When you have been opining about art for as long as I have, most of the issues that speckle the territory have had occasion to be rehearsed. Floaty positions have been pegged down. Suspicions solidified. But there is one issue about which I have never been able to decide. To put it crudely: can bad people make good art?

Intellectually, it’s not much of a conundrum. Art is one thing. Bad people are another thing. The two should not be yoked together in a false equation. But art has never been an arena in which intellectual positions must be supported. It’s an arena that privileges the senses and the emotions. And in that foggy stadium, the question of good and bad humanity receives conflicting answers.

Take Caravaggio. He was a murderer. But his art has such enormous power and depth, carries so much religious conviction, that the darkness of its creator feels irrelevant.

On the other hand, the fact that Emil Nolde was a card-carrying Nazi and supporter of Hitler seems to me to invalidate his expressionism. If you are both an expressionist and a Nazi, what can you be expressing of true value?

These, then, are muddy waters. And the muddiest they have ever been was in the aftermath of the publication in 1989 of Fiona MacCarthy’s account of the evil and perverse life of Eric Gill. Before the release of MacCarthy’s biography, it was possible to see Gill as a charmingly deluded Catholic apologist, a belated medieval craftsman whom time had dumped in the wrong half-millennium. But once we learnt of his abuse of his daughters, the recurrent perversion of his sexual experiments, the penetration of his dog, for heaven’s sake, it became impossible to forgive his art.

Whenever I walked under his statuary on the way to meetings with the BBC at Broadcasting House, or encountered one of his pseudo-medieval sculptures in a nave or a churchyard, an unbeckoned sensation of aesthetic revulsion would rise up in my hinterland. How could anybody as monstrous as Gill make art as sweetly pious as this?

How brave, therefore, of Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, in Sussex, to devote an exhibition to exactly this question: how does the biography of Gill colour the way we view his art and, in particular, his treatment of the human figure? Bringing together 80 or so sculptures, drawings and wood engravings, this spunky show seeks to draw a cultural line in the sand beyond which Gill’s art can once again be observed with pleasure.

Ditchling was where Gill moved in 1906. With a duck pond, a church, a pub and a sweet museum arranged around the green, it’s an exceptionally pretty English village with, of course, something of Midsomer Murders about it. You suspect the local Barnaby is being kept busy by retired archaeologists and the fete organisers. It’s also where Gill founded an artistic community devoted to handmade arts, where he converted to Catholicism and where he abused his daughters.

The show commences with a brief reminder of the creative mood here at the time of Gill’s residency. There were weavers and carvers, letter-cutters and sculptors, printers and painters, all working together to revive English arts and crafts, and seeking also to blur the divide between them.

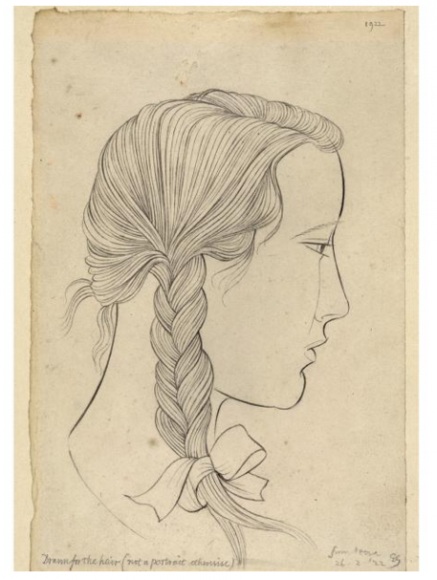

Gill was the driving force behind all that. He began as a letter-cutter and had no formal training in sculpture. Coming to art from lettering, he had an instinctive fondness for precise lines. Even when he took up figure-carving, it’s the lines and the incisions that impress, not the poses and the volumes.

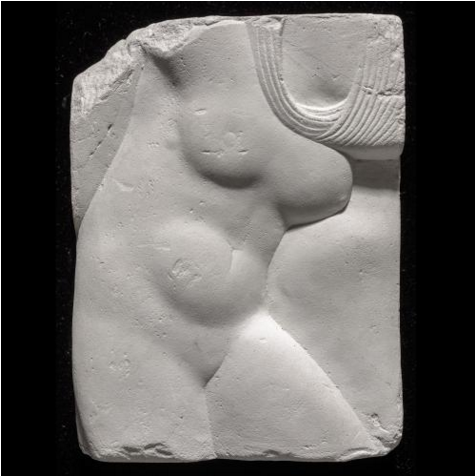

His first sculpture was a female nude created expressly, the show reveals, to plug a sexual gap caused by his wife’s pregnancy. His wife wasn’t available, so he carved something that was. It’s a revelation that fires a crack of warning into the gentle Ditchling air. Here was an arts and crafts pioneer who was suffering also from statuephilia. Even the small wooden “doll” he carved for his daughter Petra, one of the abused, is largely featureless except for its prominent pudenda.

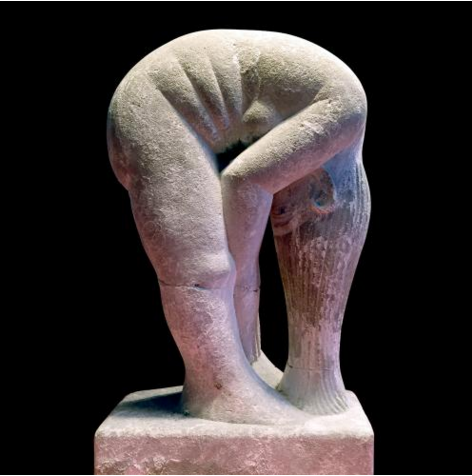

Another section deals with Gill’s fascination with female hair. This is where the largest of the exhibition’s sculptures form a harem of elfin nudes whose cascading tresses allow him to show off his undoubted prowess as an incisor of elegant lines. One nude is bending over, so her Rapunzel locks fall to the ground in a waterfall. Another has a mandala of beautiful hair framing her face. All have something of the pagan idol about them, as if their appearance is being worshipped rather than recorded.

Sulking in a nearby vitrine, meanwhile, is a creepy list written by Gill in which he records the dimensions of his abused daughters as they are growing up — their height, waist, bust — and compares them with his own. In the final line, he adds the length of his penis, flaccid and erect.

So this is not a show that avoids the problems. On the contrary, it addresses them with spectacular determination. There’s even a secret chamber of sorts, preceded by a public warning sign, in which Gill’s most explicit sexual imagery has been gathered. Most of it has religious origins and features enhaloed couples acting out a Catholic Kama Sutra of adventurous positions.

Gill apologists — they exist! — will have us believe that this creepy Catholic porn argues for a union of the spiritual and the physical, and that it’s a position that can be traced back to the philosophical ruminations of Thomas Aquinas. Perhaps. But it seems much more probable to me that Gill was a heartless pervert who sought ideological permission from the teachings of the church fathers for behaviour that would otherwise be unforgivable.

That said, in the end, it is not the false “spirituality” of his religious imagery, or even our prior knowledge of his wickedness, that invalidates his art. In the end, what really disappoints is the twee and milky falseness of his vision of womanhood: the recurrent sense here that the disrobed madonnas do not contain a single drop of tangible humanity. Instead, a dubious pre-Raphaelite fantasy is being given an art deco makeover.

To go back to our original argument, it is not Gill’s badness as a man that limits his achievement. It’s his badness as an artist.

Eric Gill: The Body, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, until Sept 3