It has fallen to few great artists to live impressively long lives. Indeed, I can knock off the list for you right now — Titian, Michelangelo, Picasso, Hokusai. That’s it. These are the giants who got near to 90 or beyond. It’s one of the smallest and most illustrious clusters in art.

Some might be surprised to see Hokusai on my list. Not because you doubt he lived to his late eighties, but because you doubt he deserves to be known as a great artist. As a master of Japanese prints, the best known such master, he was certainly an achiever, but can he really be compared to Michelangelo or Picasso? Is being a master of Japanese prints enough?

The answer to all the above is yes, as a thunderous display that has burst through the doors of the British Museum makes abundantly clear. Not only was Hokusai the master of Japanese prints, he was a master of a quiver of other weapons. His drawing hand was preternaturally brilliant. His beliefs were fierce and transformative. His vision was strange and individual. And the fact that he lived to be 89 not only gave him a long opportunity to show off his range of talents, but became an issue for him: how to live in old age, how to keep achieving, how to grow better and better? Those are the worries that troubled the imagination of the marvellous old Hokusai (1760-1849).

The show commences with our hero in his sixties. Behind him is a career that is already long and successful. But he wants more. A lot more. As the helpful wall texts quoting chiefly from his letters put it: “At the age of 61 a person’s life cycle begins again.” At 60, Hokusai believed he was starting out. His most famous image, the Great Wave off Kanagawa, which you will have seen appended to a thousand fridges, wasn’t produced until c1831, when he was in his seventies.

The BM says it is focusing on his late work because something tangible happened to his vision when he turned 60. We might think of it as an upping of the flavours: a concentration. Until then, he had been an artist of enormous talent, but not yet the visionary he became. It’s a suggestion the show seeks to solidify with a quick up-sum: a tiny selection of pictures from earlier in his career that tries to encapsulate his achievements so far.

This up-sum is very nearly a bad idea. It’s so immediately impressive that all it actually makes clear is that Hokusai was always good. A gorgeous image painted on silk of a young woman combing her hair, what’s known in Japanese art as a Beautiful Woman painting, is made special by the exquisite sweeping line of her kimono and the sense of snaking movement it creates. If pictures made noises, this one would rustle, rustle, rustle with the sensuous whispers of shifting silk.

Having got our lymph flowing with this delightful amuse-bouche, the show settles into a detailed examination of Hokusai’s later work. At an age when most of us would be redrafting our wills, he saw himself as beginning. And although there are all sorts of exciting aesthetic reasons to admire the display ahead, there is also real social benefit to be gained, I suggest, from understanding old age in the Hokusai manner: as an epoch of new achievements when all that you produce is infused with all that you have learnt.

Interestingly, he was one of the first Japanese artists to have a working knowledge of European art. Commissioned by the Dutch East India Company in 1822 to produce a series of scenes of everyday life, he responded with a group of inventive paintings made notable by their use of deep European perspective. A jolly street scene of a samurai celebrating the new year features two very un-Japanese dogs sniffing each other’s bums in the foreground and a very un-Japanese street at the back, plunging into the distance.

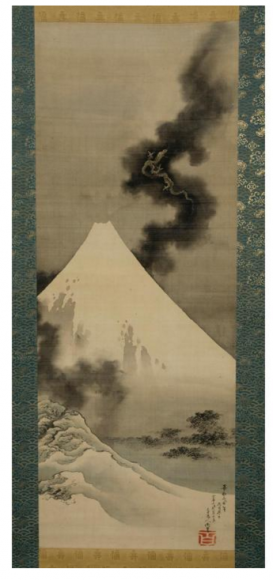

The bigger influence of European perspective is felt also in his most celebrated achievement: Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. It is here, among the massively inventive spottings of Fuji from all points of the compass, that the giant wave off Kanagawa dwarfs the tiny snow-capped triangle poking up on the horizon. The daring perspective, influenced by European examples, is certainly new and notable. But what really gives the image its power is the size and thrust of the great tsunami, and the remarkable freedom of the marks with which Hokusai describes its rage. His career-long empathy with wild and furious moments of nature — with winds, currents, torrents, storms, waves — is positively Leonardo-esque. And, as the show makes obvious, it has something spiritual at its core. So it grows with age.

That is why even in something as seemingly tranquil as his views of flowers in blossom, the most compelling image describes a clump of poppies bent double by the wind, twisting across the picture from right to left like an unfortunate combover lifted by a sudden gust. For the old Hokusai, nature is never still. It’s always restless. Always on the move to the next cycle.

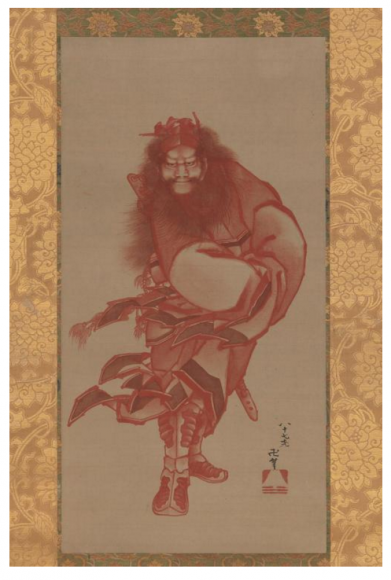

Back at the start of the show, the opening wall text informs us that he wasn’t always Hokusai. He liked to change himself, and managed during his career to assume more than 30 different artistic identities! So he was also Shunro, Sori, Taito, Manji, Iitsu, and only became Hokusai in 1798. Hokusai means “north studio”, and he chose the name as a tribute to the North Star, the one fixed point in the heavens.

We also learn that he was a Nichiren Buddhist, and that there were profound religious reasons for this constant renewal. Even if this wasn’t spelt out to us in the exhibition signage, the art gathered here supplies constant evidence of the determined adoption of different personalities. Hide the labels and you’d think you were dealing with a dozen artists.

His landscapes you know about. They are the most celebrated in Japanese art. But the same artist who paints Fuji as a faraway pimple also gives us mysterious close-ups of watermelons and the knives that cut them. Sometimes he paints perfectly and minutely on silk over several days. Then he dashes off a passing samurai in minutes on a slip of rice paper.

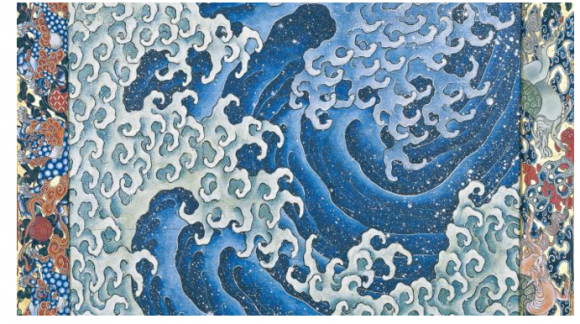

Although most of the art in the exhibition is on a scale that needs to be leant into to be enjoyed, he could be bold and dramatic, too, notably in a pair of remarkable ceiling panels, created when he was in his eighties, in which he zooms into the crashing surface of another huge wave and turns it into a constellation of twinkling stars.

When you’re this old, and this brilliant, you can see with perfectly clarity how the micro is also the macro.

Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave, British Museum, London WC1, until Aug 13