn’t let me. Seeds, it seems, no longer enjoy any basic human rights.

Every Biennale has an overall theme chosen by its chief curator. On this occasion, Christine Macel, from the Centre Pompidou in Paris, has come up with a notion that initially gladdens the heart — Viva Arte Viva, which translates roughly as “long live art”. She is putting the exhibition in the hands of artists, she says, because they see the world better than others, and their vision should be celebrated.

The trouble is, having claimed to be celebrating artists, Macel sets about ignoring them in a Biennale effort dominated by long-winded curatorial explanations. What is it about French curators? Packing her show with dreary expositional essays that take a huge amount of space to say very little, Macel uses the occasion to mount a tiresome display of virtue signalling. If you’re an Inuit from northern Canada, you’re in. If you’re from London, you’re out.

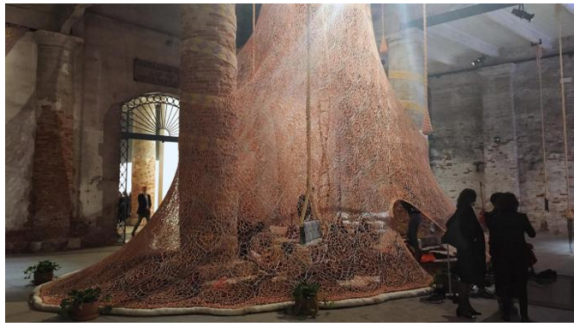

Split into nine “pavilions”, which are all meant to be different, but tend to feel the same, Macel’s Biennale show is a rambling mess studded with moments of extreme silliness. The first exhibit you encounter in the Pavilion of the Shamans is a large tent in which you can sit and play the maracas or strum a guitar. It has been created for us by Ernesto Neto, who has “adopted the form of the Cupixawa, a place of sociality, political meetings and spiritual ceremonies for the Huni Kuin Indians of the state of Acre in the Amazonian forest”.

Gap-year art parading a shallow knowledge of distant cultures is a Macel speciality. Magic and shamans are another. So is audience participation — that surefire way of getting visitors on your side. The Arsenale exhibition duly opens with a set of coloured boxes by Rasheed Araeen that visitors can rearrange into new patterns. Thus the big agenda-setting moment of Viva Arte Viva is a game of Lego.

I’m probably making it sound more fun than it is. Most of the exhibits in Macel’s event are chronically long-winded. When did art give up on the need to encapsulate? As the shows grow bigger, so do the sprawls. Even her captions are the length of a Lacan chapter. “Leonor Antunes invades the architectural surroundings, calling into question the modular elements of scale, size and volume, and examining the notions of repetition and duplication in the details of the surrounding space” is just the first sentence describing a profoundly dull display of glass lamps made in Murano.

Fortunately, Macel only has authority over her bits of the Biennale. Away from Viva Arte Viva, excellent displays of artistic freedom are happily continuing. At the Accademia, a superb display devoted to Philip Guston and the Poets reveals how important poetry was to Guston, and how it influenced his art. It’s worth going to Venice just to see the 50 Guston paintings that prove the point.

The American minimalist James Lee Byars was a fervent lover of Venice. Byars had a dream. He wanted to erect a golden tower, 20 metres tall, in the heart of the city. During his lifetime, it never happened. But now it has, and his gleaming golden phallus is currently playing magic games with the light on the edge of the Grand Canal.

Gold is another of the Biennale’s themes. A vast caratage of it pops up in all corners of Damien Hirst’s wonder-full spoof exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. It features prominently as well in the Scottish pavilion, where the impressive Rachel Maclean writes, performs, designs and displays world-class loopiness in a filmic fairy tale about fake news.

As if to prove you can make art that is politically engaged and a joy to experience, the Diaspora pavilion in the Palazzo Pisani features a squad of displaced artists from Britain, young and old, who have created one of the Biennale’s best events. Isaac Julien’s The Leopard is a beautiful film installation about the mysterious transport of black Africans to an ornate palace in Europe. Khadija Saye makes gorgeous wet collodion tintypes in which this haunting 19th-century photographic process heaps poetry and sadness onto her imagery.

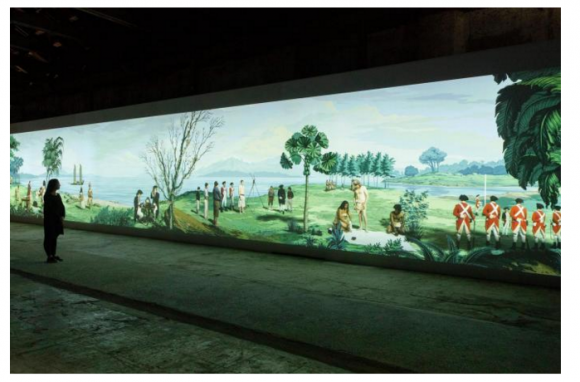

The best artwork at the Biennale? That will be Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus, in the New Zealand pavilion. This ambitious panorama, the length of a station platform, tells the story of Captain Cook’s arrival in the South Seas with a witty mix of live action and cunning special effects. Where most panoramas present a fixed viewpoint, this one moves and unfolds in a riveting animated sequence that took 10 years to complete and that deserves to be recognised as one of the key artworks of recent years.

The Venice Biennale continues until Nov 26